Today’s environmental challenges – such as climate change and biodiversity loss – are highly complex and unpredictable. Learning how to design with uncertainty1 is one of the most important tasks we face in the twenty- first century. But while chaos theory and complexity studies are hot topics in modern sciences, the word “complexity” in the design discourse rarely expands beyond its colloquial meaning. In ecological design the oversimplified, naturalistic notion of “returning an ecosystem to its pristine pre-settlement conditions” is still widely perceived as an acceptable description of what ecological design is about. Our design language is increasingly disconnected from modern sciences and as a result, it is poorly equipped to engage with the complexity and uncertainty of today’s challenges.

The language of complexity in modern sciences

Since the time of René Descartes and Isaac Newton, scientists believed that the world could be understood in perfection by breaking complex ideas down to their simplest components. This influential concept, called reductionism, suggested that if we understand the smallest components in isolation, we can then understand the whole. It was an immensely powerful concept and has been the basis of many scientific studies ever since. However, some scientists have started to see the limits of this assumption. They have observed phenomena that suggest that the whole is simply not the sum of all parts. For example, the ability of simple-minded ants to carry out highly coordinated adaptive tasks without any central control defies reductionist theories to understand it. Similar phenomena also occur in bird flocking, fish schooling, slime mould colonies and the biology of our very own brain.2 These previously unexplained properties, namely emergent behaviour, nonlinear interaction and self-organization, are now trademarks for complex systems. In his seminal writing, physicist Jochen Fromm3 described the essence of complex systems simply:

One water molecule is not fluid,

one gold atom is not metallic,

one neuron is not conscious,

one amino acid is not alive,

one sound is not eloquent.

Likewise in ecology, many old paradigms have roots in reductionism. Pioneered by Henry Cowles and Frederic Clements in 1899 and 1916 respectively, the old paradigm of ecological succession was sequential, with each ecosystem eventually reaching an optimal state of equilibrium. This philosophy is what the naturalistic notion of “pristine pre-settlement condition” is loosely based on. Since then, ecologists have shifted away from the idea of a singular climax state to consider more factors across multiple scales and have moved toward concepts that are much more dynamic. Processes and interactions at multiple scales are now key drivers of succession – ecological science has become a large body of work with a rich vocabulary. The naturalistic interpretation of ecological design simply fails to engage with the complexity of our ecosystems.

While low-intensity ecological burn is an effective tool for biodiversity restoration, severe bushfire can push an ecosystem over a threshold where recovery becomes impossible.

Image: Wai Kin Tsui

Nevertheless, understanding a complicated body of scientific work is not an easy task for many. To tackle this, Brian Walker and David Salt have written two books4 on the concept of “resilience thinking,” with a specific emphasis on reaching a wider audience, explaining the complexity in social-ecological systems in simpler terms. In Resilience Thinking they introduce a framework that focuses on changes and coping with disturbance, as opposed to striving for consistency. This framework encourages landowners to focus on thresholds and regime shifts. They also repeatedly warn the reader against models that are based on average conditions and the tendency to consider components in isolation from others.

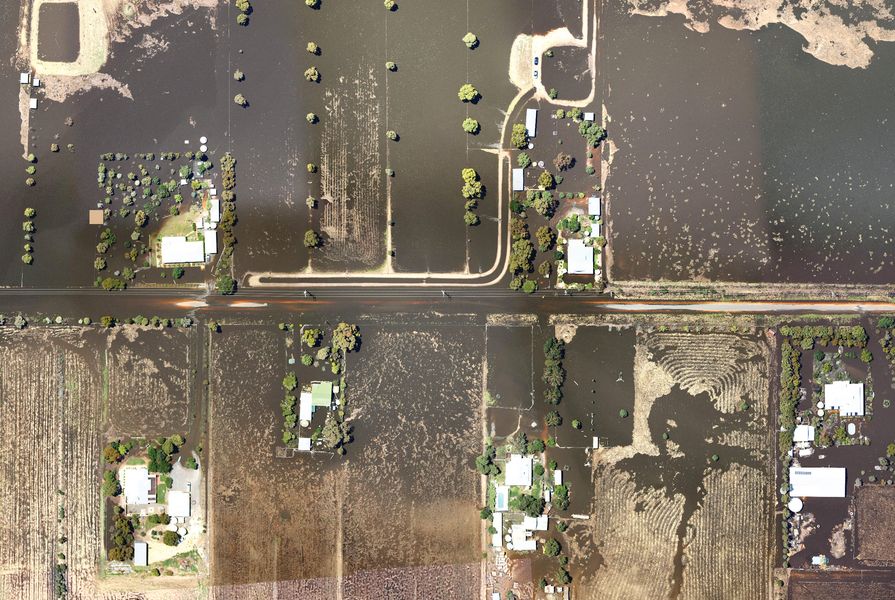

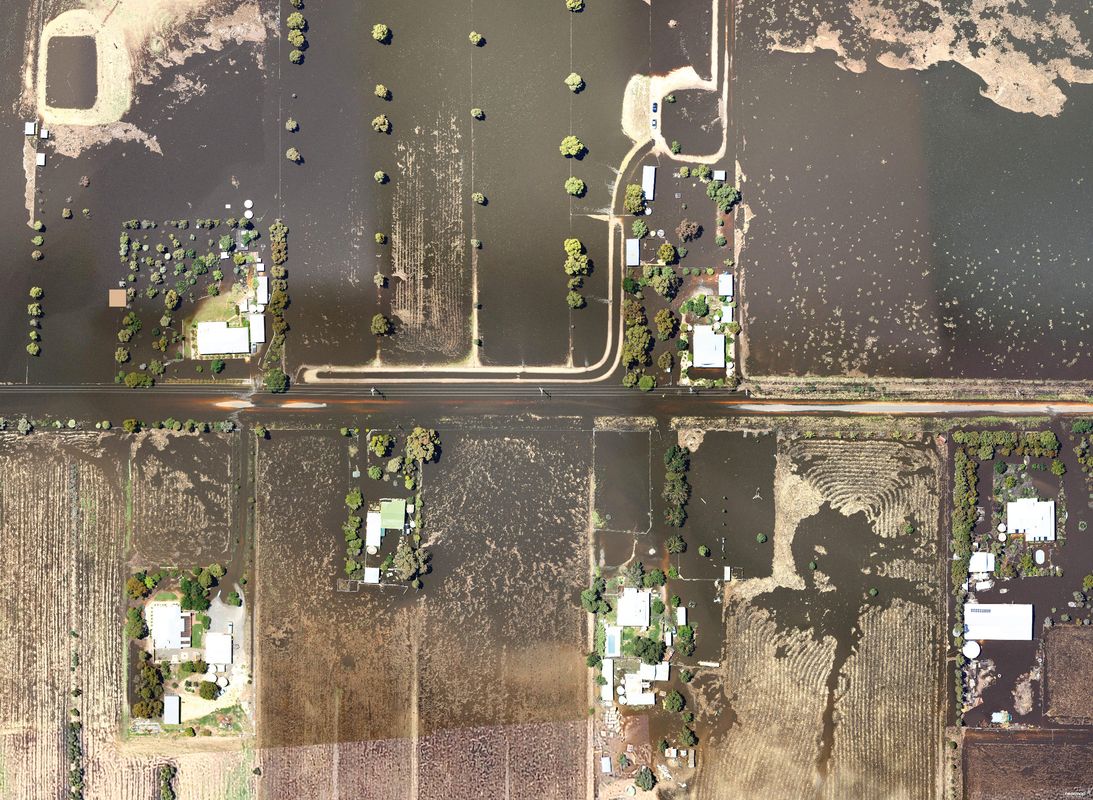

In Walker and Salt’s analysis of the Goulburn Broken Catchment in Australia, they critique the clearing of deep-rooted native forests in order to farm shallow- rooted pastures or crops. Without addressing the system-wide impact of rising groundwater levels and salinity, many farmers are now dangerously close to a threshold of collapse, relying heavily on irrigation and pumping to maintain their profits. They have lost their resilience to any more shocks, such as droughts and floods, which will become more frequent as a result of climate change.

From Ian McHarg’s book Design with Nature to Bruce Mackenzie’s pioneering of the Sydney Bush School movement, designers have done tremendous work in conservation. But it’s now time to renew their borrowed language of ecological design and prepare for a future of complexity. This doesn’t mean that all the old ideas are obsolete. Instead, the language of complexity enriches the existing body of knowledge, and this new discourse is going to bring new perspectives to some age-old controversies.

Benefits of designing with complexity

Ecological design is often criticized for being nostalgic and passive. Indeed, the old naturalistic paradigm of conservation is deterministic, with a primary focus on eliminating change and replicating the past. In contrast, designers of complexity engage with uncertainty. Emergent behaviours, nonlinear interactions and self-organizing phenomena are all part of our ecosystems. These uncertainties now become inherent frameworks for design generation, rather than anomalies to be swept under the rug. Similar to the idea of parametric design, complexity designers design the process and control the outcome – only this time, designers of complexity design with real social-ecological processes and take advantage of the inherent dynamics within. Examples of this design approach can be found in two entries in the Downsview Park Toronto urban park design competition: Emergent Ecologies by James Corner Field Operations and Stan Allen, and Emergent Landscapes by Brown and Storey Architects.5 Both concepts use self-organization as the basis of their design theories. In practice, designers could always collaborate with ecologists for their professional opinion. But if designers want to expand their role in confronting the challenges of this century, a renewed creative agency in ecological design might be the most compelling argument for designers to develop a deeper scientific literacy.

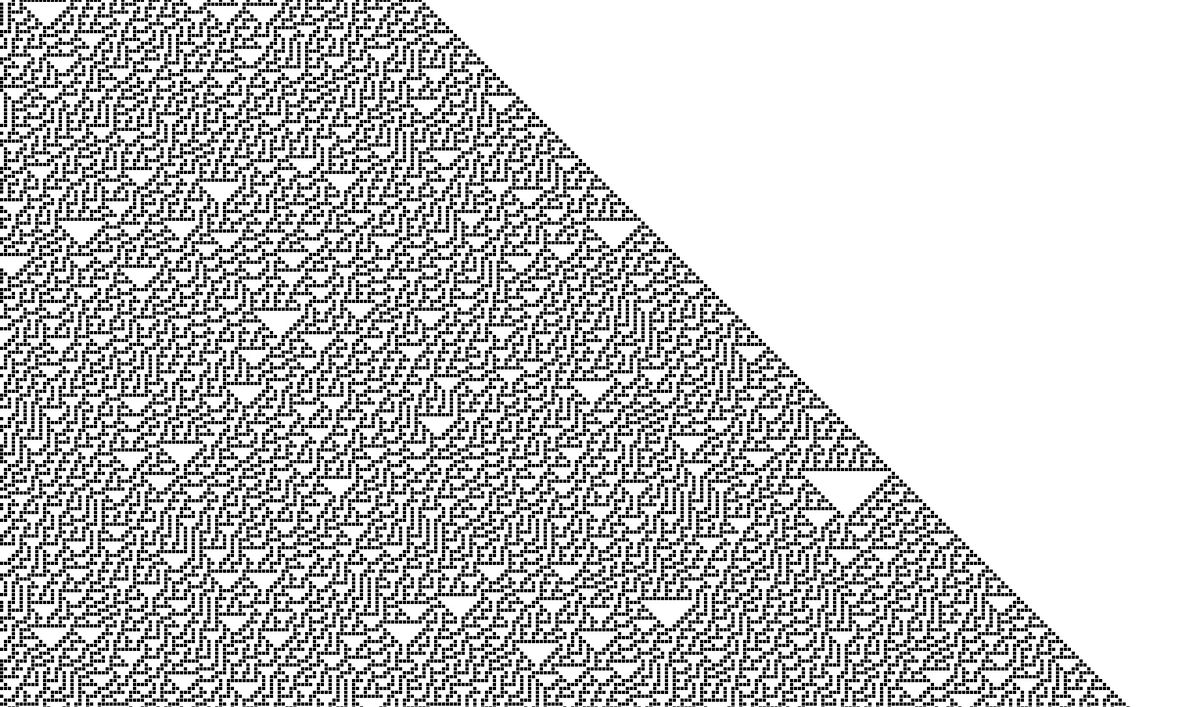

The pattern on a Textile Cone shell is remarkably similar to Stephen Wolfram’s Rule 30 (next image).

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Ecological design has also been criticized for a more practical reason. Some argue that ecological conservation is an unrealistically utopian notion that will never work in areas that are highly disturbed – places where landscape architects often find themselves working. If we consider the naturalistic notion of ecological design, then this is a convincing argument. However, when conservationists apply the resilience thinking theory and consider ecology and human settlement as one complex social-ecological network, the reverse is also valid.

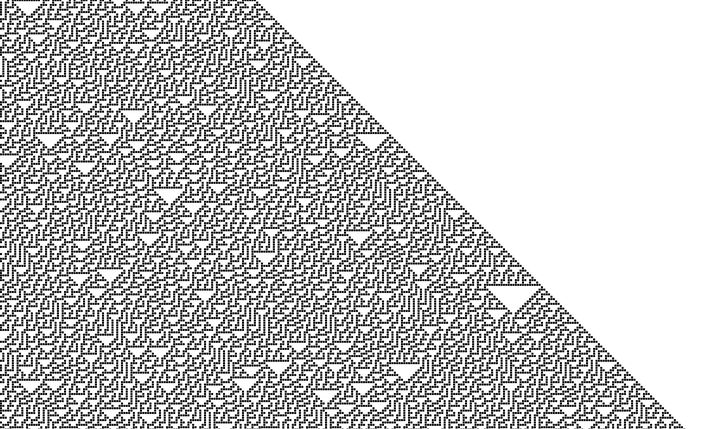

Stephen Wolfram’s Rule 30, an iconic pattern that demonstrates how simple rules can produce complex systems.

Image: Cellular Automata Generator

A number of scientists have concluded that the success of conservation will be increasingly dependent on the ability of urbanites to maintain a connection with nature in places where they work and live. Many geographers and scientists believe that direct experience with nature is one of the most influential factors for public support, and ultimately global conservation efforts require funding, votes and leadership to become successful. While people’s experience with the wilderness is reducing, direct experience with urban nature has now become the main source of reference for many people across the world. Some ecologists believe that personal experience of nature is so important that they have to accept modified or novel ecosystems in urban environments. Under this framework of thinking, conservation projects are both conservators of experience and catalysts for positive change.

From designing with the dynamic properties of complex systems to understanding our social and ecological realms as one connected entity, the case for engaging with complexity in ecological design is compelling. The benefits extend well beyond the necessity of scientific accuracy, and there is a growing body of work under the umbrella term “emergence” in both landscape architecture and architecture. As today’s environmental challenges grow to become more complex and dynamic, it is time to respond in a similar vein.

1. Matthew Hamilton and Niki Schwabe, “Designing with uncertainty,” Landscape Architecture Australia, issue 151, August 2016.

2. An authoritative introduction to complexity from the physicist’s point of view is Melanie Mitchell’s online course Introduction to Complexity by the Santa Fe Institute. Periodically available at complexityexplorer.org. Nowadays, physicists use the term “chaos theory” or “complex system sciences” to describe this field of study.

3. Jochen Fromm, The Emergence of Complexity (Kassel: Kassel University Press GmbH, 2004).

4. Brian Walker and David Salt, Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2006) and Resilience Practice: Building Capacity to Absorb Disturbance and Maintain Function (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2012).

5. Both entries were used as examples in Blake Belanger’s thesis, Landscape Emergence (the University of Colorado Denver, 2006).

Source

Practice

Published online: 5 Dec 2017

Words:

Wai Kin Tsui

Images:

Cellular Automata Generator,

Nearmap,

Wai Kin Tsui,

Wikimedia Commons

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2017