In 2001 JMD Design (then Anton James Design) won an international competition to design Mt Penang Gardens, a eight-hectare park in Kariong, on the New South Wales Central Coast. At the time public landscape commissions were expected to celebrate and define Australianness and, especially in Sydney, the legacy of the Sydney Bush School. At Mt Penang, however, JMD Design director Anton James was able to reinvent this garden cannon without acquiescing to literal and didactic landscape approaches. Mt Penang Gardens opened in 2003 and, in recognition of its recent tenth anniversary, this piece highlights some of James’s enduring and quite radical contributions to public gardens.

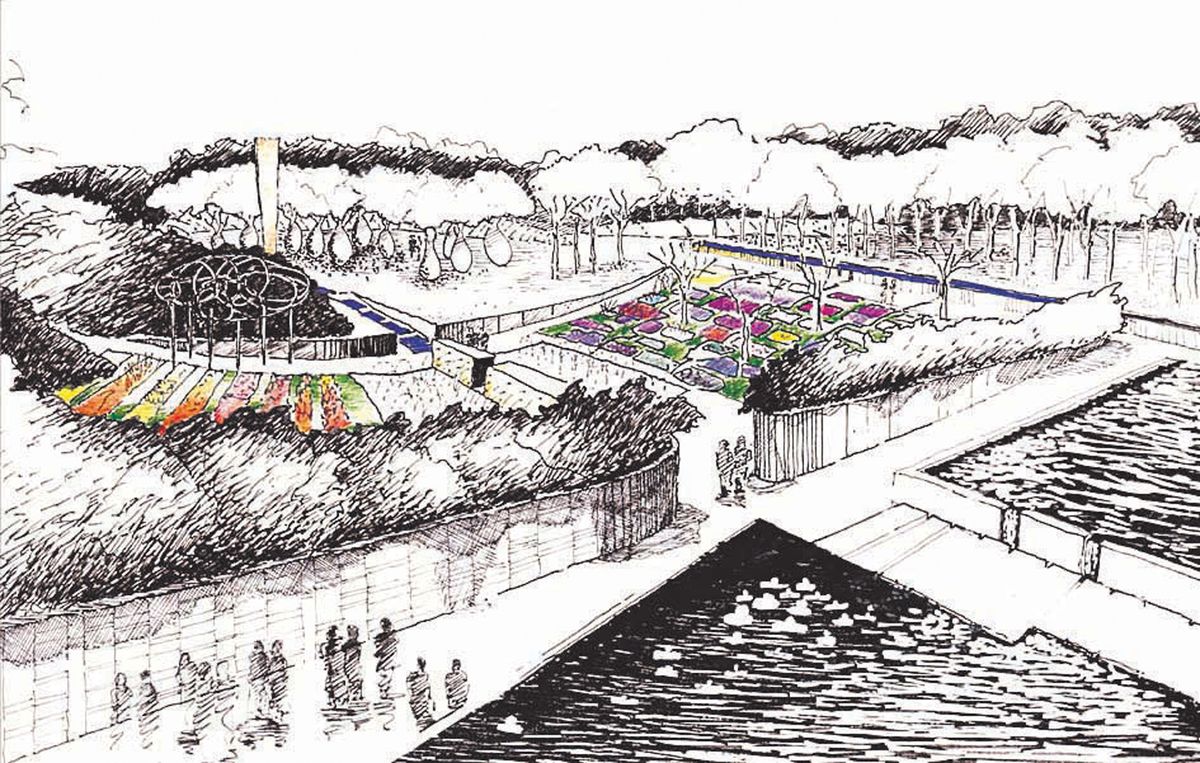

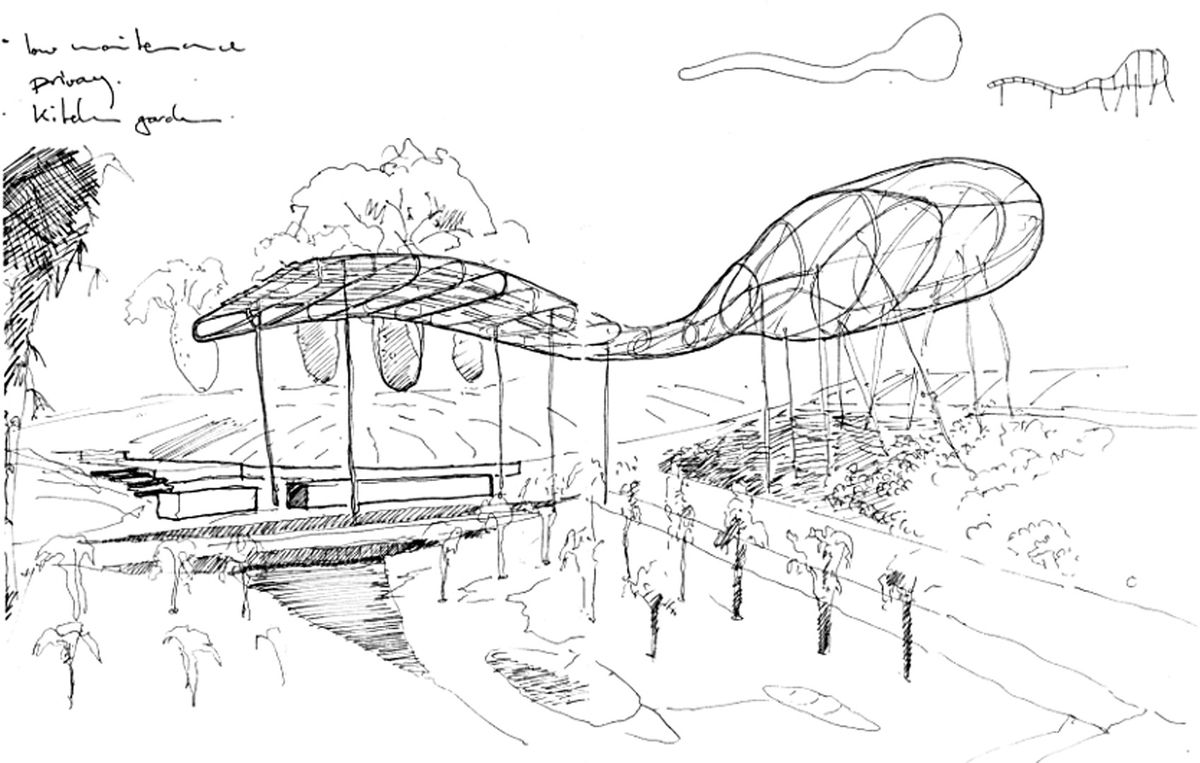

The design of Mt Penang Gardens is deceptively simple – a raised plateau comprising twelve garden rooms, some incised, some embossed, set in a former hanging swamp or water garden. The plateau is both an organizing framework for the whole of the garden and a tectonic, abstract expression of the region’s sandstone plateau landscape. When I first saw the plan, before visiting the site, I couldn’t help but think of the pie floaters from the famous Harry’s Cafe de Wheels in Woolloomooloo. Little did I know then that this landscape floats both literally and metaphorically. After winning the competition, James was informed that the City of Gosford’s water supply pipeline bisects the middle of the garden and cannot be built upon. This forced an inversion of the original scheme. The design transformed from a large, square plateau with an organic fissure cut into its sides, into an irregular plateau that avoids the easement while providing a large internal gathering space, with geometric fissures incised into its edges. The haphazard and irregular overflow from the existing dam, which had previously created a scoured channel, evolved into a key element – the water garden. Since James’s characteristic approach to most design impediments is to turn site challenges into opportunities, the result is a series of highly sculpted tectonic moves and a water garden that cradles a series of interior gardens. The water garden both sequesters and seamlessly joins the interior gardens to their context.

The water garden both sequesters and seamlessly joins the interior gardens to their context.

Image: Brett Boardman

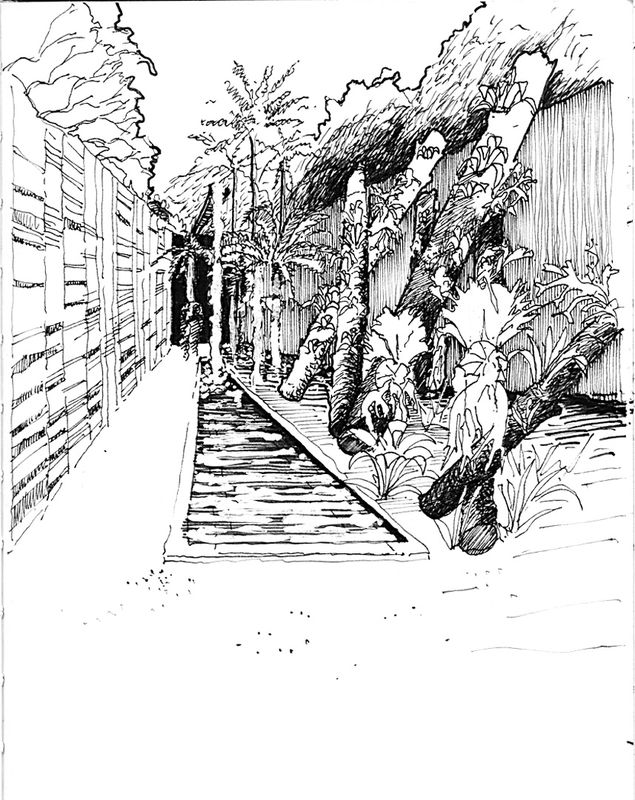

As I entered the garden across a bridge inspired by a fallen log, I expected to feel as if I was entering an island. This experience, however, felt more solid, less precarious and much more sculptural than that. And because of the spatial sequences, the flatness of the weir water and the robust scale of its dam, I found I was walking on and within the water garden. The experience was less a crossing over a watery surface and more a wading through. While the top of the plateau offers a series of “rooms,” careful choreography and a cacophony of juxtapositions mean there is no clear or singular path. You wander and you explore, sometimes immersed in these rooms, sometimes on vantage points straddled between them. James’s breach with the normative approach to the Australian garden – linear, sequential and interpretative – is radical. The form of the plateau’s gardens is organic, hosting a variety of plant settings and a series of designated spaces for curated temporary gardens. The plateau exterior is resolutely over-scaled and its level drops dramatically but the scale of its inner spaces is varied, with the mostly intimate and internalized an example of James’s “garden-within-a-garden” tactic. While this can be seen as very much a part of the public garden tradition, there is yet another well-considered twist at play here.

Each of the garden rooms has distinct flora, materiality and spatiality; however, it is the physical microclimates that the rooms embody that are most striking. They inspire curiosity and evoke haptic responses to their species’ collections, rather than a scenographic diorama landscape. The planting design creates ethereal spaces and its composition avoids pitting native against exotic. Rather, it allows colonization and shows how vegetation takes advantage of, and creates, various microclimatic conditions to develop resilience. This artifice and the careful crafting of spatial volumes contrasts with the propensity of plant materials to thrive, survive or die. The regimes of care produce an understated landscape that is less manicured – at once feral but contained and, as it must be, in a constant state of becoming. Visitors must wander through and discover this for themselves, responding to the artful juxtaposition of geometries and contexts.

The water stair as photographed in 2005.

Image: Brett Boardman

Such complexity is increased by large incisions into the plateau’s edge where fissure gardens provide opportunities for a greater diversity of species. While the planting framework for the plateau’s surface is primarily native Sydney sandstone species, these gardens enclose specialized plantings, both native and exotic. The plateau gardens are theatrical. Pathways turn back upon themselves, widths and materials change, all to choreograph the visitors’ meandering course and direct attention to physical and material differences such as rich textures, light and shade, rather than suggest a cohesive narrative. There are spectacular moments of serendipity such as the glimpses through the bottle tree garden to the puddle fountain with a sculptural cloud beyond, a combination suggesting an activated Yves Brunier collage. Conversely, the fissure gardens are a contemporary expression of traditional grotto landscapes, carved out, internalized, and complete with floating staircases, epiphytes and tree ferns. While vaguely reminiscent of Victorian collector gardens, these lack their typical self-consciousness. The fissure gardens are at once hidden yet exposed, closed to the plateau above yet open to their wider surroundings. So while the plateau’s surface gardens overlap and are somewhat inward-looking, the fissure gardens, despite being spatially sunken, look outwards across the water gardens to the surrounding landscape. And although the water garden suggests the site boundary, remnant bloodwood and scribbly gum bushland are encouraged to colonize its western parts.

Mt Penang Gardens captures the paradoxical nature of public gardens in Australia. By cleverly juxtaposing disparate identities it avoids the normally clear identity suggested by established typologies and nationalist narratives. Its engineered – almost infrastructural – landscape contrasts with its bushland context and wider topographies. In scale with that context, it is nonetheless foreign to it. Abstract gestures and tectonic volumes collide with specific spaces for and of particular plants. Garden traditions are strangely familiar yet subverted and made anew. Willingly, it accepts garden ideas as diverse as the populist festival, the floral exposition and those of the Sydney Bush School, yet here, none are condemned to their usual conventions. It could even be said they are set free. The open choreography and cacophony of the path system allows for serendipity and unexpected spatial juxtapositions. More than ten years on, Mt Penang defines and explores a more contemporary cannon in which Australian landscape identity is less about vexed questions of native versus exotic, naturalist versus formalist, and more about accepting and celebrating otherness. James’s masterful public garden provides a much-needed design alternative that explores and expresses emergence, resilience and adaptation in landscape form.

Author’s Note: I am indebted to my close friend and colleague Professor Gini Lee for acquainting me with notions of “strangely familiar.” While the strangely familiar often refers to ordinary and everyday landscapes or situations, in the context of this article I use it to aptly describe garden typologies that JMD Design transforms and subverts.

Credits

- Project

- Mount Penang Gardens

- Practice

- JMD Design

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Anton James, Ingrid Mather, Geoffrey Britton, Craig Burton, David Duncan, Diana Pringle, Romily Davies, Jenny Clarsen, Matthew O’Connor

- Consultants

-

Architecture

Lacoste + Stevenson Architects

Construction Haslin Constructions

Engineering ACOR

Quantity surveyor Altus Page Kirkland

Structural engineer Professor Max Irvine

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2003

Design, documentation 18 months

Construction 12 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens, Parks, Public / civic

Source

Review

Published online: 3 May 2016

Words:

Sueanne Ware

Images:

Anton James,

Brett Boardman

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2014