Sydney Park is a landscape of the Anthropocene. Its creation is the story of the transformation of a “bleak and forbidding” site with “the appearance of a moonscape or post-nuclear terrain” to a biodiversity hotspot.1 Located in the Sydney suburb of St Peters on a former brickworks and landfill, the park is today distinguished by remnant brick kilns and their chimneys, a series of large grassy mounds, a chain of ponds and bands of planting, all of which imbue the site with a picturesque and deceptively natural aesthetic. However, this park is a highly constructed landscape.

Sydney Park, which covers just over forty hectares, is also fundamentally an ongoing urban project, a manifestation of Sydney’s ongoing efforts to wrest best value from its landscape. Since its official opening in February 1991, three years late and incomplete, the park has evolved in three distinct phases. These phases demonstrate characteristics of resilient systems, each an episode of reorganization, development, consolidation, and expansion. Each phase speaks to park design as a form of experimentation, where failures become learning opportunities.

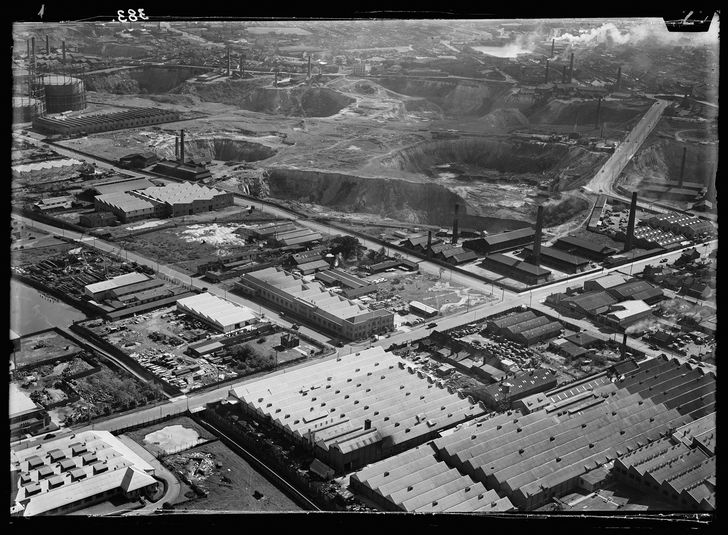

The site of Sydney Park was subjected to a century of intense clay extraction before its transformation into a biodiversity hotspot.

Image: courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales, FL 8805329

Sydney Park’s first phase, overseen by the NSW Environment and Planning Department and South Sydney City council, focused necessarily on literally re-establishing the ground for the park. Two early masterplans for Sydney Park (by Conybeare Morrison and Partners (1982) and Land Systems EBC (1989)) proposed four key moves: reform the site as an urban retreat with grassy mounds as “sentinels;” re-instate Sydney’s regional vegetation communities within the park; focus pedestrian circulation at the perimeter; and direct run-off into constructed ponds extending from the centre of the site to its southeast corner. An absence of playing fields marked its difference from local parks.

The second phase began shortly after the 1991 opening, when the state government transferred responsibility for the park to South Sydney City council. This was largely a phase of developing the site and reckoning with site conditions, the first task was to finish the park – at the time only the northern edge and south-east corner of the park were complete. As the new landforms and ponds settled, challenges became manifest. Topsoil was thin and infertile, leachate burbled at the surface and many trees died or grew stunted. Despite these persistent challenges, cultural identity and an attachment to the park by the community were established, particularly through community tree plantings, various festivals and the adoption of the brick kiln chimneys as the logo for South Sydney City council.

A third phase of consolidation followed the merger of South Sydney City Council with the City of Sydney in 2004. A large, well-resourced council, the City of Sydney placed Sydney Park high on its sustainable global city agenda and featured the park as a prominent green “hub” in several strategic plans. Major projects followed the merger, including a detailed masterplan in 2006. Prepared by Aspect Studios, this plan retained the concept of urban retreat and the programmatic distinction from smaller parks, but also amended soil profiles and planting elements to improve social and ecological diversity within the upgraded park. The city also implemented a water re-use scheme in the park, with Turf Design Studio and Environmental Partnership as the lead designers. This scheme, known as the Sydney Park Water Re-use Project, has to date won thirty-four local and international awards, making it one of the – if not the most – highly awarded landscape projects in Australia.2

Today Sydney Park demonstrates the technical and creative potential of landscape architecture to recalibrate city-nature relations, but caution is needed. The park may be entering a fourth phase. The NSW Environment Protection Authority recently declared Sydney Park contaminated, and thus confirmed the persistent risks of reconstructing anything from or upon former industrial sites. Development pressures in the area are relentless, with several new projects underway along the edges of the site. A 400-unit multi-million-dollar mixed-use complex, One Sydney Park, is set to rise within the park’s eastern perimeter. This will most certainly put eyes on the park, but it may also blur the distinction between public and private, and escalate real estate values. The WestConnex motorway is being carved along the southern and eastern edges of the park, along with a landbridge, playing fields and a pool. Will this be an opportunity to expand the park as an exemplar of green infrastructure or will it erode the park’s integrity?

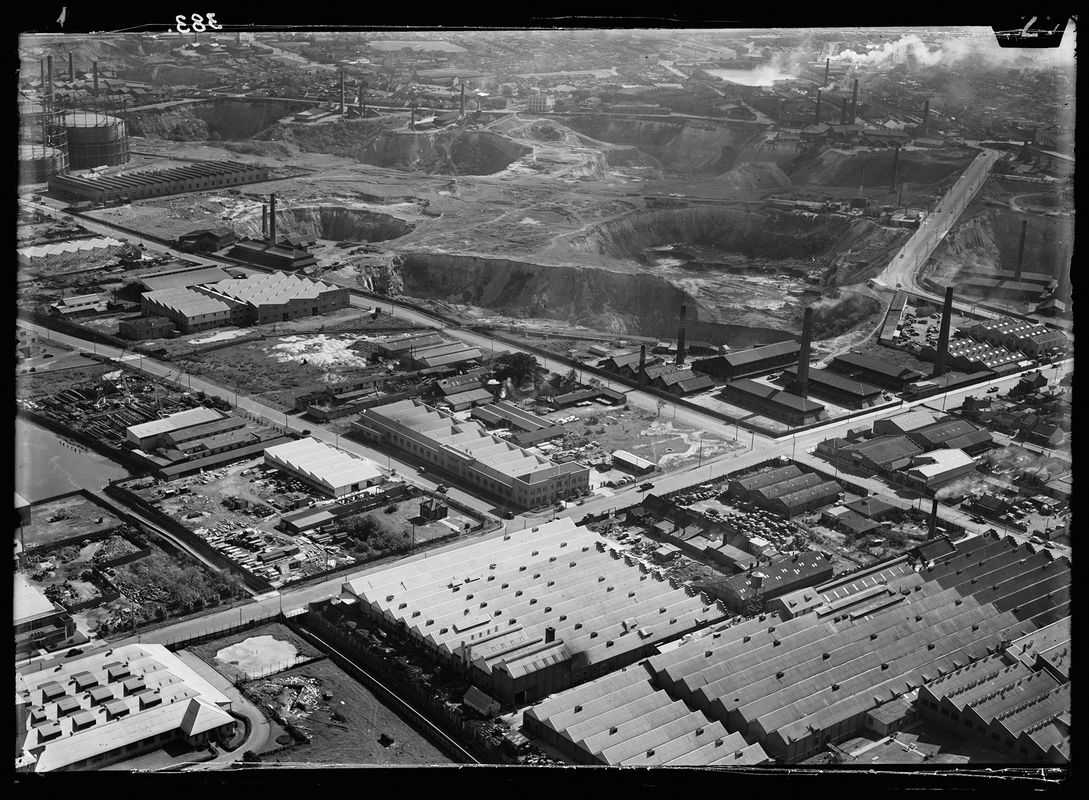

With development accelerating around the edges of the site, there is a chance to foster new relationships between park and city.

Image: Ethan Rohloff

At the moment, Sydney Park is a good news story of the Anthropocene. Following a century of intense clay extraction and a short period of landfilling, in an even shorter period – less than thirty years – we humans constructed a new and very urban ecosystem out of a profoundly disturbed site. In the brief history of Sydney Park, much has been learned, mostly through trial and error, in particular about the challenges of site conditions on landfill. These lessons may seem elementary today, but there were few precedents in the 1980s and early 1990s. The B horizon (subsoil) is crucial to soil and plant health. Methane production is unpredictable but persistent. Strategic and restrained programming of activity works. Creating ecosystems creates a framework for cultivating stewardship.

If today Sydney Park is ecologically and socially rich, it is also more interconnected with broader urban systems. The park, in turn, works hard for the city, with the acclaimed water re-use scheme exemplifying the range, variety and extent of work that parks can do for their cities.

In the future, if the scheme expands as planned to supply the surrounding precinct, it will create new dependencies between park and the city, and between nature and humans. At the same time, the emerging projects on the park edges are already testing the resilience of the park’s structure and systems. In doing so, these projects also underscore the imperative to engage with the park – indeed all parks – as ongoing, open-ended experiments in city-nature relations.

1. Leo Schofield, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 December 1988, p.40; City of Sydney, Urban Ecology Strategic Action Plan, 2014.

2. Turf Design Studio, personal communication, 2019.

Source

Review

Published online: 22 Jun 2020

Words:

Catherine Evans

Images:

Ethan Rohloff,

courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales, FL 8805329

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020