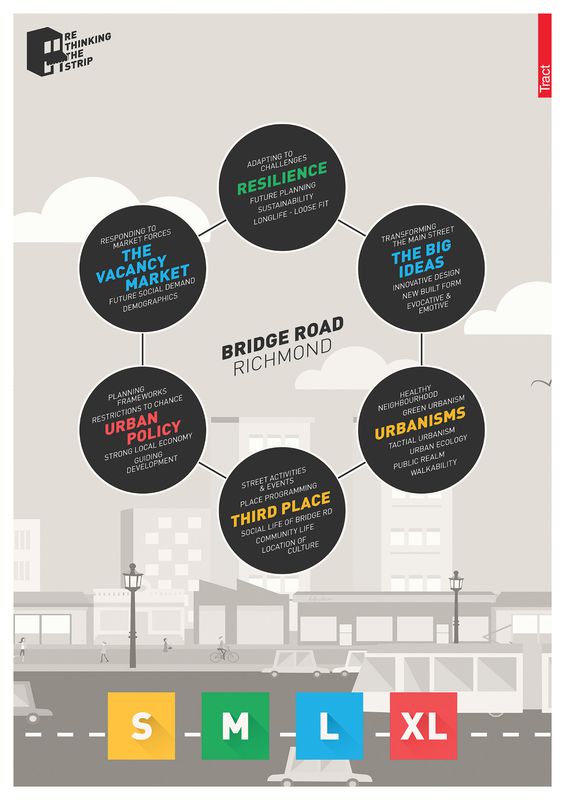

Tract Consultants’ Rethinking the Strip forum referenced the seminal book S, M, L, XL by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau.

Image: Tract Consultants

A combination of circumstance and great timing can illuminate previously unforeseen opportunities. For Tract Consultants directors Deiter Lim and Steve Calhoun, the light-bulb moment came over lunch with Professor Alan Pert, d irector of both Melbourne School of Design and Northern Office for Research and Design (NORD). NORD’s WASPS South Block project in Glasgow had recently received The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland’s prestigious Andrew Doolan Best Building in Scotland Award. It received this in part for the way it employed an unusual financial model to generate urban renewal: two floors of commercial space helped subsidize rents for artist studio spaces.

“ There was a trade off; it was an enormous building to convert on a shoe-string budget,” says Pert.

The smaller design budget was worth it. Where a developer-lead apartment conversion may have brought sixty new residents to the building, and no enticements to linger at street level, NORD’s solution brought 365 people into the building – all living, working and visiting around the clock. It was a much-needed injection of vitality.

Back in Melbourne, Tract Consultants staff had noticed an alarming increase in shop vacancies along their local strip – Bridge Road, Richmond – and had mapped out those vacancies as an internal exercise. The street, once popular as a fashion outlet-shopping destination, was suffering in the wake of the global financial crisis and changing consumer habits. The story of Pert’s studio complex in Glasgow triggered a conversation about how to generate ideas for urban renewal through finding alternative financial models and user groups. Together with Orlando Harrison, the practice’s senior principal of urban design, Calhoun and Lim decided to dedicate their biannual practice forum, due to be held in Melbourne, to Bridge Road, calling it “Rethinking the Strip.”

With enthusiastic support from the City of Yarra and Melbourne School of Design, Tract Consultants took on a vacant shop and transformed it into a pop-up studio/meeting place, in order to “live and breathe” the site. In turn, Pert created a multidisciplinary design studio at the Melbourne School of Design called “The Vacancy Market,” enabling the forum to be informed by the broader research the students gathered.

Framed around Rem Koolhaas’s “S, M, L, XL” ideas of scale, the forum was held over two days in October 2014. Tract Consultants staff, colleagues, relevant stakeholders, students and economists came together in the pop-up shop to flesh out the key issues and articulate a set of propositions to drive the conversation into the future.

In November 2014, Melbourne School of Design lead a follow-up forum as part of the “MTalks” series at MPavilion – Melbourne’s answer to London’s Serpentine Pavilion – in the Queen Victoria Memorial Gardens. Harrison, who represented Tract Consultants, said that the follow-up further broadened the conver sation they’d begun at Rethinking the Strip.

“We were able to debate the impact of social change on retail environments, and everything from the psychology of retail through to changing governments and changing policy,” he said.

Lucy Salt spoke to Deiter Lim and Orlando Harrison at their Melbourne office.

The forum brought together students from the MSD and staff from Tract Consultants to rethink the contemporary urban shopping strip.

Lucy Salt: As a private practice, where’s the value in facilitating these larger conversations, especially when they’re not part of a commissioned project?

Deiter Lim: All the previous forums were internal, where people would come and talk while staff listened and asked questions. So this time we said, “Let’s take it out and see what comes of it.” We chose to take it out on the street and open it up because … we’ve been here since 1982, we’ve seen it rise and fall … we’re part of the community … This is about actively generating a broader discussion; it means that everybody has a sense of collaboration around an important issue.

[ Typically, when] we get commissioned to do a streetscape, we say, “Okay, we need to change the paving, put some trees in, how are we best going to do it?” But the real problem is how to get more life on the street. So the experience of this forum enabled our staff to say, “Okay, I can put ten trees in the street and we can have an argument over the loss of one car parking space, or we can have a broader discussion about bigger ideas.”

LS: In a recent interview, you said, “Councils don’t want to think about enabling policy, they want to think in terms of regulating policy.” What do you mean by “enabling” versus “regulatory” approaches to policy-making?

DL: Councils want to enable, but to do so – and this is the problem with politics in general – it’s this concept of picking favourites and giving advantage to one over the other. Therefore, councils have to regulate. The City of Yarra would say, “We’d love to do all of this, but how can we ensure it is fair and equitable for everybody?” The council enabled us to do what we did by not regulating what we did. We couldn’t get a permit in time – we actually wouldn’t have got a permit, regardless, because [the project] didn’t meet the regulatory requirement for the zoning of that street. Enabling might be as simple as quietly getting out of the way, and saying, “It’s actually good for the strip.” Of course, you do need some level of regulation to ensure things don’t go too far one way.

LS: As designers you are solution oriented, so this idea of messy zoning, messy design and getting out of the way, can be tricky. At the end of the project did you notice a shift in your thinking?

Orlando Harrison: There were a lot of discussions around what you can do in design terms once you start parking some of those assumed regulatory barriers, and I say “assumed” because some of those barriers aren’t there, they’re just perceptions. There was beautiful friction between [professional ideas] and student ideas, which are freer, which sparked ideas about where to stretch the known limits. Part of that enabling by the council was it acknowledging that the process was the enabler in itself. By the end, the council was supportive of just having that conversation. It was so completely different from going through a structure plan or a streetscape masterplan or anything like that.

LS: Can landlords and developers be encouraged to invest in these kinds of ideas?

DL: I’ve had conversations around the forum topic with developers [who said] in the end, the market is the enabler. All of us in the profession are trying to ensure life on the street, but the converse argument from the developer was that “the market picks winners and losers. If you don’t want to be the winner and actually drop your rents, eventually the market will say, ‘Sorry, you’ve lost.’” Why are you now going to intervene to ensure the developer gets a return?

OH: [In this case] the local community could see the benefit of having a conversation with landlords and developers in order to find that mutual benefit – rather than the community saying, “We want open space and a lovely cafe,” and the landlord/developers saying, “Well, we want to develop something that makes us money and never the two shall meet.” We all know they do meet, but they don’t meet neatly when it’s just a regulatory process via a planning application. You don’t get all those interesting ideas that flow through somewhere in the middle. There was a session called The Third Place. People came up with wonderful ideas about what third places could and should be, but then who makes these things happen? Could an individual developer do it? Rarely. Is the council going to do it? Probably not. The one thing people wanted sat nowhere in the list of the way things usually happen.

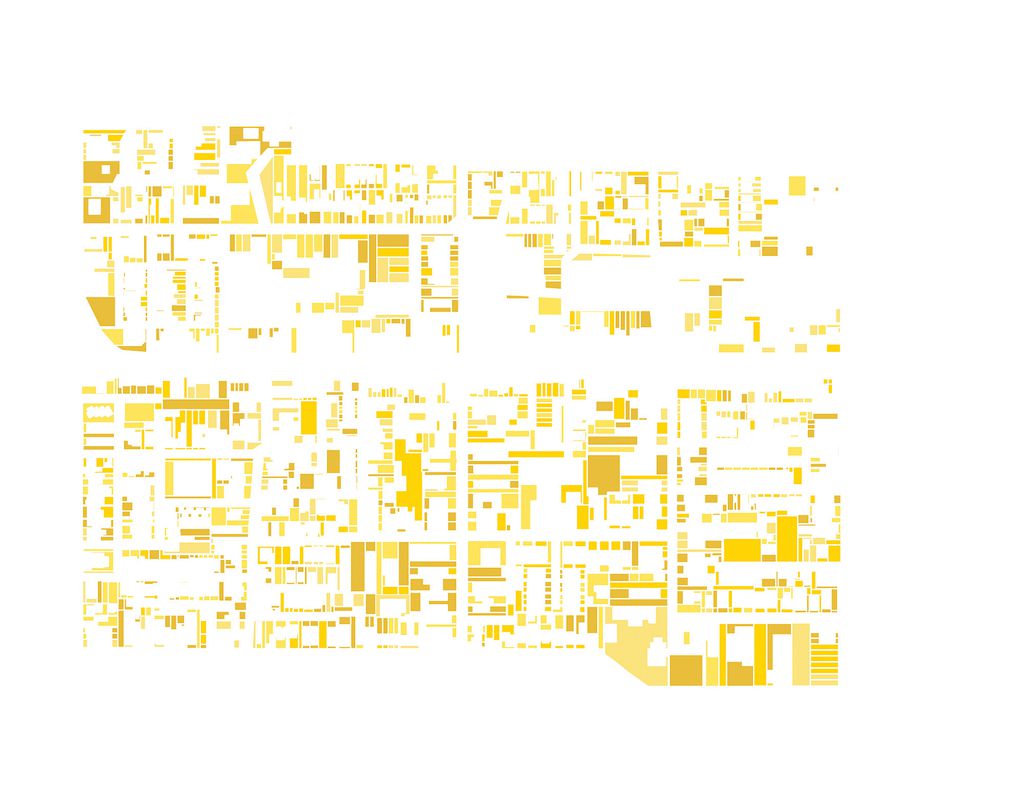

These diagrams explore issues of the small scale, and informal, in contrast to the linearity of the high street.

Image: Melbourne School of Design

LS: And perhaps just off the boundary of your specific project?

OH: Exactly – there’s the dashed line and that’s the project. Interestingly, with the student’s work, they had The Vacancy Market as their title, and they had Bridge Road as the site, and they all focused just off the back of Bridge Road.

LS: Is the concept of a third place more fascinating to students?

OH: Part of it is [a desire to] push boundaries. Designers intuitively want to do that anyway. It became about those secondary spaces that had that potential, but perhaps hadn’t been realized. Alan Pert framed it as the “ten thousand things” [in reference to the essay “Ten Thousand Things: Notes on a Construct of Largeness, Multiplicity and Moral Statehood” by Jianfei Zhu 1 ]. He drew a wonderful figure-ground map of the wider area and counted up all these leftover parcels. They’re not part of Bridge Road but they contribute to it. Where do they fall, if they don’t sit within a development site? It triggered a discussion with our staff, who said, “If we were asked to do a streetscape masterplan … would we look at all these other contributing factors? How do you map it? How do you understand it and capture it? For us, as a professional practice, it’s incredibly useful to stretch people’s thinking in that regard.

DL: Some of the thoughts were, “Well, okay, the strip will be the strip. Maybe you bolster the side streets first and eventually they will spread, and as you get more activation on the side streets, it will leak its way onto the main street.”

LS: Thinking broadly again, what does the future shopping strip look like? What ideas excite you most?

OH: The idea of a more flexible urban environment. The good ones have got that messiness, that grit. I don’t mean they’re grungy. Quite often you’ll see those shopping strips where people are using the street and you think, “I’m not sure they’re allowed to be doing that, but it’s great that they are.” [In these situations] the councils give them limitations, but also step back. Currently [Bridge Road is] so heavily regulated that the quality of the public realm suffers. Many of our colleagues who live in the area and attended the forum said, “We desperately want to come and use Bridge Road but there’s no driver for us to do it.” It’s about finding those attractors, and they’re not always about a retail shop or a supermarket or a park. They’re those third places that allow you to do things other than just shop or work. There were also interesting discussions around identifying the existing [building] typology and finding ways to adjust it in order to provide access to the upper storey.

LS: You’ve said that “Bridge Road now has the opportunity to find itself, and it needs to do that first.” Who drives that process?

DL: We’ll carry the conversation on. On the last day, [Mayor] Phillip Vlahogiannis, who grew up here, spoke about what the character used to be: local families, living their local lives. They’d go to the cinema on the street, they’d go to the butcher and the greengrocer. Bridge Road then was a high street that had a sense of what it was and whose community it was. He said we should be looking to see who our community is now. Unlike a regional town, the population is not disappearing. There are three applications [with the council] for new twelve-storey developments in this area, for another few hundred people to live literally on the street. So the population will increase and it will drive a desire for something.

LS: But you don’t really know who they are, or–

DL: Does it matter? As designers and solution creators, you can get bogged down with “it has to be this.” You need to step back and say – “You know what? Life is messy.”

1. Jianfei Zhu, “Ten Thousand Things: Notes on a Construct of Largeness, Multiplicity and Moral Statehood” in Christopher C. M. Lee (ed), Common Frameworks: Rethinking the Developmental City in China, Part 1: Xiamen – The Megaplot (Cambridge MA: Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2013), pp 29–43.

Source

Practice

Published online: 2 May 2016

Words:

Lucy Salt

Images:

Melbourne School of Design,

Ricky Ray Ricardo,

Tract Consultants

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2015