Kjetil Trædal Thorsen is co-founder of Snøhetta, a transdisciplinary design practice with offices in Oslo, New York, San Francisco, Innsbruck and Singapore.

Claire Martin: Snøhetta’s practice combines architecture, interior, landscape and brand design. What is the value of transdisciplinary design?

Kjetil Trædal Thorsen: When Snøhetta was established, there wasn’t really a definition of transdisciplinary practice, but the concept of multidisciplinary practice was starting to emerge, which obviously means putting different professions around the same table and trying to solve similar problems at the same time. This was in around 1987. The time seemed ripe for letting [different] specialists into the same room and having them work together on similar issues. There wasn’t any cross-referencing back then, either, in terms of how certain types of common problems should be solved in a horizontal flow between professions. That [technique] has slowly developed into what we call “ transpositional working relationships,” where we go beyond placing various professions around the same table, to actually switching between professions – so the architect becomes the artist, the artist becomes the sociologist and so forth. We do this because we believe everyone carries specialist knowledge, and in this type of work we’re more interested in the profession plus the person. It means you’re getting more back than just a knowledge base that is conceived within every profession. I think what we’ve seen with this transpositional method, in creative work especially, is that people leave their basic responsibilities behind and they’re not blocked by what might catch up with them later.

CM: You describe this method as getting outside your comfort zone.

KTT: Yes, I think that’s it … definitely outside the comfort zone, but at the same time, with no real consequence should you make a mistake. The effect is that you’re getting the full person and there is no real consequence, you can speak freely and you could [for example] get the musician in the engineer to come out. That’s what we’re looking at with this transpositional meth od … but that said, its nearly thirty years since we started with “multidisciplinary,” the term at the time, and things haven’t really changed that much. In many professions people still sit within their small rooms and think only of themselves and there is little horizontal sharing on the issues that are being studied. We see that in all the work being done on the carbon crisis and CO2-negative buildings – so many parallel activities happening and very little horizontal communication. It’s taken a long time to put [the concept of transdisciplinary practice] into our own words – you start off by doing something intuitively and it’s only later that you understand what you’ve done. By understanding why you are doing what you are doing, you can then start to organize it and systemize it a little bit more, and all of a sudden you see the effects.

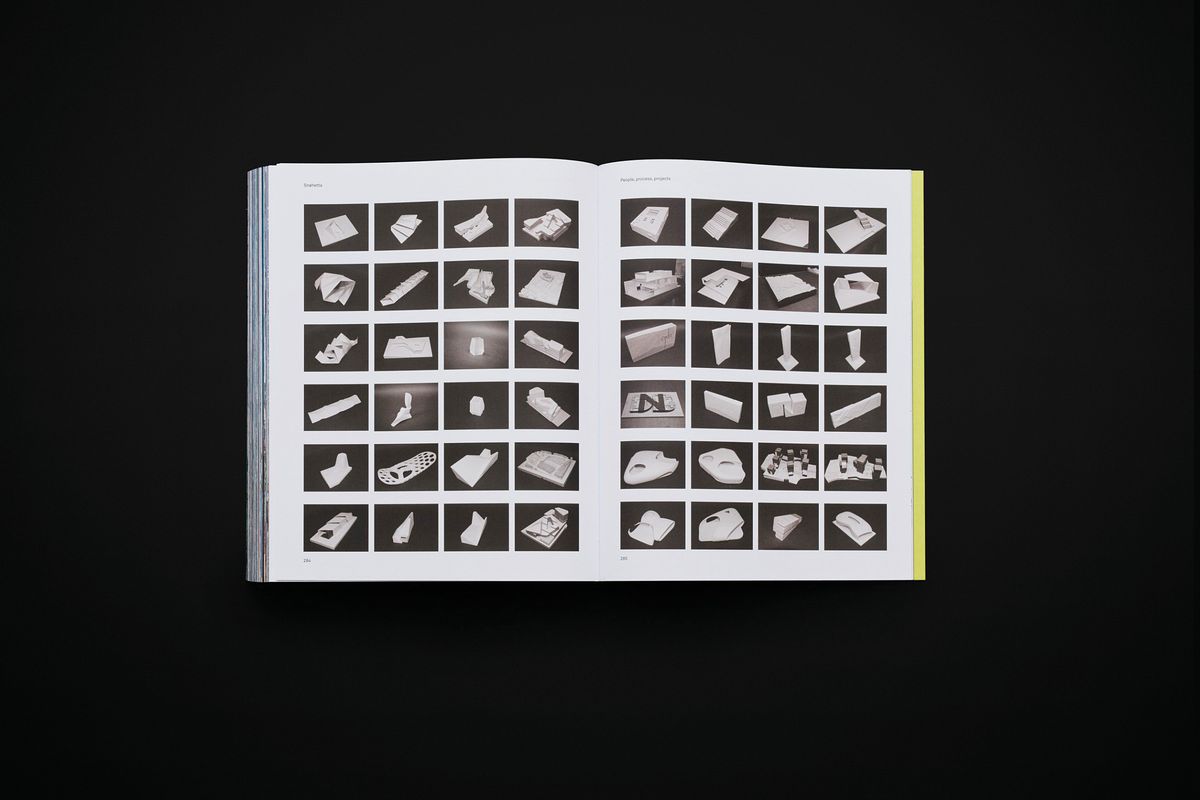

Rapid prototyping allows the “testing of abstract ideas [and] putting things together that haven’t been put together before,” often leading to unexpected outcomes.

Image: Jeff Goldberg/Esto

CM: We are interested in what you think the advantages of rapid prototyping are.

KTT: Again, that’s become part of how to communicate. The things Snøhetta is focused on now are the people–process relationships, not so much the end result. The result is the result of the people–process relationship. You can assume that there isn’t only one solution to a problem, and the project you end up with depends on how you set up the relationship. The process and how the team works is really very important for the result; in order to be able to communicate that and test things out during the process period, you need to be able to develop both large-scale and small-scale prototypes of what you are thinking. It’s more than just making models of whatever you’re designing, it’s everything from testing abstract ideas to putting things together that haven’t been put together before, to testing out the physicality of the element, the weight, the smell, everything that a material might contain, and putting that into the context of the process. By doing that, you might end up somewhere else again, so the tools you’re using, how you put people together and how you design the process all determine the result of those projects.

Ricky Ricardo: Your practice is large by many standards and you work on projects around the globe. What are the risks associated with the internationalization of architecture?

KTT: There is huge risk when it comes to the international aspects of architecture, especially if you are swapping styles, let’s say. Think of certain [international] brand names with specific attitudes toward their projects – the context can be forgotten in the project and it becomes like collecting art. I think there are different aspects to how one could assume the involvement of foreign practices in a local situation might be. Our approach is that we’re always coming in as a partner and not taking over. We also know from experience that it’s sometimes good to invite someone from the outside [to look in]. It actually triggers things that either you’ve forgotten about or that are too obvious for you to see. It’s something we call local blindness. It’s more about people-to-people relationships than being about buying a piece of architecture. If the internationalization of architecture is a business model, then it doesn’t make much sense. But if it’s a real exchange of cultures and people, in order for us to understand more in both directions, then I would welcome it in Norway. Maybe it is a way of breaking down some of the natural barriers we’ve been carrying with us for so long.

CM: I think the partnership approach is a good one. There are a lot of international architects doing work in Australian cities at the moment and the success of that work will be through those partnerships.

KTT: I’m absolutely certain [it’s a good approach], because in the end it’s not about you or me, in the end it’s about what you get and how you get there. You want these outcomes, whatever they are in the end, to really enhance the environment you’re working in, you want it to be an instrument for developing society, you want it to be an instrument for developing whatever the content might be. You want it to be an instrument to enhance people’s perception of that and what it contains.

Snøhetta and Goksøyr & Martens’ competition entry for the 22 July massacre memorials, which consist of three unique yet coherent memorial places permanently placed at Utøya, Regjeringskvartalet and Sørbråten, Norway.

Image: Snøhetta and Goksøyr & Martens

RR: We are interested in Snøhetta’s competition entry for the 22 July massacre memorials in Norway, and the interpretation of what were two very tragic events [which occurred in 2011]. How did your approach seek to move visitors in terms of their emotional connection to the events, and also figuratively and literally in terms of the site?

KTT: Our approach was that no place is really unique when it comes to a terrorist attack. It might be in the government quarter in Oslo, or on the island of Utøya in Tyrifjorde lake, Buskerud, and you can show that by moving a piece of that place into Oslo, or maybe the other way around. Every place in the mind of a terrorist is the same.

CM: That’s interesting, so you could say it’s a kind of de-territorialization?

KTT: Exactly. Our approach was about trying to show this through the design [developed in cooperation with Goksøyr & Martens]. There were obviously a lot of design details related to that idea as well. But that, to me, was the main setting for what we wanted to say. The winning proposal [by Swedish artist Jonas Dahlberg] with the big cut, or wound, is a very interesting one and I like it. We [Snøhetta] were in fact discussing a similar concept – it was like a slope into the middle of the peninsular – but we left it because it was a wound that would never heal and never grow, so we decided to move away from this particular everlasting cut, an eternal cut. We felt there was too little development in how that particular monument would change over time.

Source

Practice

Published online: 14 Dec 2016

Words:

Claire Martin,

Ricky Ray Ricardo

Images:

Calle Huth,

Jeff Goldberg/Esto,

Snøhetta and Goksøyr & Martens

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2016

![Rapid prototyping allows the “testing of abstract ideas [and] putting things together that haven’t been put together before,” often leading to unexpected outcomes.](https://media5.architecturemedia.net/site_media/media/cache/e3/09/e309ce9d62f19fc419204c065f201736.jpg)

![Rapid prototyping allows the “testing of abstract ideas [and] putting things together that haven’t been put together before,” often leading to unexpected outcomes.](https://media3.architecturemedia.net/site_media/media/cache/6e/62/6e627f1063decef635ad2fa48357a41c.jpg)