Around Woolloomooloo Bay tanned bodies and coffee-sipping cafe-goers bask in the sun as if life is one big luxury good. An advertisement declares that a $1.25-million, two-bedroom apartment is “surrounded by iconic Sydney landmarks and a host of fine dining options, [offering] an envious waterfront lifestyle.” This is global Sydney. It is the kind of image you can put on brochures and sell in package deals to tourists. In stark contrast, less than a minute away, there is deprivation and vulnerability. Sydney’s highest concentration of homeless people sleep rough in the public spaces of Woolloomooloo.

In the 1970s green bans saved Woolloomooloo from high-rise commercial development. Built instead, in 1974, was a redevelopment project involving a significant amount of public housing and heritage building stock. One of the most creative urban projects in Australia’s history, it came into being due to the cooperation of all levels of government. Despite these promising beginnings the area is in need of renewal and better management. Even though the state government is responsible for much of the land here, the City of Sydney is trying to revitalize the areas it has jurisdiction over with an inclusive and practical strategy to encourage middle-class locals to use the public space alongside more disadvantaged locals and the homeless population. The recent redesign of Walla Mulla and Bourke Street Parks, by the landscape architecture firm Terragram, is emblematic of this ambition.

When I arrive at Walla Mulla Park there are groups of homeless people scattered throughout the park. The main group occupies around four square metres of space defined by scattered sleeping bags, pillows, and “survival” swags. A man with greying hair, dressed in jeans and thongs, walks into the park with a duffle bag, a suitcase with wheels and a sports backpack resting on top of the suitcase. He wheels them through the park and puts them down next to another man sleeping in paint-splattered shorts and work boots. He sets up his sleeping berth for the night, disappears for a moment to buy a bottle of beer, returns, and reclines on his blanket before taking out some spectacles and a paperback. A variety of different routines unfold before my eyes as I sit and take notes.

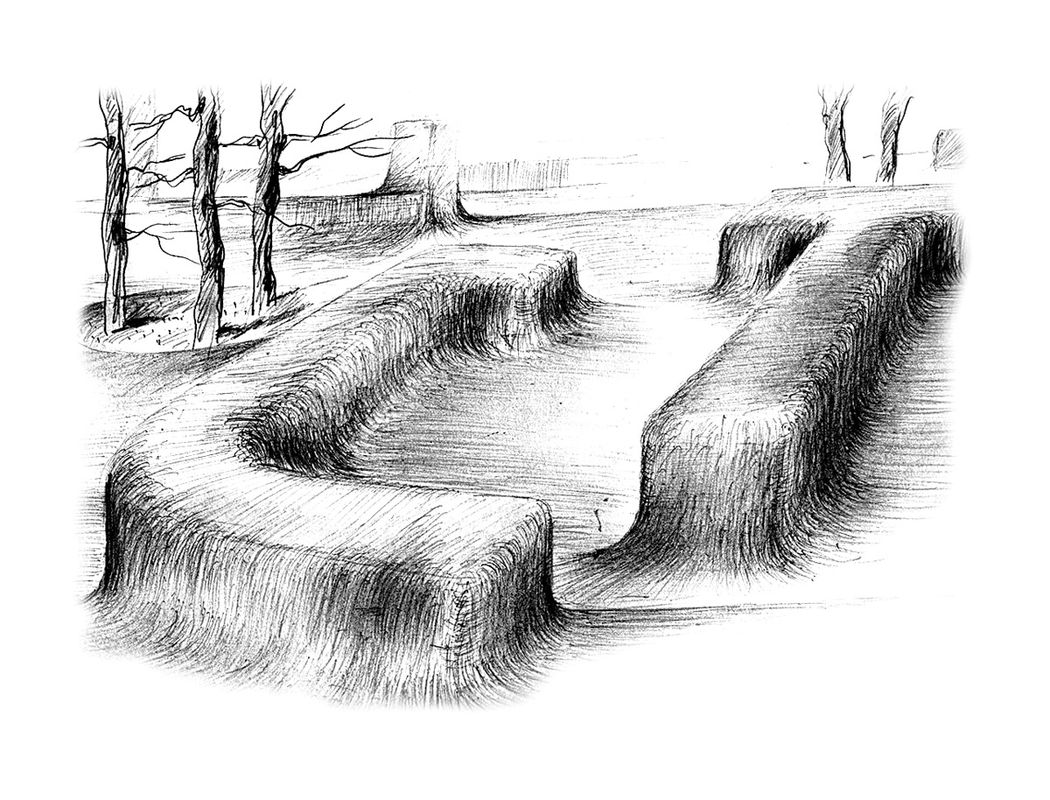

New and recycled concrete pavers and dividing concrete strips are used for the park’s ground surface.

Image: Vladimir Sitta

Walla Mulla and Bourke Street Parks are two of a series of public spaces underneath a rail viaduct in Woolloomooloo. The viaduct might be a 1970s engineering innovation but the novelist Ruth Park suggested that even “in poor decrepit Woolloomooloo the thing is a blasphemy.” The public spaces beneath the viaduct are left over from metropolitan-scale transport planning rather than being spaces created expressly for the local community. Around seventy homeless people sleep rough in the rain shadow beneath the six-hundred-metre-long viaduct. There were previously around ninety rough sleepers but the City of Sydney Homelessness Unit has managed to find accommodation for twenty of them over the last year.

The brief for the redesign of the parks realistically acknowledged that they would continue to attract the homeless. Terragram suggests that it was a delicate situation for the City of Sydney, as they did not want to appear to legitimize chronic homelessness through the provision of amenities. The resulting strategy involved encouraging a shared ownership of the site through generous sight lines, and programs such as community gardens that encourage locals to actively and regularly use the space.

Terragram has keenly observed the patterns of use in the parks. In Walla Mulla Park, the design of seating supports the existing patterns of behaviour, as the homeless gather in small groups in different parts of the site. The boomerang-like forms of the seating can accommodate gatherings of people and also allow individuals to maintain their personal space. The spacing of the seating allows daily cleaning to take place as there are wide enough corridors for council cleaning machines to pass by. The ground surface of Walla Mulla Park is mostly paved and integrates a range of recycled and new masonry as well as concrete dividing strips. Paving patterns exhibit dynamic changes of direction that direct run-off from rainwater and pressure cleaning. There are no stormwater pits in the parks; this decision was made to reduce the possibility of concealing illicit drugs and equipment.

At night, intense lighting makes the toilet a lantern in the park, and facilitates surveillance.

Image: Vladimir Sitta

The eclectic geometries and material create a vibrant and expressive spaces that seems more Latin than Anglo-Saxon in design inspiration. Lush, subtropical species such as mature kentia palms (Howea forsteriana) and flowering climbers support the vibrant aesthetic of Walla Mulla Park. The trellis against the wall of the neighbouring hostel will gradually be transformed into a green wall and cascading green roof to a new toilet block. Likewise, a stainless steel climbing structure is already luxuriant with a grapevine spilling over from a neighbouring property. One of two lozenge-shaped lawns invites lounging in the centre of Walla Mulla Park. It is here that I observe the locals and write my notes. Elegant-yet-tough, graffiti-resistant toilet blocks designed for the two parks are by Chris Elliott Architects and are characteristic of this energetic design language. The mix of white eggshell-like mosaic tiles, laser-cut stainless steel and suspended wing-like roofs is a breezy and fresh touch in this tough area. At night, bright lighting reflects off the roofs of the structures so that they glow like lanterns.

Just as important as the work by Terragram is the role that Mike Fish, Sydney City Council’s public space liaison officer, plays in the success of these spaces. On first-name bases with the homeless residents of the area, Fish’s role is to liaise with all users of the park and to manage the hygiene and safety of the public spaces. He arrives at work early and visits the various public spaces to resolve any problems. He makes sure the homeless gather their belongings and store then safely during the daily 9 am cleaning of the park.

The public realm exists as a series of rules and regulations expressing the tension between middle-class desires and the right of all members of the community to spend time in public space. Walla Mulla and Bourke Street Parks are important litmus tests for the future Woolloomooloo. There is more than one way to occupy public space. Terragram explores this political concept in a thoughtful way.

Credits

- Project

- Walla Mulla Park

- Design practice

- Terragram

Surry Hills, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Vladimir Sitta, Robert Faber, Anthony Charlesworth, Anita Madura, Gesine Kippenberg

- Consultants

-

Arborist

Sydney Tree Consultancy

Architect Chris Elliott Architects

BCA consultant Tom Miskovich and Associates

Builder Hansen Yuncken

ESD Cundall Australia

Electrical engineer Webb Australia Group

Heritage consultant Geoffrey Britton

Hydraulic engineer Brendan Dowling

Planner David Crane and Associates

Structural engineer Rooney & Bye

- Site Details

-

Location

Woolloomooloo,

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 21 months

Construction 4 months

Website http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/development/cityimprovements/ParksAndReserves/WallaMullaParkRenewal.asp

Category Landscape / urban

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

City of Sydney

Website cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au

Source

Review

Published online: 28 Apr 2016

Words:

Scott Hawken

Images:

Paul Patterson, City of Sydney,

Terragram,

Vladimir Sitta

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2012