1. Uniting a landscape of fragmentation

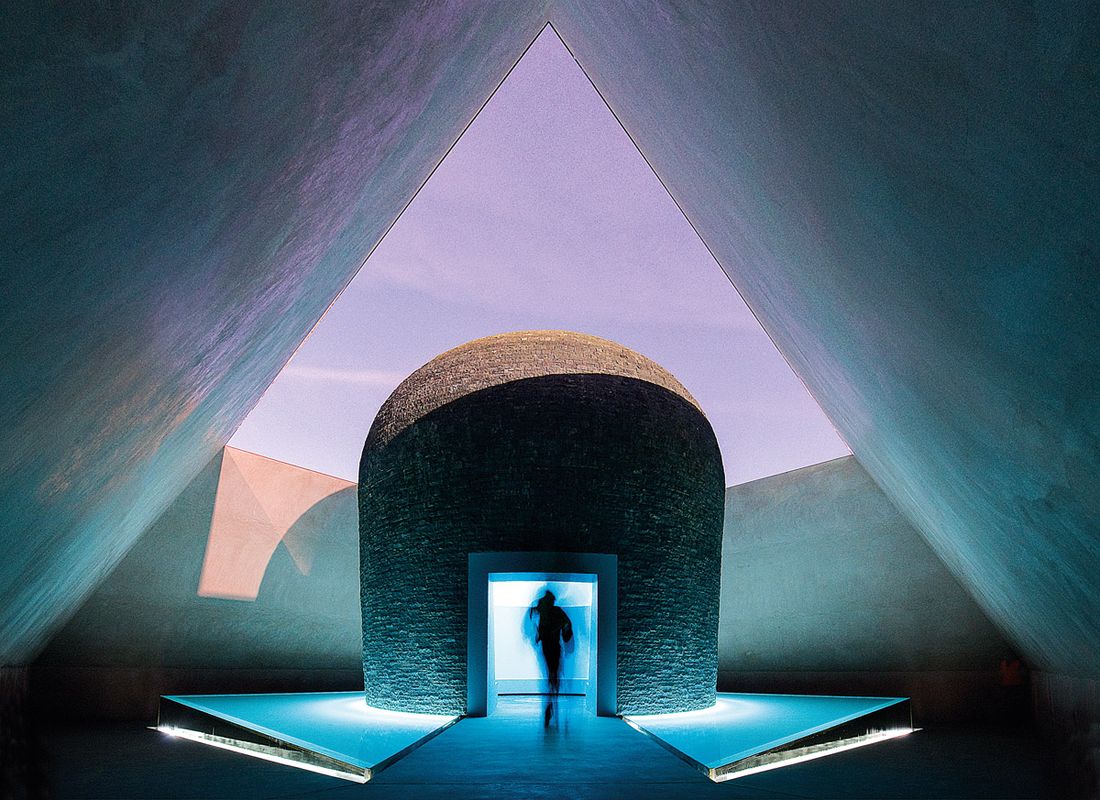

The National Gallery of Australia’s newest garden, the Australian Garden, keeps with the original plan for the precinct, with a world-class sculpture by James Turrell adding a focal point.

A stone pathway leads to the skyspace sculpture.

Image: Christian Borchert

The sculpture garden at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) is one of this country’s most iconic exemplars of landscape architecture. Commissioned in 1978, landscape architects Harry Howard and Associates (HHA) conceived the garden in concert with their wider, collective vision for the NGA and the adjacent High Court of Australia (HCA). Architects Edwards Madigan Torzillo Briggs (EMTB) similarly envisaged the buildings as a monolithic ensemble and their brutalist concrete edifices respond aptly in scale and proportion to their expansive, if not vacuous, Parliamentary Triangle setting.

For HHA, the buildings’ fifteen-hectare surrounds were to be “unashamedly Australian, where built elements would be seen within and against a backdrop of indigenous and other vegetation of the continent.” Uniting architecture with landscape, EMTB structured the precinct by projecting the plan geometry of the building’s equilateral triangle module – within and overlaying this triangular template, pathways, undulating earthworks and terrace platforms were set out in proportional accordance with antique golden mean measure. The three-hectare area reserved for sculptural display is spatially organized into a series of interconnected out-of-doors “galleries” arrayed along an axial spine called The Avenue. Along with the concern for using Australian and indigenous Canberra species, seasonal cycles informed the planting.

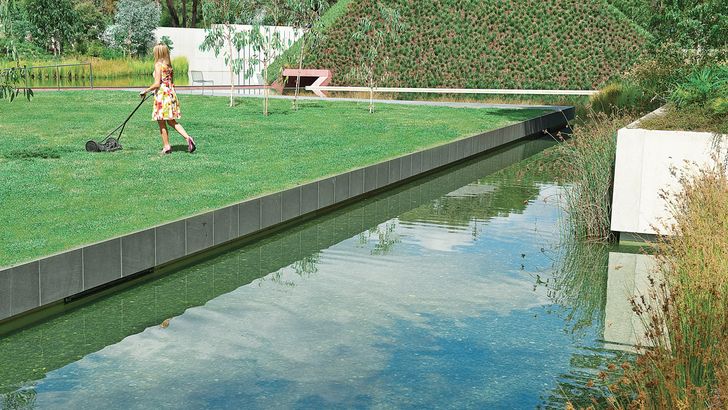

NGA visitors enjoy the upper lawn of the Australian garden.

Image: Christian Borchert

Experiencing the garden episodically, the visitor’s journey originates at the Winter Garden forecourt, progresses to the Spring Garden at Lake Burley Griffin’s edge and concludes with an arrival at the Summer Garden. This truncated sequence, however, is by default. The Autumn Garden (along with other components such as an amphitheatre) was never realized. Within each out-of-doors gallery, botanical colour and sequential bloom periods register seasonal dynamics. Sculptures are positioned so as to be viewed through a veil of casuarina sprays and other foliate frames. Dappled with pools of sunlight and shadow, the galleries’ open floors, paved with slate or more tactile crushed rock, facilitate fluid movement around the artworks.

Water is also an essential element. In the Winter Garden, for instance, a formal pool offers a placid, reflective setting for sculpture. Similarly, a “marsh pond,” one component within an abstract riverine system, is the Summer Garden’s focus. This garden also once featured a triangular, faceted rill and water wall; these architectonic constructions, however, have been waterless and derelict for years, camouflaged by an apparently permanent “temporary” restaurant marquee. Today, the patina lent by the now mature plantings, together with maintenance that seems sporadic at best, has obscured appreciation of the garden’s crystalline structure. Since officially opening nearly thirty years ago, the sculpture garden has attracted heritage status. More importantly, it now functions effectively as a public park; unlike the Parliamentary Triangle’s “magnificent distances,” the garden is more humane and intimately scaled. It also remains no less a touchstone for those in pursuit of an Australian design ethos. Landscapes, however, are dynamic and the NGA’s environs have recently gained a pair of remarkable new additions, each coming as adjuncts to gallery expansions.

Aerial view of the skyspace sculpture.

Image: Christian Borchert

The first new landscape addition began in 1996. That year, the NGA commissioned Australian artist Fiona Hall to design a garden to occupy a courtyard created with the construction of a new exhibition wing. Departing from HHA’s Summer Garden and traversing the Autumn Garden’s intended site, now a car park, Hall’s Fern Garden is accessed from what could easily be mistaken for a service laneway. At the pathway’s terminus, one surreally encounters not rubbish bins, but the entry to Hall’s garden – a wrought-steel gate embellished with a representation of the female reproductive system. Taking its cue from the form of unfolding fern fronds, Hall’s garden features a rhythmically spiralling pathway which wraps around a central fountain. Across this vortex, fifty-eight-centuries-old Dicksonia antarctica tree ferns are planted on a grid. Through texts set within the pebbled paving and inscribed on granite benches, the garden references not only indigenous nature, but also Indigenous culture. Ultimately, however, this elegant garden is more often experienced only visually, through glass from within the gallery itself.

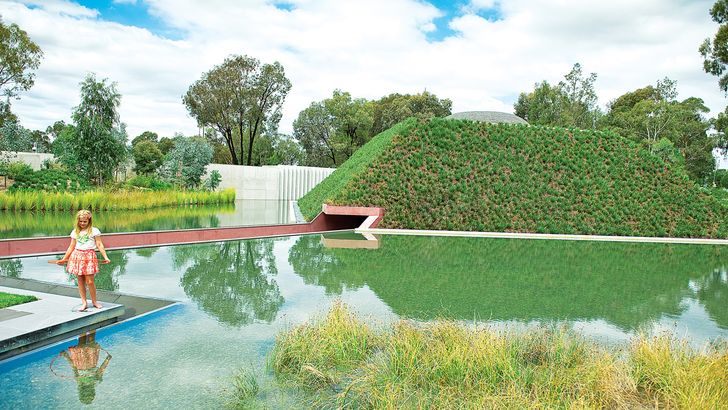

The NGA’s most recent landscape addition is the Australian Garden, which opened last October. In a rare reversal of convention, a garden “paradise” has usurped a large portion of the gallery’s “parking lot” (ironically, a component of HHA’s first plan). Like Hall’s Fern Garden, the Australian Garden was an adjunct to a new gallery extension, this one to showcase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art.

The garden’s lawn terraces.

Image: Christian Borchert

Designed by landscape architects McGregor Coxall, the new garden is, foremost and laudably, in keeping with the spirit of HHA’s original plan for the precinct. Reapplying EMTB and HHA’s technique, for instance, McGregor Coxall organized the new garden using the golden mean and a triangular grid, accordingly aligning pathways, bridges, walls and pools. McGregor Coxall supplemented the site’s mature eucalyptus trees (outcomes from HHA’s earlier initiative) with new plantings of, like their predecessor’s choice, species indigenous to the Canberra region.

The new entry to the gallery presents itself openly to King Edward Terrace.

Image: John Gollings

Set within a large pool, American artist James Turrell’s “Skyspace” sculpture, Within Without, is the garden’s focal point. The skyspace is entered by descending a ramp through the pool’s mirrored, aqueous surface. Within the space is a large, square-based pyramid with soft red ochre interior walls. A stupa, finely crafted of Victorian basalt, rises at the centre, accentuated by turquoise water. The stupa accommodates a domed viewing chamber, open to the sky above. A moonstone, set into the centre of the floor, mirrors the oculus overhead. Within this chamber, according to the NGA, “light seems more painterly; movement and sound are intensified, the sky shimmers and pulsates.” Turrell’s installation is without doubt a world-class attraction. To appreciate its elegance and sophistication, one need only compare it to the “Ned Kelly armour-esque” camera obscura in the National Museum of Australia’s nearby garden. As with Turrell’s skyspace, detailing throughout the garden is exquisite and finely crafted. Far removed from mere cosmetic “landscaping,” the Australian Garden is of greater visual character than its benign, if not banal, controversial backdrop: the “cyborg” gallery extension.

After experiencing Turrell’s breathtaking Within Without, I renegotiated the fractured landscape labyrinth enveloping the NGA and made a return visit to HHA’s sculpture garden. There, at least for me, an aura of melancholic decay was palpable, despite last year’s installation of a life-sized, cast-iron maquette of Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North on the central axis. The NGA is now the locus of three nationally significant gardens, along with lingering relics of HHA’s overall NGA/HCA plan. Perhaps the NGA could even follow its own newly established precedent and relinquish more of its car park to at last realize HHA’s Autumn Garden? Regardless, it is timely to now consider the NGA’s surrounds as a cohesive whole, to unite this landscape of fragmentation.

—Christopher Vernon

2. New work in a new context

McGregor Coxall’s additions to the NGA aim to pay homage to Col Madigan’s and Christopher Kringas’s geometric order. But does it accomplish this?

For any landscape architect the challenge to extend a work of such accomplishment and significance as the gardens and broader landscape setting of the National Gallery of Australia is a daunting prospect. McGregor Coxall has nevertheless been confident in its design response as landscape consultant for the new Australian Garden. This important project is associated with the new entrance and gallery facilities designed by Andrew Andersons of PTW and opened in September 2010. The project has been steeped in controversy, with valid questions raised about the integrity of the original project and the matter of moral rights.

Celebrating the traditions of the Australian backyard set in the new garden.

Image: Simon Grimmett

The landscape associated with the original building is a seminal work by Harry Howard and Associates, notable for its sculpture garden, which is a sensitive integration of architecture and landscape, moderating, humanizing and celebrating Col Madigan’s and Christopher Kringas’s (of Edwards Madigan Torzillo Briggs) heroic brutalist architecture. The artistry of the sculpture garden is evident in the manner in which it engages the triangulated geometry in an understated yet profound way. This garden is an exemplar of its era, an exploration of an authentic national identity engaging respectful interpretations of pre-existing landscapes and a skilled use of indigenous planting.

In positioning their work, McGregor Coxall sought to pay homage to Madigan’s geometric order. While an analytic drawing overlay demonstrates how a triangulated system of interlocking patterns has determined the location of some key elements, this well-intended yet tenuous contribution to the landscape experience results in some awkward geometric relationships.

Celebrating the traditions of the Australian backyard set in the new garden.

Image: Simon Grimmett

More evident is the intent to “present a unified legible, accessible public face to the NGA.” Embracing the more orthogonal geometry of the new extension, a more surface-based geometry is expressed through a composition of clearly articulated and defined landscape “rooms.” Two planar lawns are defined by subtle changes of level and surrounded by water or wetlands. The architectural nature of these spaces is accentuated by the use of bridge-like elements that provide access and thresholds distinctly expressed by the geometric shifts.

Given the clear positioning of the architecture as a departure from the spirit of the original work, an extension of the character of the earlier landscape – however tempting – would have compromised and indeed diminished the value of the Howard landscape. McGregor Coxall in its own way clearly interprets the new architecture in seeking a coherency for this part, in favour of engaging the whole setting. In this they had little choice.

Celebrating the traditions of the Australian backyard set in the new garden.

Image: Simon Grimmett

Rather than debating the rights or wrongs of this positioning of the architecture – as problematic as it is – the most useful task is to assess the value of this new work within this distinctly new context. Does it contribute to the legibility of the new entrance? Does it integrate with the new galleries? And importantly, does it provide a contemporary “Australian” experience, and how does it engage with the larger setting?

The new landscape embodies a “relaxed formalism,” with a planar composition, structured circulation, fine and elegant detailing, spare materiality, skilled use of indigenous plants, careful management and recycling of water, as well as a subtle integration of existing trees. All this demonstrates the high degree of design dexterity and accomplishment that has come to be expected in the work of McGregor Coxall.

Celebrating the traditions of the Australian backyard set in the new garden.

Image: Simon Grimmett

The confident engagement of the vast sculptural work by James Turrell at the eastern end of the forecourt garden invites exploration while allowing it to stand independently in the landscape – yet the intent to connect it to Madigan’s geometric determinants is less convincing. The drama of its spatial experience is cleverly accentuated by the ramp providing a descent through the seemingly suspended plane of water.

Despite these positive qualities, there are ambiguities evident in the landscape and its relation to the new architectural work. First is the matter of address and entrance. The new entrance gallery seeks to lend a formal legibility to the NGA from King Edward Terrace. Yet from this approach or from the stairs accessing the car park below, it is not clear if the experience of the new garden is to be enjoyed before or after entering the building. The generous formal promenade extending from the main entrance strangely stops short of King Edward Terrace. Similarly, there is a tenuous relationship between the eastern car park and the entry to the gallery. This results in some confusion rather than reinforcing the clarity of address. There is a similar discomfort between the main entrance and the outdoor cafe area to the west, which is disconnected from the main lobby space. The associated outdoor western terrace is raw and harsh in character, with its exposure to the adjacent roadway.

One of the most powerful aspects of the new gallery design is the serpentine path through two hundred hollow logs – “The Aboriginal Memorial” – yet an opportunity to echo this compelling emotional and spatial experience in the adjacent landscape is underplayed.

The Australian Garden at the National Gallery of Australia.

If the implied brief is to provide a contemporary or “new” Australian garden – a somewhat loaded aspiration – then what might be the clues? Is it in the reinterpretation of Indigenous cultures and landscapes, multiculturalism, or popular culture? This question seems to remain unanswered.

The formal lawns provide a pleasant outdoor setting adjacent to the major halls, yet they are disconnected from other experiences within the new addition and have a mannered, refined and rather European quality. Perhaps this is now the reality of the contemporary Australian experience. But should it be?

The ambiguity of the garden space may have been alleviated if it had been embraced as an integral part of the gallery circulation and accessed from within the building, being more defined and contained on its edges. The maturing of the landscape will certainly help in this regard.

A bigger question also relates to the role of the garden space in the broader setting of the Parliamentary Triangle. Countless schemes have been prepared over the years for this significant and symbolically loaded setting, yet there is a lack of coherence in its landscape evolution and there is a need for a more cogent dialogue between the elements, which would be aided by more intensive avenue planting on the cross axis. The saddest aspect of this is the shameful neglect evident in the forecourt to the High Court.

Madigan’s vision of a grand organizing square is in tatters and the landscape is in need of a new and meaningful vision that could provide a clearer context and unifying setting for the adjacent galleries. The demise of the design role successively of the NCDC, NCPA and NCA has left its mark on this most significant lost landscape.

Both the landscape and architecture of the new additions to the NGA provide some positive experiences with accomplished execution, yet sadly lack the conviction – however flawed – and integrity of relationship found in their predecessors. Perhaps in our current political climate achieving this is an impossible dream.

–Ken Maher

Credits

- Project

- The Australian Garden at the National Gallery of Australia

- Landscape architect

- McGregor Coxall

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Adrian McGregor, Christian Borchert, Kristina Frizen, Georg Petzold

- Consultants

-

Architect

PTW Architects

Civil engineers Cardno Young

Construction manager Manteena

Contractor Urban Contractors

Lighting George Sexton and Associates

Mechanical engineer Steensen Varming

Structural engineer Birzulis and Associates

- Site Details

-

Location

Parkes,

ACT,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 48 months

Construction 36 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Culture / arts, Outdoor / gardens

Source

Review

Published online: 28 Apr 2016

Words:

Christopher Vernon,

Ken Maher

Images:

Christian Borchert,

John Gollings,

Simon Grimmett

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2011