The freedom of movement and play

As the German pedagogue Friedrich Froebel said, “Play is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for it alone is the free expression of what is in a child’s soul.” With 75 percent of brain development occurring after birth, play is considered essential to healthy development for children and adolescents. Through play we learn the skills we need to survive and thrive as a species. Play develops skills in problem solving, creativity, social skills, empathy and physical and cognitive development.

But over the past 40 years, we have seen a steady decline in the number of hours that children spend playing outdoors and actively walking or cycling to school. A majority of Australian children do not meet the recommended minimum daily physical activity and the number of children using active transport (walking, cycling) has declined by 42 percent since the 1970s.1 As has been described by VicHealth principal adviser Dr Lyn Roberts, Australian children are some of the most “chauffeured” children in the world. Along with a decline in active play and transport, comes a significant rise in childhood obesity over the past decade, with now one in four Australian children overweight or obese.2

Children in Singapore, walking to school through the neighbourhood community gardens.

Image: courtesy Natalia Krysiak

The increasingly sedentary lives of Australian children has been attributed to a range of factors including parental concerns around safety and an increase of screen-based entertainment. Nonetheless, given that the design and planning of our cities can be fundamental in facilitating healthy lifestyles, design opportunities should be sought which encourage children to partake in active transport, play and incidental physical activity.

So, how can we place the child “user” at the forefront of city design, and ensure that the built environment is one where children can thrive?

A walkable network of play and learning opportunities

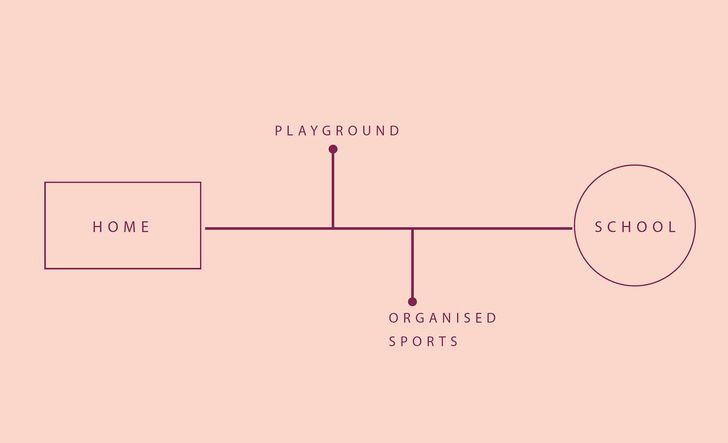

Children’s everyday lives are often limited to three distinct zones: the home, the school and the playground (or facilities for organized after-school activities). Even though these spaces are designed and intended for children, they are often heavily regulated by adults, allowing few opportunities for children to adapt or take ownership. Furthermore, these spaces often become “destinations” which require parents to drive their child and usually remain for the duration of “play to occur” in order to supervise and chauffeur them back (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Car-centric children’s destinations

Image: courtesy Natalia Krysiak

This is very different to how children would play in previous generations, with play often occurring in driveways, on streets and in underutilized pockets of space throughout cities. As our cities continue to densify and open space becomes more valuable, it is critical to consider how we can embed children’s needs for play into the design of our cities, without the reliance on the car and constant parent supervision.

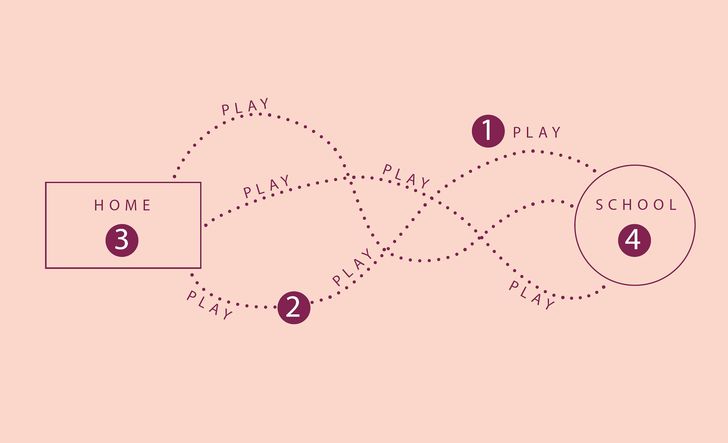

Research undertaken as part of the 2017 David Lindner Prize, proposes a series of walkable child-centric networks to be overlaid onto new and existing neighborhoods. These would create incidental opportunities for exploration, play and social exchange (Figure 2). Four key elements have been considered in order to allow this network to occur:

1. Play opportunities within the public realm;

2. Safe travel routes to enable children’s independence;

3. Play in high-density housing; and

4. School networks which filter into the public realm.

These four elements when combined together, allow a complex network of play and learning opportunities to take place throughout the public realm, with home and school acting as the anchor points for ensuring that interventions are well supported and thriving.

Figure 2: Walkable children’s networks

Image: courtesy Natalia Krysiak

1. Play in the urban realm

One of the principles in creating a more playful city is to dispel the perception of play as something that should only occur in the enclosed “playground” and instead allow it to naturally filter into every corner, cranny and void throughout the city. Opportunities for play should be generously applied throughout neighbourhoods and envisaged as one large networked playscape which becomes a natural part of city life. Neighbourhoods should develop comprehensive play network strategies to be applied to their urban fabric, ensuring that no child has to walk further than 500 metres to a space for play. Providing “incidental play” opportunities through road closures for “street play”, underutilized spaces, bus stops and wild nature pockets will encourage an active community where children’s play is prioritized throughout, rather than segregated to designated zones.

2. Safe travel routes to enable children’s independence

Alongside a comprehensive network of play opportunities, it is vital for designers and planners to consider the ways in which children can access these spaces independently. This has paramount importance in enabling children to take control of their lives and play behaviours and take an active part in neighbourhood life. Evidence suggests that the two key aspects of enabling children to independently access destinations is firstly ensuring proximity and secondly, safety (particularly from traffic). To make active independent travel a viable option, councils, designers and planners must ensure proximity of schools and other destinations to children within the local neighbourhood, understand children’s common travel routes and invest in traffic control and supportive infrastructure within these routes. Children’s designated travel routes should be mapped and child-friendly initiatives such as community signage, playful games and safe pedestrian crossings applied to these routes.

Children splashing in water, Zhangjiagang Town River Reconstruction by Botao Landscape.

Image: courtesy Natalia Krysiak

3. Play in high density housing

The reality of families with children living in high density dwellings is becoming an increasingly common occurrence, particularly in Sydney where 25 percent of apartment residents are already families with children.3 To ensure that children growing up in apartments have access to safe play space both indoors and outdoors, it is paramount that guidelines and policies be developed to facilitate this. Shared common areas such as lobbies, corridors and courtyards have a vital role in providing additional space for play and recreation. It is important to note that even when these spaces are provided for shared use, strata rules can inflict certain regulations on residents such as “no ball playing” which invalidates the benefits of these spaces particularly for children. Parents also report that other residents will often complain about the sound of children playing, creating a perception that it is socially unacceptable for children to impede on the peaceful lives of other residents. Unless we can actively encourage play in high-density dwellings, through good design and policies, children living in apartments will be at loss with negative consequences to their health and wellbeing.

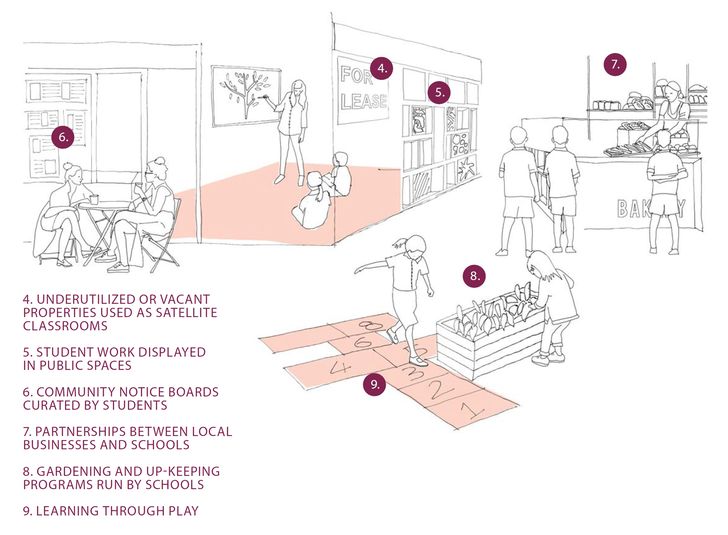

4. Schools as networks

Schools can play an important role as spaces for collaboration and exchange of knowledge between the community and the local children. Synergies between local businesses and schools should be sought, with the purpose of fostering deep and meaningful relationships between children and their neighbourhood. Simple interventions such as public display of children’s art work, gardening and upkeep programs and playful games, will provide children with a sense of belonging and ownership within their community. By considering schools as networks which extend beyond their physical boundary, the school becomes more than just a building but an important social anchor for facilitating a child-friendly city.

Schools as networks which filter into the public realm. Image from ‘Where do the Children Play’ report.

Image: courtesy Natalia Krysiak

neighbourhood?

How different would a child-friendly city be?

When all of these four elements come together, they begin to form a meaningful network of children’s play and learning opportunities which are embedded within the community. By bringing children’s needs to the forefront of neighbourhood design, a series of important questions will start to emerge such as: how will children living in this community walk independently to school? Have play opportunities been considered along designated safe travel routes? Where are the opportunities for children to gather and take ownership of their neighbourhood?

Imagine if every developer, architect and planner were asked these simple questions when submitting a development proposal – how different would our cities be?

The full report “Where do the Children Play? Designing child-friendly compact cities” can be found here.

1. Active Healthy Kids Australia. (2015). ‘The Road Less Travelled: The 2015 Active Healthy Kids Australia Progress Report Card on Active Transport for Children and Young People’, Adelaide, South Australia: Active Healthy Kids Australia.

2. Childhood overweight and obesity. (2014). Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

3. Census of Population and Housing (2016)