The Goods Line urban renewal project has seen a disused rail corridor reimagined as an elevated park that runs through the heart of Sydney’s most densely populated area. The site began its European history in 1855 as the key access for Australia’s first railway to the port at Darling Harbour. Freight moved through this narrow corridor until 1984, when the last train made its way past the Ultimo Power Station, which was by then vacant (now the Powerhouse Museum). Following decades of disuse, The Goods Line was then reconsidered as the main component of the Ultimo Pedestrian Network. This proposal not only linked Surry Hills with Ultimo and an array of civic institutions but also ensured future access to Darling Harbour and beyond. The first piece of the action was the connection by pedestrian tunnel to Central Station/Railway Square in 1999, arguably Sydney’s busiest public transport hub, while August 2015 saw the first of further major renovations with the opening of The Goods Line North, which runs from Ultimo Road to Macarthur Street. A second stage, The Goods Line South, has been designed but is yet to be constructed.

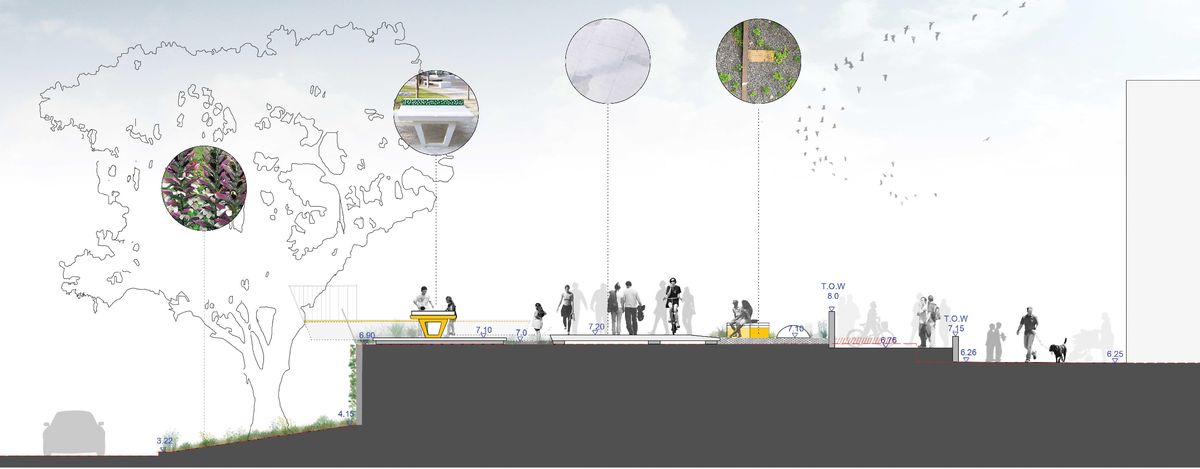

Across increasingly diverse scales and sites, landscape architects creatively consider the urban condition and build upon their potential through coordination with diverse stakeholders and land- holders. For The Goods Line, a New South Wales Government initiative delivered by Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority, these stakeholders included TransGrid, Sydney Trains, the University of Tech- nology, Sydney (UTS), Powerhouse Museum, Sydney TAFE, the ABC and the City of Sydney. From this intriguing site and diverse stakeholder mix, The Goods Line’s designers, Aspect Studios and CHROFI, have created a connected and welcoming green space with a clear narrative and identity. This pedestrian-scale linear park offers respite from the city, bordered to the north-east by a row of existing fig trees and to the south-west by Frank Gehry’s Dr Chau Chak Wing Building at the UTS Business School and the Powerhouse Museum. Here, a serious attempt to accommodate public life encompasses a range of ways to linger in and inhabit a new civic infrastructure through a generous menu of visitor experiences. The selection includes grassed areas, a seating amphitheatre “event platform,” table tennis facilities, a small children’s water playground, a range of furniture including study pods and communal tables, and a collection of interpretative objects and information for the avid history buff. United through a common language of formed concrete, timber, painted steel and exposed rail tracks, the project perches above the original train line and associated infrastructure (including original lever frames), at times visible below footfall and interspersed with a somewhat eclectic but hardy plant mix.

The design offers pedestrians a range of ways to occupy the space with its grass areas, table tennis tables, playground, communal tables and study pods.

Image: Florian Groehn

Critique could be made of the material qualities of the design (there is a lot of concrete) or the planting (it shall grow). But if the metric of a landscape architectural project’s success is occupation of public space (and why not?), then The Goods Line can be deemed a success. After its initial opening, it maintains a constant level of public life, with a steady stream of visitors present by day and by night. Rubbernecked cruise ship tourists take in Gehry’s work and jostle for space with the occupants of this building as well as those from the nearby TAFE and the ABC offices. Business startups hold informal meetings in the public spaces of The Goods Line, and urban hipsters populate the communal tables and study pods, taking advantage of the wi-fi and the coffee available from a seemingly misplaced drive-through-style window. Meanwhile, residents wander in a steady stream through the space, either enticed by its novelty or sense of calm, or for the shortcut it offers to Darling Harbour. This level of occupation is noteworthy, and that this project has been well received by the media is testament to its success, in stark contrast to nearby Barangaroo and its headland park.

The Goods Line is a fine example of a creative response by landscape architects to the myriad yet often overlooked leftover, ill-defined or terrain vague spaces of a city.1 In Landscape Infrastructure , Gerdo Aquino suggests that for cities (such as Sydney) with growing population and competition for space and resources, such contiguous infrastructural networks will be increasingly recognized and valued for their potentially critical, multifunctional, connected, pedestrian-focused and even ecological potential.2 As such, the mandate for landscape architects as critical agents in the creation of similar spaces in the future city is clear.

There is always the danger of being a slave to fashion and this article would not be complete without acknowledging the perhaps inevitable comparison to New York’s globally popular High Line.3 This is, in part, warranted: both projects are indeed pedestrian-oriented and linear and share a narrative of abandoned and reinterpreted railway. Likewise, both attract tourists observing architectural folly and plants are certainly in abundance. However, the resemblance stops there. Unlike the High Line, which is detached from the city fabric, an overlay that pierces built form but little else, Sydney’s The Goods Line offers meaningful, at-grade connections. These connections are/will be to Railway Square and Thomas, Macarthur and Mary Ann Streets, assuring pedestrian access to, from and through the network at a local level and beyond.

Although the project can be compared to New York’s High Line, The Goods Line’s success lies in its engagement with and connections to the city.

Image: Florian Groehn

Perhaps one question regarding this emergent typology would be: Why do elevated linear parks resonate with and capture so well the imagination of citizens, tourists and municipalities alike? Beginning with the Viaduc des Arts et Promenade Plantée in Paris in 1994, it was New York’s High Line that spawned a wave of infrastructure-based re-use projects that continues today, including Mexico City’s Chapultepec elevated park, Rotterdam’s Hofbogen urban park, Philadelphia’s Reading Viaduct open green space and London’s Garden Bridge (although not strictly re-use), as well as New York’s latest offering, The Lowline underground park.

Sydney’s own The Goods Line certainly fits within this remit, but it is perhaps the potential of this successful project to catalyse the rethinking of similar forgotten or overlooked spaces within Australian cities that is of real interest.

1. Ignasi de Sol à -Morales, “Terrain Vague” in Cynthia C. Davidson (ed), Anyplace (New York, NY; Cambridge, Mass.: Anyone Corp; MIT Press, 1995).

2. Ying-Yu Hung and Gerdo Aquino (eds), Landscape Infrastructure: Case Studies by SWA, Second and Revised Edition (Basel: Birkhauser, 2013).

3. James Robertson, “Sydney version of New York High Line to open between Central and Darling Harbour,” The Sydney Morning Herald online, 28 August 2015, smh.com.au/nsw/a-dormant-goods-line-reconnects-sydneys-east-and-west-20150827-gj95kf.html (accessed 24 November 2015).

Credits

- Project

- The Goods Line

- Practice

- ASPECT Studios

Australia

- Practice

- CHROFI

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Consultants

-

Civil and structural engineer

ACOR

Contractor Gartner Rose

Electrical & hydraulic engineer ACOR

Heritage consultant GML Heritage

Interpretive designer Deuce Design

Lighting design Lighting Art and Science

Planning consultant JBA Urban Planning

Precast concrete AR-MA

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens

- Client

-

Client name

Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority

Source

Review

Published online: 12 Sep 2016

Words:

Simon Kilbane

Images:

Aspect Studios,

Florian Groehn

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2016