As Australia’s first fully-realized linear park, comprehensively integrating environmental, recreational and economic objectives, Adelaide’s River Torrens Linear Park was groundbreaking. Concept designs for the more-than-500-hectare park that winds through Adelaide city and its suburbs were prepared in the 1970s, offering a coordinated vision for a park that embraced and connected the varying ecologies, functions and character of the river’s landscape. The project’s ambition was to provide a flexible framework, governed by a central authority, that would guide the development and maintenance of a future park.

The Karrawirra pari (“Red Gum Forest River”) has been revered by the Kaurna people, the Traditional Custodians of the Adelaide Plains, from time immemorial – its rhythms shape their social, economic and spiritual world1. Within a few years of European occupation however, the natural river – a fragile yet turbulent system of seasonal flows – was devastated2. The river was a primary influence on Adelaide’s location and settlement pattern, however its original form was destroyed in pursuit of recreating the aesthetics of a romanticized English river and its required function as an industrialized water source and drain. Tensions between these conflicting roles intensified as the twentieth century city encroached upon the river – and the river intermittently retaliated by flooding.

In the seventies, the requirements for flood mitigation and stormwater management, paired with a budding appreciation of the benefits of open space, resulted in the creation of Adelaide’s Linear Park and Flood Mitigation Scheme,3 developed as a joint venture between the state government and twelve councils. Hassell (known as Hassell and Partners and then Land Systems across the lifespan of the project) played a lead role throughout, producing the River Torrens Study: A Coordinated Development Scheme in 1979 and continuing with the development of the management framework and detailed design of projects along the river for the following two decades.

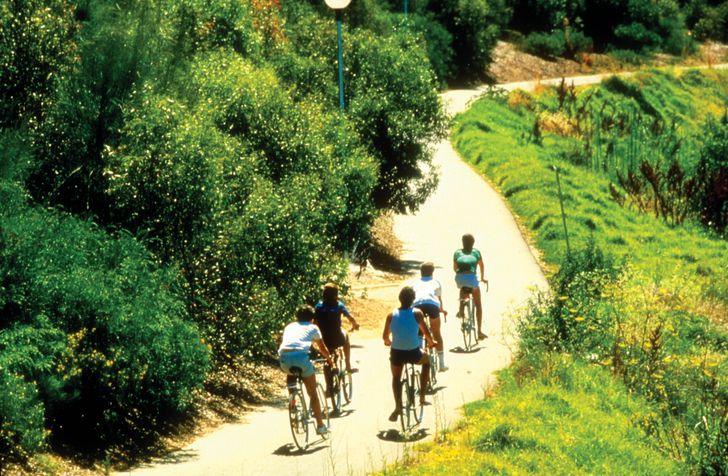

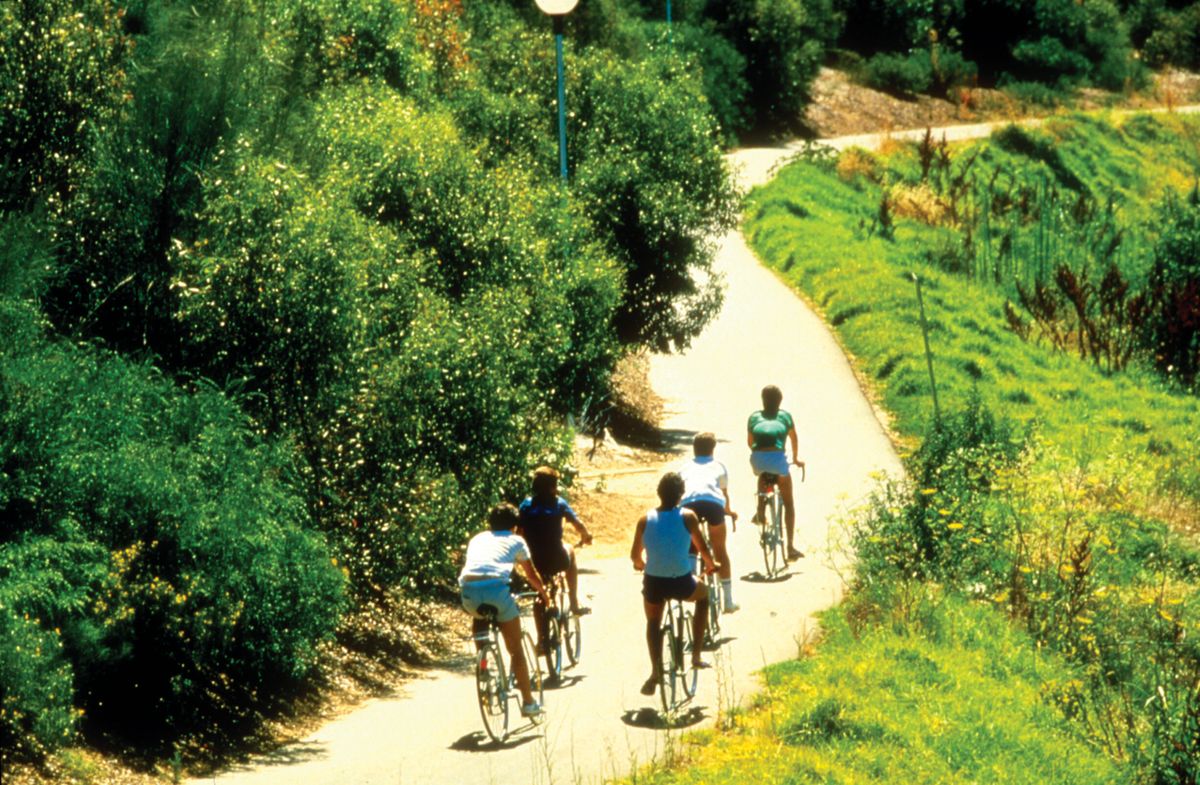

Cyclists wind along the river’s edge on the park’s shared path, circa 1980s.

Image: courtesy Hassell

By the end of the nineties, this comprehensive and design-led approach, realized on the ground, had heralded social, environmental, economic and recreational benefits, alongside extensive hydrological adaptations. Intensive weed eradication and revegetation strategies aimed to regenerate the river’s biodiversity, and previously fragmented uses and ecologies were linked by re-establishing the once dominant canopy of river red gums. Yet, environmental regeneration efforts were thwarted by influences beyond the project team’s control. Of these, the most significant were the river’s challenging edge conditions and enduring hard-infrastructure adaptations, and unrelenting external inputs, including pollution and stormwater run-off. Nevertheless, the designers persistently highlighted the need for sensitive and sustained maintenance in realizing the park’s full potential.

Today, River Torrens Linear Park is popularly experienced in motion, by bike or foot. The park’s many and varied activity nodes are connected by a path network that runs the full thirty-two-kilometre park length and supports diverse landscape experiences. Views of sylvan valleys in the Adelaide foothills contrast with the sights, sounds and smells of industry to the west of the city, evoking an appreciation for the progress of environmental protection and hinting towards the necessity of continued improvements. Toward the final concrete culvert that channels the river to a rather undignified end, direct interaction with the river bank is restricted to horses and their riders. It is an unusual remnant pastoral scene, so close to the city – and an abrupt contrast to the adjoining, more recently revitalized Breakout Creek wetlands. Such varied landscape experiences offer diverse recreational opportunities as well as physical and social connections. Yet, further enhancement of the park as an integrated system of hills-to-sea ecologies is currently being hampered by its escalating and diversifying use, and decades of inconsistent management.

Hassell’s proposal in their 1979 scheme to create a new controlling body with decision making and regulatory powers to ensure the longevity of governance and maintenance along the river corridor was not pursued. In fact, even the River Torrens Committee that catalysed the project was disbanded upon the commencement of the park’s construction in 1982. Over the decades,

the river and park have been subject to numerous unclear governance models and disconnected maintenance and renewal strategies, applied by a range of governing bodies. The ambition of the coordinated and connected river corridor has been watered down and degraded over time. More recent restorative efforts aimed at combating rubbish and managing blue-green algae and invasive carp species have targeted the symptoms rather than the causes of ecological ill-health. There is an inability to see the forest for the proverbial trees.

Now, numerous stakeholders are requiring more of the park as a place of ecological, recreational and experiential value. Recent tensions include a focus on the city’s Riverbank Precinct, densifying inner suburbs, a hotter and drier climate with more severe weather events, and the rising understanding of biophilia. These considerations are straining the established nature of the park, intensifying requirements of, and tensions between, its multiple roles, and complicating efforts towards improvements.

O-Bahn Bus route through the River Torrens Linear Park in St Peters, 2019.

Image: Rebecca Connelly

The park’s influence on Adelaide has expanded, as has our understanding of river systems, including the River Torrens catchment and interaction with local tributaries. Recent AILA award-winning projects Felixstow Reserve Redevelopment4 and Adelaide Botanic Gardens Wetland5 revive and fortify the ecological processes of two of these tributaries, regenerating social, cultural and educational connections with the waterways. These projects also demonstrate landscape architecture’s heightened commitment to Reconciliation by seeking meaningful engagement with the local Kaurna people in the pursuit of integrated cultural and ecological systems. These outcomes are benchmarks when contemplating a unified future for the park, the Karrawirra pari and its catchment.

The importance of the River Torrens Linear Park calls for a revisiting and reinvestment in its original vision and a renewed commitment to the project’s ongoing legacy of broad public value. Landscape architects must lead a renewed twenty-first century whole-of-catchment approach to strengthen the park and its interconnected networks through sensitive redevelopment with sustained and coordinated maintenance. They must advocate for – and be a prominent voice in – re-establishing a comprehensive governance model for the park, to ensure one eye is kept on the forest, and the other on the red gum.

1. Sharyn Tate, The Creation of the Torrens: A History of Adelaide’s River to 1881, (Masters thesis), University of Adelaide, 2005, p.14

2. ibid.

3. Ted Dexter, “Adelaide Creates a Great Asset: River Torrens Linear Park,” Landscape Australia, vol 4, 1997, p.343-348

4. Felixstow Reserve Redevelopment by City of Norwood Payneham & St Peters, in association with Aspect Studios, Kaurna Nation Cultural Heritage Association, Paul Herzich, Oxigen and Integrated Heritage Services

5. Adelaide Botanic Gardens Wetland by TCL (Taylor Cullity Lethlean)

Source

Review

Published online: 29 Jun 2020

Words:

Rebecca Connelly

Images:

Rebecca Connelly,

courtesy Hassell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020