The Royal Botanic Gardens’ Australian Garden, at Cranbourne in Victoria, is a perplexing design, alternately eliciting delight, ambivalence and even confusion. At the least, it is provocative. My response to it has softened over time, with the maturing of stage 1, but a hint of ambivalence remains. Perhaps not surprisingly, the conduit for this ambivalence is the red sand garden – and the confluence of art and landscape architecture as they meet in this project.

That sand garden. That ubiquitous red sand – are we destined to endlessly replicate the colours of the arid centre, or the distant north, whether in outer-suburban Cranbourne or with the Kimberley stone of Federation Square? And is it appropriate or even desirable to represent – not just to reference, but to represent – the red desert in Melbourne? Admit it, you’ve all thought it, or something like it. I did. Certainly, this was a recurrent thread of conversation among landscape architecture students after the completion of stage 1. The fact that the sand was sourced locally mediated concerns over the provenance of materials that emerged with Federation Square, where the stone is someone else’s country, a long way from Melbourne. Still, it is questionable to produce such a representation in urban Melbourne where this landscape more often exists in the imagination or in advertising.

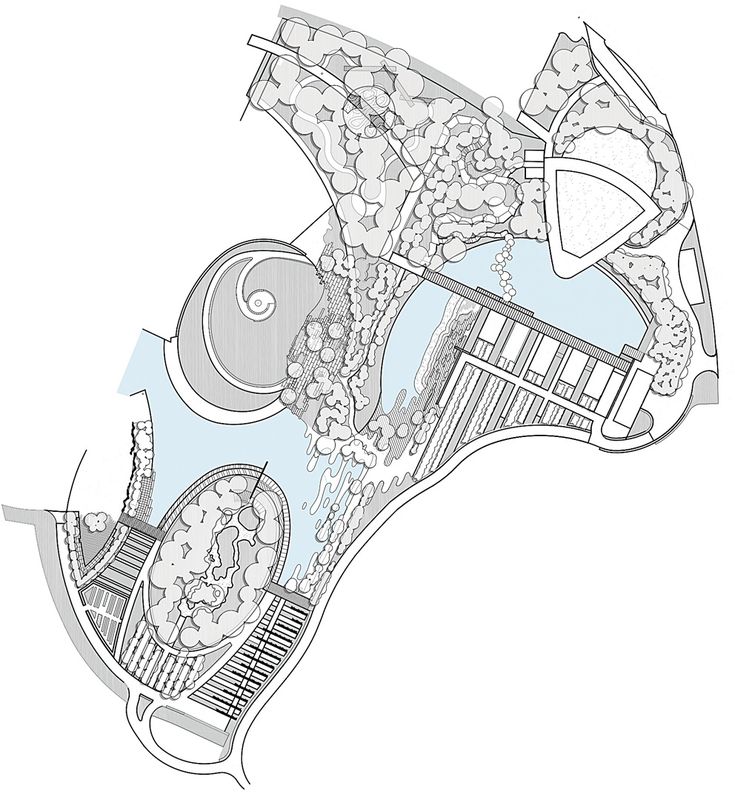

The central sand garden is an abstraction of Australia’s red, arid centre.

Image: John Gollings

If we consider the Australian Garden, it’s impossible not to think of the red sand, of that image of the red sand. It is so striking – a remarkably effective logo for the project and a direct route into the public’s affections. Promoted by the profession, too, it is the image of choice for articles and awards coverage. And this ubiquity is unfortunate. While the sand garden undoubtedly makes for an arresting image, its prominence risks reducing the entire design to a single photo opportunity.

And that gets to the nub of it. My unease is not born of some residual or unresolved cultural angst over our place in Australia’s arid landscape. Nor is it the frustration of physical exclusion from a key part of the site. It is the unease felt when meeting a place that seems to be designed so consciously and unashamedly for the lens of the eye or the camera. It’s a fine line between designing a spectacular outcome and designing for the spectacle, and in a fabulously reproducible image, a marketer’s dream, it’s easy to see spectacle, along with the necessary stasis. There can be no growth or senescence left unchecked. And you don’t even have to enter the garden to capture the shot; you can lunch in the cafe and enjoy the view, hopefully with the brilliant blue or stormy black skies that set off the red so perfectly. As a further complication, the viewer is centred and elevated – positioned at the perfect angle for the colonizing gaze, surveying its conquered domain. Intent or not, it’s a matter of reception: people make of our work what they will.

While I don’t mean to suggest that this is all there is to the red sand garden, it the source of my discomfort. We know our world in large part through images; for better or worse this image of the red sand is the Australian Garden’s most reproduced. And stasis is its inherent condition. That is the dilemma the iconic image presents.

The central sand garden is an abstraction of Australia’s red, arid centre.

Image: John Gollings

And yet the sand garden is beautiful. Beautiful in form, in the forms it evokes – the stillness and activity of the desert, sparse and yet packed with life.

Contemporary landscape architecture has a fraught relationship with beauty and the notion of aesthetics, both of which are too readily equated with the scenic for comfort. Grounded in rational Cartesian thinking and the picturesque, played out through McHargian design strategies, and returned to via landscape urbanism (to gloss over recent history) is an endlessly recurring professional debate where beauty and the “aesthetic,” central as they are, are relegated to the status of the embarrassing uncle at Christmas and avoided in polite circles. This is an unfortunate state of affairs, but then process has been a fine replacement. Ecological, or other, process defies stasis. So how are we to reconcile the undeniable beauty of the red sand garden, unchanging, as it must be, with the process we see around it as the larger garden matures?

Perhaps this is beside the point. The red sand garden, the pivot of the site, might simply be the hook drawing us into the story of our relationship with our flora. From artist Peter Walker’s strategies of pattern, seriality and gesture, through to the eco-revelatory, there is a strong and diverse lineage of using aesthetic or cultural references to frame the conversation that matters to designers. As Elizabeth K. Meyer says of the sand garden, “It operates as a datum of orientation and disorientation…”1 To suggest that the sand garden is only an image, an abstraction of the red centre, is to deny its power. The red sand structures the site and circulation more than an inaccessible part of the site might be expected to. It centres both the design, and its cultural impact, reflecting our physical and psychic place on the fringe of the arid centre. My earlier doubts are more than matched – in Meyer’s words, “My initial reading of the centre as a symbol, or a sculpture, or perhaps a scenic view but not experience, can no longer be sustained.”2 I envy the first-time-visitor’s eyes where stasis marks a manipulated and cultivated landscape, and the maturation of the surrounding stage 1 gardens only makes the contrast greater.

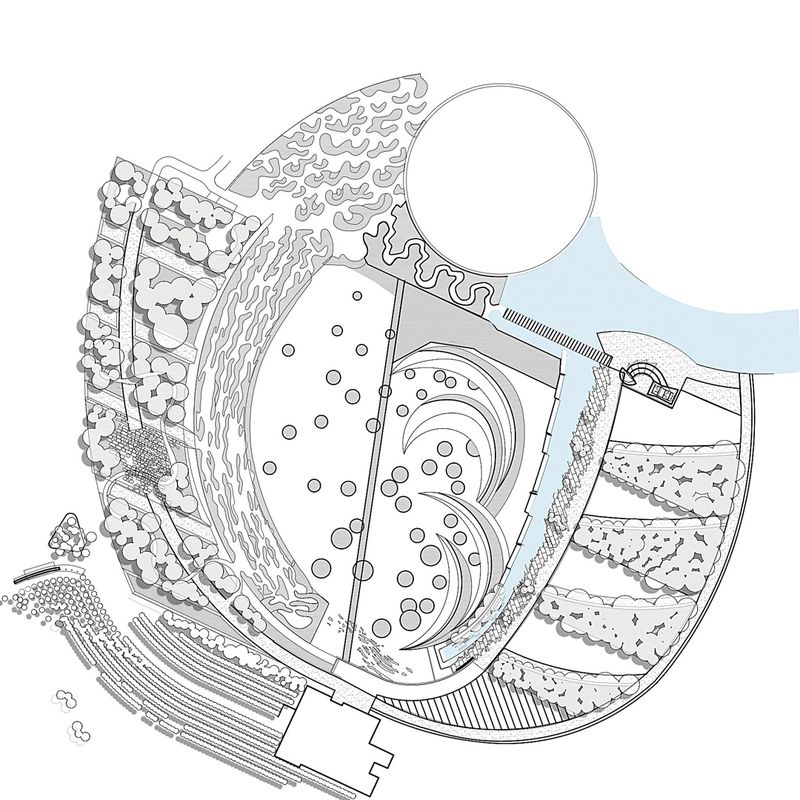

A curved pathway leads to the summit of an artificial hill, which offers spectacular views of the gardens.

Image: John Gollings

When circling around the red centre of stage 1, its meaning is made clear to me by the tension between our exclusion from that centre and the many invitations to engage with it. It provokes a questioning of our assumptions; about what a botanic garden is, familiar stories of settlement and urban life, our ways of inhabiting the land. But the sand garden isn’t the whole garden. The rock pool walk, with its sculpted escarpment and banded plantings, becomes more inviting with every visit; and the eucalypt walk, its artfully laid stonework now softening further with vegetation, has always delighted. In both areas the red sand is a formidable presence, whether as the back of a lunette integral to the form of the escarpment, or viewed through a dappling fringe of leaves. Yet even though we use the red centre to define ourselves to others, it is only a part of the story.

Stage 2 has a different focus and orientation. Here, water takes centre stage and the contrasts used to such effect in the earlier stage are not so evident. The visual absence of the red sand is certainly felt. The alternating lack and abundance of water plays out with the “weird and wonderful” garden, but the stonework, so prominent here, lacks the finesse so noticeable in the eucalypt walk. Perhaps it’s the immaturity of the plantings, but stage 2 seems to lack the subtlety of stage 1, and it’s difficult to see it equalling earlier successes. The “temporary” gardens in stage 1 (arguably the least successful in a design sense, despite their programmatic intent) are extended in stage 2 with themed “greening,” “lifestyle” and “backyard” plots using garden show strategies. The arbour garden should be interesting, but currently isn’t. Encouraging the domestic use of indigenous plants is admirable, and should be approached creatively, but these areas lack the edge evident in the rest of the garden. Any narrative inscribed in a garden should be leavened with pleasure. The earlier section not only succeeds in creating meaning (and distilling national narratives is no small success), it does so in a bodily, sensory way. The experience is the meaning. This is not yet true of stage 2.

Fundamentally, what distinguishes art from craft is the capacity of the former to provoke, to invite the viewer to engage and participate in an intellectual journey. Just as some artwork seeks to go beyond passive viewing to invoke the bodily experience of the viewer, the Australian Garden sets out to engage at a sensory level, but beyond that to provoke at the level of experience. It is a bold, grand cultural gesture, crafted from the familiar materials we all use. It has successes and perhaps some failures. To me, the joy of landscape architecture is that it lies at the intersection of art and craft. And the Australian Garden is one perfect illustration of this. Complex, conflicting, exciting, evocative, problematic, beautiful – isn’t this what art is?

1 Gini Lee and SueAnne Ware [eds] , Taylor Cullity Lethlean: Making Sense of Landscape (Washington DC: Spacemaker Press, 2013), p 62.

2 Ibid., p 60.

Credits

- Project

- The Australian Garden

- Landscape architect

- TCL

Australia

- Project Team

- Perry Lethlean, Kate Cullity, Taylor Cullity Lethlean team

- Consultants

-

Architecture

Kerstin Thompson Architects, Gregory Burgess Architects, BKK Architects

Art and sculpture Mark Stoner & Edwina Kearney, Greg Clark

Cost planner Donald Cant Watts Corke, Rider Levett Bucknall – Melbourne

Engineering Meinhardt, Irwinconsult, Felicetti

Horticulture Paul Thompson

Irrigation Irrigation Design Consultants

Lighting Barry Webb and Associates

Soil consultant Robert van de Graaff, Peter May

Superintendency LIS

Water Waterforms International, Doug Basich

- Site Details

-

Location

Cranbourne,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Construction 24 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens

Source

Review

Published online: 3 May 2016

Words:

Kate Gamble

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2014