Reflections on the theme of the ‘Embracing the Asian Century’ issue of Landscape Architecture Australia reveal that my practice as a landscape architect in Australia has paralleled, over a professional lifetime, the development of Australia’s relationship with the Asian region, both culturally and economically.

As the introduction to that issue outlines, the 1970s and the Whitlam Government saw a reorientation of national focus – away from the previously dominant relationships with the United Kingdom and Europe and toward our relationship with Asia. This reorientation was to directly impact the practice of landscape architecture from the start, as Australian landscape architects worked as part of multidisciplinary teams to spearhead the way – tasked with delivering a round of bold new Australian embassies in countries where previously, Australian representation had been much more modest. These new embassies were to have an overtly symbolic role and support Australia’s new diplomatic and cultural agenda.

Most of the first wave of homegrown and fully qualified landscape architects to practise in Australia in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly those who taught or led government-based teams, had qualified at a higher degree level in the United Kingdom and North America. They included Malcolm Bunzli and George Williams in Queensland, Beryl Mann and Grace Fraser in Victoria, Lindsay Robertson and Finn Thorvaldson in New South Wales, and Richard (Dick) Clough and Margaret Hendry in Canberra. Roger Johnson (Canberra CAE) and Peter Spooner (UNSW), both from the UK, were the leaders in the educational field at the time. The practitioners who were empowered by the Whitlam agenda often positioned their practice to contrast with those who had been formally educated in the UK. Responding to the mood of the times, they brought a new and distinctly nationalistic (and post-colonial) flavour to their work and actively promoted the idea of landscape planning and design that was more overtly rooted in the idea of Australia as place. Their designs explored and expressed an emerging sense of what identity meant in landscape design, an approach that underpinned their work not only nationally, but also internationally.

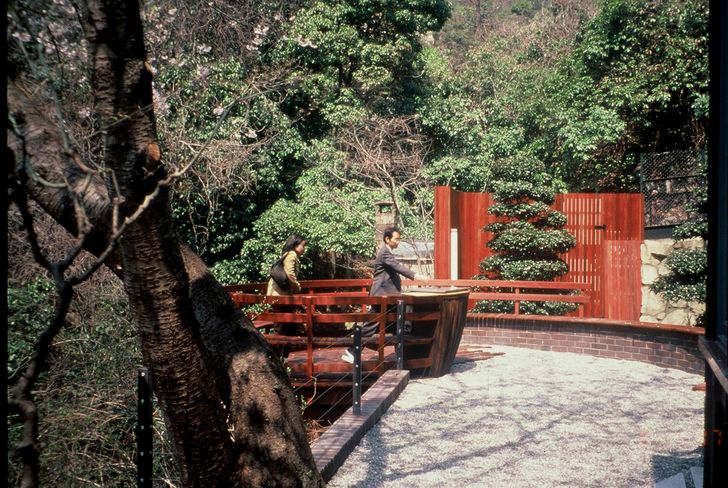

The landscape design for the embassy referenced local Thai culture selectively, using the urban waterway and massive tropical trees as inspiration but resisting the fussier traditions of local Thai garden design.

Image: John Gollings

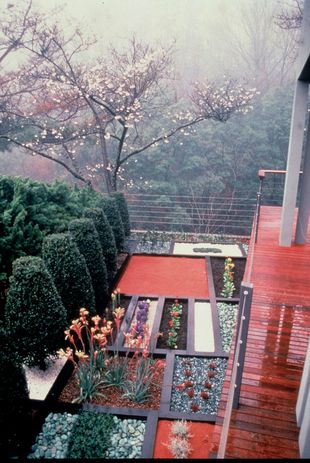

The Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Simon Taylor-designed garden for the Australian Consul General’s residence in Kobe, Japan, abstracts traditional Japanese garden design principles using Australian elements and materials.

Image: Stonehenge Homes and Simon Taylor

This trend is evident in the projects of Bruce Mackenzie, Adrian Pilton and to a lesser degree Geoff Sanderson, all of whom worked on Australian embassies across Asia and in the Middle East. While Whitlam had stepped onto Chinese soil to the tunes of overtly nationalistic folk songs, landscape architects and architects made designs that consciously or unconsciously expressed the interplay of contemporary cultural relationships and aspirations. Typically they questioned the degree to which each embassy should reflect either Australia or the host as a place or nation – individual or together? While the resulting work was as diverse and specific as the locations, it could be argued that most designers resisted overt references in their work and pursued a more nuanced form of expression. They sought to express, in physical form, an implicit (if optimistic) desire for harmonious political and cultural relationships. As a young project landscape architect in the mid-1970s I worked with Bruce Mackenzie and the example I know best is the Australian Embassy in Bangkok, where he and Ancher Mortlock and Woolley designed a project that aspired to express unity between the global and the local – a sensuous modernist building floated above a man-made curvilinear pond connecting with the local khlong (canal) network and was clad with glowing golden ochre tiles. The building and pond were sited to retain, quite contrary to local practice at that time, an enveloping canopy of the foliage of enormous existing figs and rain trees. These were underplanted with a minimalist palette of dark-green foliaged white flowers, the planting design again eschewing local practice, which mixed complex plantings of multicoloured foliage and floral tropical species. As befitted the overriding modernist approach, the landscape design referenced its local context and culture selectively, using the ever-present urban waterway and massive tropical trees as inspiration but resisting the fussier (and pervasive) traditions of local garden design. As with all the Australian Embassy projects of the period, a complex mix of contextualism and restrained modernism ruled, interpreted and modified by Australian firms and the particular project design team. Perry Lethlean, of Taylor Cullity Lethlean (TCL) in his later work on the Australian Consul General’s residence in Japan (1999), applied this approach in his own way, combining the locally recognizable geometry of the typical Japanese lunch box as a structure to frame and present a precisely conceived and executed viewing garden, a landscape with a tempting “filling” of Australian and local plants.

The Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Simon Taylor-designed garden for the Australian Consul General’s residence in Kobe, Japan, abstracts traditional Japanese garden design principles using Australian elements and materials.

Image: Stonehenge Homes and Simon Taylor

In the later 1980s and early 1990s Australian firms built on their initial experiences of these projects in the Asian region to explore other, more commercial, opportunities. From Melbourne, at the well-established planning and architectural firm Yuncken Freeman, Robin Edmond (by this time a landscape architect and architect with a real capacity for project initiation and coordination) teamed up with Noel Corkery (now in Sydney) and eventually me, to take advantage of the large-scale public and private works underway in rapidly urbanizing Hong Kong, before the territory was returned from Britain to China at the end of that decade. The local professional competition was primarily from well-established clients and consultants from the United Kingdom. This set up an interesting tension in the emerging postcolonial period as Australian engineers, planners, architects and landscape architects aggressively took on the established professional networks in open and sometimes fierce competition. Not only did they bring new energy, but they also brought new approaches to the challenges that resulted from rapid mass urbanization in tropical and monsoonal climates. They imported supporting specialist expertise from Australia and the USA (including Steve Calhoun and Rodney Wulff from Tract Consultants, and Geoff Sanderson, then from Gurner Sanderson). Their work created the basis for local landscape architectural and architectural professions that continued their work into China as it opened up, as well as other regions.

The recognizable geometry of the typical Japanese lunch box (bento box) frames a display of local and Australian plants.

Image: Stonehenge Homes and Simon Taylor

Review of these Hong Kong projects some decades later reveals a bold approach to urban structure and landscape that included moves toward what would now be characterized as urban design, including integration of “liveable” streets and squares along with the full range of recreational opportunities in landscape design at a neighbourhood scale. The scale of infrastructure, the steep, unstable topography and high-density rapid development meant that landscape architects and architects were involved in the full range of projects underway and were able to pioneer many new siting and stabilization techniques that have since become ubiquitous. Power-line corridors, tunnels, garbage tips, fun parks, high-density residential towns in the New Territories, full-scale urban parks, inner-city squares – the full gamut. Such experiences in planning, site planning, design and delivery of diverse and complex projects increased the capacity of Australian landscape architects to work across complex domains, cultural, ethnic and professional. They formed working associations with diverse mixes of planners, engineers, architects and clients and to do the work more effectively, employed professionals from across the globe and from local universities and firms.

From these early forays, the Australian landscape architectural profession developed and diversified, with many more than a few pioneers now working across the region. In addition to larger firms such as Hassell, Tract Consultants, McGregor Coxall and Aspect Studios, individual landscape architects are also sourced to contribute their particular specializations in habitat planning and restoration for endangered species, advanced horticultural and cultural knowledge. They work at every level.

In education, Australian graduate programs in landscape architecture – at master and doctoral levels in particular – are in constant demand from across the entire Asian region, including Indonesia, India, Malaysia, Korea, Singapore and China, often outweighing domestic demand. Pursuing studies at the advanced levels, students want more than basic knowledge; as a result, graduate programs typically include international field trips and studios to expose students to cross-cultural working conditions like those they will experience in practice. Given the challenges that these young professionals will face in their work, through them our responsibilities to the Asian region continue. Internationalization poses particular challenges for landscape architectural educators, who must on a daily basis position their teaching for a diverse student cohort and reach beyond the profession’s roots in the Western traditions of science, design, construction and practice. To be prepared for a complex inter-cultural future, skilled practitioners in landscape architecture, wherever they are, now need to be prepared both culturally and socially and our educators are there to lay that foundation. The Australian profession of landscape architecture has always been tested beyond its shores. Hopefully this process will continue, in all its dimensions.

Source

Practice

Published online: 17 Jul 2018

Words:

Catherin Bull

Images:

John Gollings,

John Gollings,

Stonehenge Homes and Simon Taylor

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2018