University campuses are inevitably a product of the accretions and deletions that result from ongoing expansion and change over time. Throughout its history the North Terrace campus of the University of Adelaide has grown, and it is now constrained by North Terrace, the River Torrens, Frome Road and Kintore Avenue. Unsurprisingly, with each stage of expansion, the design style and thinking of the time has been embraced; the campus can be read as a series of historical markers.

These markers extend from the influence of Elsie Cornish during the Walter Bagot era, to the developments of the 1960s and 1970s during the enormous national growth of universities, to the more recent additions including the Taylor Cullity Lethlean-designed North Terrace, which is integrated into the forecourts of the adjacent university buildings, including the redeveloped Goodman Crescent.

Major changes in the late 1960s and early 1970s resulted in several new buildings. Landscapes associated with these buildings include a now-degraded courtyard by John Stevens in the Bates Smart and McCutcheon-designed Napier Building. In better condition is the Wills Courtyard, which was built in 1973 as part of a three-stage development designed by Hassell.

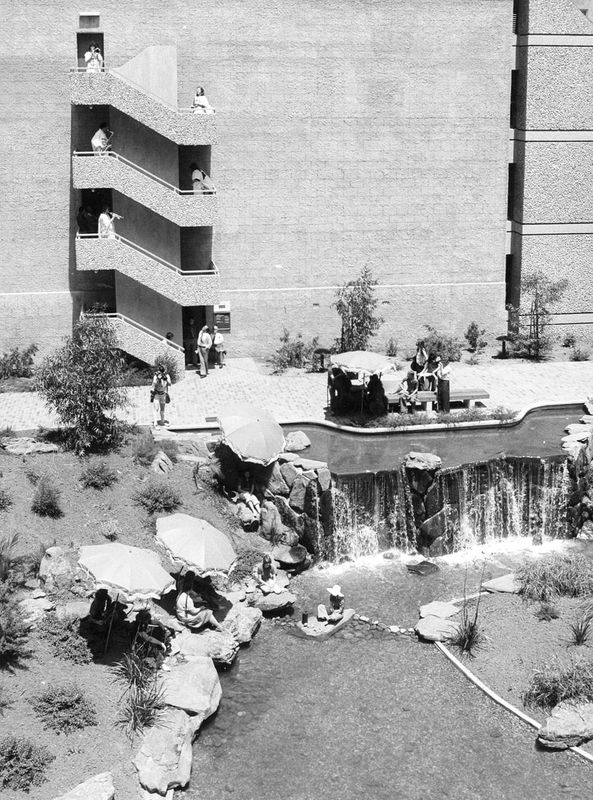

The Wills Courtyard project was a collaboration between architect David Cant, landscape architect Ian Barwick and the then head of the University of Adelaide’s botany department, Dr Brian Walmsley. The team was under instruction from university administration to “fill up the courtyard” to reduce the risk of students using the space for demonstrations, particularly given the space’s close proximity to the vice-chancellor’s office.

The curves of the pond and retaining walls dictate the path through the site.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The design deals with the dramatic grade change, a feature of the whole campus as it tumbles from the edge of North Terrace to the banks of the Torrens River. The central feature of the design is the two-metre high waterfall set against a “natural” stone cliff. The waterfall joins the two organically shaped ponds and allows the design to achieve the goal of filling up the courtyard. The sloping beds, natural stone, plant textures and the layering of plant materials create a calm, green haven enclosed by Gothic-style sandstone buildings and the later additions of the 1960s and 1970s.

The courtyard is heavy on red brick, which is cleverly used to create organic directional geometry; the flowing, brick paving forms a “beach” at the water’s edge. Unfortunately, this intriguing element has recently been compromised as new waterproofing is now visible.

Returning in 1972 from landscape architecture studies in Syracuse, New York, Barwick worked for Hassell and Partners, where he established their landscape department. Barwick’s contribution to the project included the design’s sensitive, modernist features, although he left Hassell to set up his own practice before it was completed. The designers’ awareness and appreciation for the greater campus is recognizable in the use of brick-on-edge steps and the recycled stone of the seating wall, which references the existing stonework of the adjacent and historic Elder Hall.

This modern yet contextual approach to the design provides an insight into the sensibilities of the design thinking of the team. The eastern side of the courtyard allows direct pedestrian access through the site, with stairs from Goodman Crescent into what was Hughes Plaza. These shallow steps form one of the main entrances to the recent Hassell-designed Hub Central. Although the articulation from old to new is not as considered as it might be, access through the site from east to west is dictated by the organic curves of the ponds and retaining walls and cleverly connects the once new to the existing entries at different levels.

Dr Walmsley was influential in the decision to plant named Australian natives. The intention was that the courtyard would double as a student learning environment, creating a didactic garden within a small civic space on the campus. This is perhaps the first example of Australian natives being used so deliberately on the campus, although the aim was not to create a stylized Australian landscape. Rather, a combination of Australian natives, including correas, melaleucas, corymbias, banksias and cycads, and non-natives such as bamboos, pandanas and ferns were selected to provide textural variation and to create an atmosphere of calm, more in line with Japanese garden traditions.

The site is a “peaceful haven within the busy university campus.”

Image: Peter Bennetts

There have been some damaging changes to the courtyard’s design, including replacing the elegant, dark modernist balustrade with larger-dimensioned standardized stainless steel, and the unfortunate addition of a Confucius statue. While the now-mature lemon-scented gums are a real asset to the courtyard, much of the original planting needs restoration; over time, gaps in the understorey have become evident. Despite this, and perhaps surprisingly, the courtyard is in good condition.

The space still retains its sense of calm and works as a delightful experience, possibly due to the lack of a unifying masterplan for the campus. Campus masterplans can have a homogenizing effect where furniture, lighting and paving materials would be standardized at the expense of individual spaces and architectural conglomerates.

Campuses are built timelines and physical expressions of history; they track global styles and economic trends. Most notable on Adelaide’s campus are the original sandstone buildings, the later Woods Bagot buildings, the Napier and Schultz towers of the 1960s and the extension to the Mitchell in the 1970s. It is unfortunate that the landscapes associated with these buildings have often been neglected and forgotten, such as the once-wonderful Napier Plaza by Stevens, which is in dire need of restoration. Importantly, Wills Courtyard is in good structural condition and is highly suitable for restoration, which will enhance its status as “a peaceful haven within the busy university campus.”

Credits

- Project

- Willis Courtyard

- Architect

-

David Cant

- Landscape architect

-

Ian Barwick

- None

-

Brian Walmsley

- Site Details

-

Location

Adelaide,

SA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Review

Published online: 3 May 2016

Words:

Tanya Court,

Jessica Miley

Images:

Courtesy of the University of Adelaide,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2012