Landscape Australia: Could you tell us about the design concept for the precinct?

Anthony Brookfield: We wanted to establish a precinct-wide approach to the design. It’s very much a city-making project and we really wanted to emphasize the Western Australianness of it, and to establish a strong sense of place and a connection to the natural environment. We also wanted to embed the scheme with a meaningful Indigenous layer – it was very important for us to acknowledge that this is Whadjuk land and a significant site that was used for ceremonies and burials. We wanted to tell those stories, and convey the importance of flora, fauna and landscape to Whadjuk culture.

LA: How did you approach translating Indigenous narratives into physical design elements?

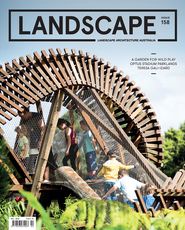

Hannah Galloway: We worked really closely and collaboratively with the Whadjuk Working Party – we talked through every aspect of the design with them. When we were designing the Chevron Parkland, we wanted to make it clear to the group that we wanted to represent their culture within that space. Working with [the party], we selected the six seasons as a way to express [aspects of] that culture. We looked at what traditionally in the Whadjuk culture, people would have been doing at certain times of the year in those seasons, and we [tried to] create a sense of that space or that element within the playground, using materiality and planting from that season. Each season is represented by a play zone.

AB: Elements within the play zone were developed either by ourselves or in collaboration with Form, which managed the involvement of the local Indigenous artists. LA — Collaboration and consultation has been a significant part of this project. Who else was involved?

HG: Unusually for a project of this size, Hassell was the lead consultant within the actual landscape precinct area, which was nice for a change because then it was a design-driven process rather than an engineer-driven process. We worked very collaboratively with the other engineers and specialists, particularly the civil engineers at BG&E, and Arup, which did the pedestrian modelling and traffic and access. Geotechnic was also very important because the site was so degenerated. There were a lot of user groups as well, who talked about what they wanted to see from a stadium with a precinct.

LA: It sounds like a lot of effort went into the design process.

AB: Four years.

LA: What are some of the narratives one might experience on a journey through the site?

AB: [We hope visitors will] start to get a sense of the Indigenous narrative entering the precinct, not just in the Chevron Parkland but also passing through the arbour on the south side of the stadium. There’s also that sense of landscape, which comes from being in a place that has extreme infrastructural demands placed on it, in terms of funnelling 60,000 people in and out. We’ve tried to integrate that aspect of the precinct as much as possible, with as many trees and as much planting as possible and create lots of respite spaces from the big stretches of openness – [contrasting] areas of scale and intimacy. Even in the design of the corrals in the eastern plaza through which people leave and enter – we didn’t want that to be experienced as if you were just funnelling sheep. There are lots of different “feels” to the landscape too – the northern landscape area, which is about rehabilitation and re-establishing habitat, feels quite natural, and is very different from the western lake and river, which is different again from the south side. We’ve tried to create a sense of richness in [the overall design] as well as seamlessness.

LA: Were there other narratives you wanted to reference?

HG: The curatorial theme was that we had the sport, the people and the land. The precinct and parklands became the land, the podium that the stadium sits upon, which is almost like a plinth, is the people, and the stadium itself is the sport. We didn’t necessarily want to move away from those. [We wanted to make the precinct] about the land and the original people, the Whadjuk people and the Whadjuk land.

LA: The stadium is a contemporary piece of infrastructure: Is the use of technology continued in the design of the landscape?

HG: There is a degree of [technology] in terms of how the operator wishes to run the stadium. We’ve given them the structure and ability to do so. There are wayfinding totems across the site, each of which has wifi, and a large digital screen. We’ve got service bollards, with communications and electricity and water, so the operator can run any event they choose to imagine. We’ve tried to create an adaptable space for the entire community.

Credits

- Project

- Optus Stadium parklands

- Design practice

- Hassell

Australia

- Project Team

- Anthony Brookfield, Sarah Gaikhorst, Hannah Galloway, Douglas Pott, Aysen Jenkins, Hannah Pannell, Nicholas Pearson, Jill Turpin,

- Design practice

-

Cox Architecture

Australia

- Design practice

-

HKS

- Consultants

-

Access and maintenance consultant

Altura

BCA and universal access consultant John Massey Group

Electrical engineer Wood and Grieves Engineers

Hydraulic engineer SPP Group

Lighting Philips Lighting

Public art consultants Form

Structural and civil engineering BG&E

Traffic engineers Arup

Waste management consultant Encycle

Wayfinding Büro North

Wind Engineering CPP

- Site Details

-

Site type

Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2018

Design, documentation 40 months

Construction 36 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Parks, Playgrounds, Public / civic, Sport, Tourism

- Client

-

Client name

Government of Western Australia

Website Government of Western Australia

Source

Practice

Published online: 24 Sep 2018

Words:

LandscapeAustralia Editorial Desk

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018