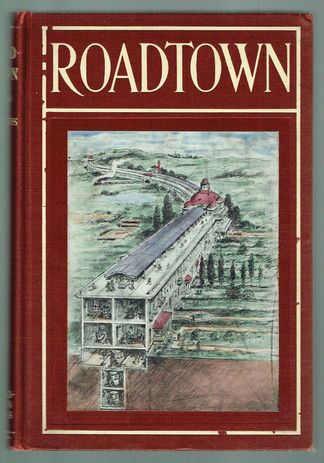

Roadtown, written and self-published by Edgar Chambless in 1910.

Image: Courtesy of Richard Neylon Rare Books

The suburban tracts and towns of New South Wales will be required to accept another 130,000 recreational boats by 2026 – that is, in addition to the 223,000 already with us.1 These craft and the SUVs that tow them are just two of several much-sought-after, highly mobile apartment accessories endangering civic amenity in Australia. Another 130,000 discretionary vessels cannot be readily housed on subdivided land already occupied by bungalows, villas and apartment blocks, many of which have dedicated off-street parking. Consequently, from Bankstown to Broken Hill there is an accelerating deforestation of established street vegetation as novice boat owners scramble to secure verge parking for their new gear. Typically, a mature paperbark is chain-sawn to a stump 400 millimetres in diameter and one metre in height – yet not removed entirely, so that the stump can serve as a useful demarcation from the neighbours’ gear. Aggregated, this informal mayhem will remove thousands of mature, mostly native street trees from across the state over the course of the next decade. The accommodation of all this casually inviting new private property on existing and future public land – dedicated street verges and footpaths – equates to 80 million cubic metres, an area equivalent to Sydney’s Centennial Park. The same applies across the continent, with the tragic loss of Mallacoota’s wetlands to new boat ramps being only the most recently noted. These days, the accumulated impact of everyone’s kit is substantial.

So what does this have to do with new apartment types? The really new apartment types will be relocatable: structures that are supplementary to Australia’s fixed housing stock. Sure, the inner-urban enclaves will continue to construct high-density flats for a specific population, but further away from the city, the masses are getting on the road most enthusiastically. Much market shaping of both the vehicle and its passengers has ensured this new collusion between living spaces and personal mobility will continue unchallenged: it is not the housing along our roads that matters any more, but the roads themselves!

Here, I want to introduce the idea of concavity as a necessity for living in cities and towns. In the historical city of Melbourne, the public realm has a civic inclusiveness achieved through generations of close settlement. In the inner-city suburbs, living in the city means living in an intimate bond with certain streets, parks and places willingly shared with others. This, I propose, is a concave relationship between town and citizen: broadly, anonymity is respected and while one is part of the crowd, there is plenty of room to move – both culturally and physically. Ideally, in a concave city, persons and encounters will fold together into a sense of belonging that is cathartic and reassuringly democratic, even classless.

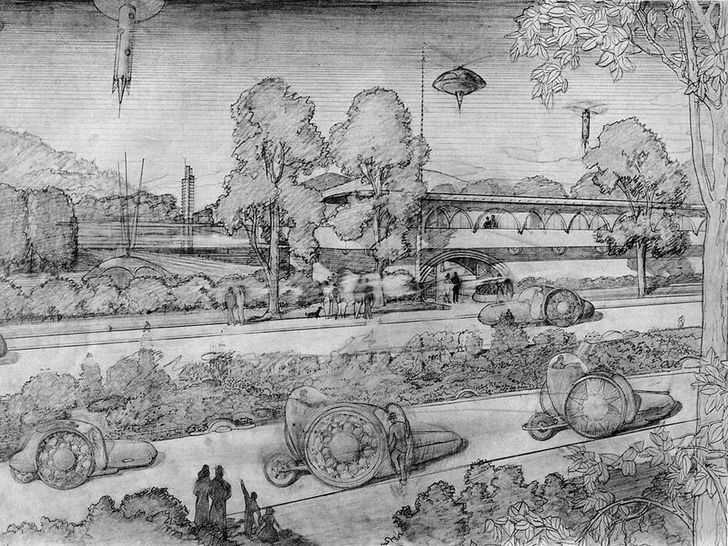

Frank Lloyd Wright sketch of Broadacre City.

Image: Kjell Olsen. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Today, our historical, concave cities and towns are under sustained assault from their nemesis, a completely new world of convex exclusion in which the public realm is crowded with persons nominally present but actually absent – existing instead in their own virtual electronic realms. Civic communality is being replaced by the anonymity of smartphones and social media: you either get out of the way (i.e. “their space”) or expect to be abused, or worse. So why cling to now-redundant civic ideals? Why seek new fixed apartment types when the quality of life on our city streets has so declined? With your every step and pause recorded by closed circuit television monitors, what is now the purpose of, for example, living in Melbourne 3000?

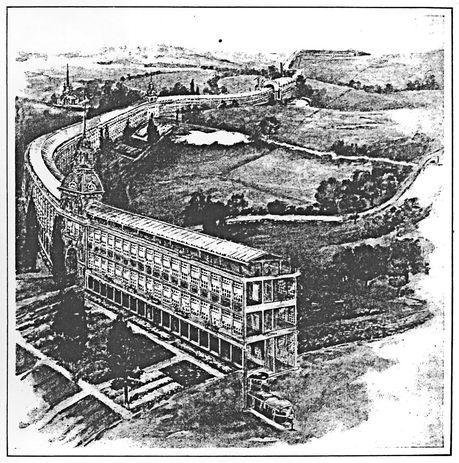

Sketch of Arturo Soria y Mata’s ciudad lineal.

Image: Arturo Soria

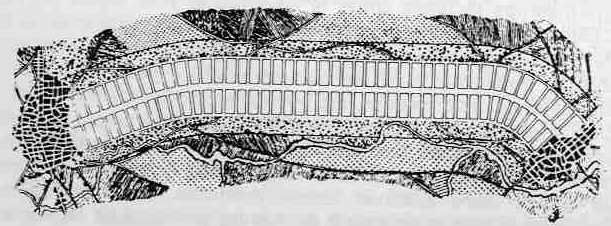

So, what’s next? It could just be Roadtown reworked. Edgar Chambless self-published this utopian proposal in 1910 and it is, surprisingly, one of the widest held architectural manifestos of the twentieth century – every major university library has a copy. But who ever read Roadtown and, more importantly, who did not? Le Corbusier took it for his Algiers plan, while Soviet architects such as Nikolay Milyutin, Ivan Leonidov and Moisei Ginzburg raided Chambless for their ultra-radical communal apartment blocks. Even Frank Lloyd Wright adapted Roadtown’s limitless transportation model for his Broadacre City. The intuition to have only one illustration – just a poorly printed perspective mounted onto the cloth-bound cover (and not even a frontispiece) – gave Chambless a continuing advantage over his rival pamphleteers: In the ciudad lineal (1882), Arturo Soria erred by copiously illustrating his not-dissimilar idea of an indefinitely extendable linear city from, say, Madrid to Moscow, while more recent admirers such as Cedric Price with his promotional Potteries Thinkbelt project (1965) demonstrated too many clever assemblies and so failed to achieve the totemic, compelling power of Chambless’s declamatory text.

Chambless’s proposal featured a uniform cross-section that combined various grades of silent monorail transportation connecting continuous and contiguous two-storey domestic apartments. The proposal included adjacent productive gardens and a communal promenade deck above, and it was all to be built in mass concrete from materials that would have been locally available. It is the sheer extent of Roadtown that sets it apart from preceding proposals for this type of “city in the country”: it could, according to Chambless, cross America from New York to San Francisco without reaching any functional threshold. That this idea is hopelessly deterministic may even be to its advantage; my copy of Roadtown carries the bookplate of Edward Albert Filene, celebrated pioneer of both credit unions and the “automatic bargain basement” – evidence that the appeal of Chambless was then, and is now, far beyond that of his worthy cooperatives. Roadtown took hold in the corporate imagination as an ideal vehicle for endless consumption: here was an endless urban construction in which everyone could have their very own powerboat, at home!

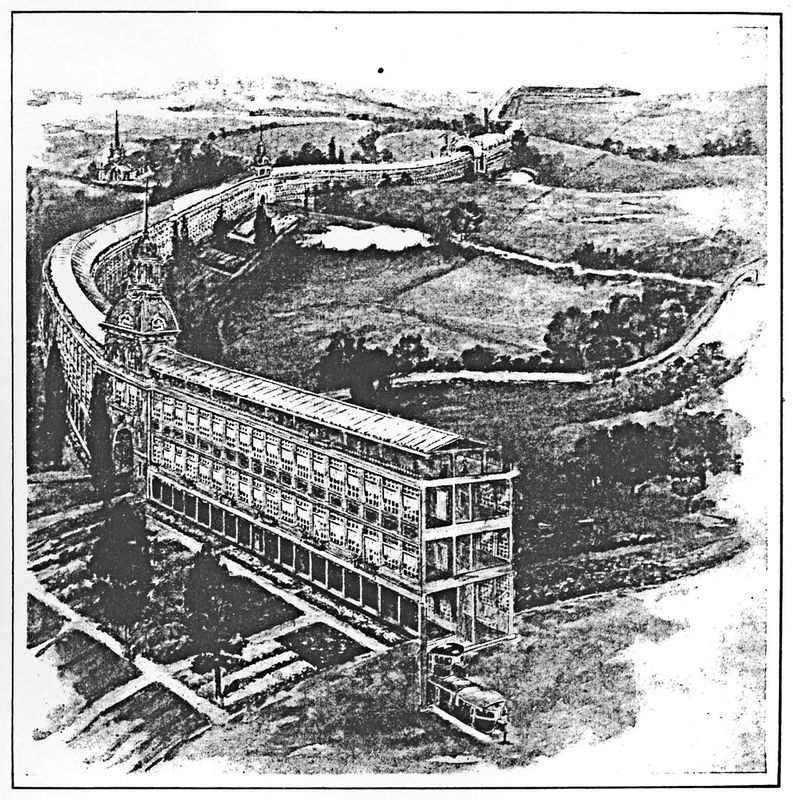

Sketch of Edgar Chambless’ Roadtown, originally published in The Independent, 1910.

Image: Milo Hastings

Chambless proclaimed: “Roadtown utilizes every utility in length which gives the maximum efficiency for that particular device.” He sought to bring the city and the country into a new and wonderful symbiosis. But just how different is this from the now almost continuous development along Australia’s regional road systems? I do not believe that these new communities are unhappy refugees from our now prohibitively expensive central urban areas – life is wildly regenerative along these “magic motorways.” The fixed suburban dwelling is about to be displaced by mobile homes equipped with any amount of plug-on supplements and sat nav support. Take a snapshot of any toll road and you will see families completely absorbed in their convex bubbles: out here, there is plenty of room to roam. The fixed, site-specific apartment house? It’s over!

In 1991, Harvard’s James Ackerman observed: “Architects and planners have not adjusted to the mobility of modern life to the extent of offering acceptable alternatives to fixed and permanent building: the mobile home, an imaginative response both to the migratory character of a large segment of our population and to the demand for inexpensive mass-produced single-family shelter, is scorned by the architectural profession and its design left to the market-research process that determines the style of automobiles. The result is that the environment is marred rather than enhanced by a type of structure destined to cover the land.”2

Ten years ago, I taught a graduate master’s studio at Cornell and, to the school’s surprise, I nominated trailer parks as our studio project. Unflappable, the university hired a bus and driver for the duration of the studio and off we went. Our enquiring group of international students was amazed at the conditions we found hidden from the highway by dense landscape planting: perfectly maintained civic spaces, carefully tended productive gardens, no fences and every lovingly kept trailer home poised on inflated tyres in preparation for a quick exit. Each student prepared a proposal for persons in a similar situation in their home country and their resulting designs were astonishingly varied and ingenious and, best of all, inclusive. For those fourteen students, it was a long-overdue circuit-breaker from the usual Ivy League fare of prestigious design projects and they returned to places such as Shanghai or Kolkata confident that they could help to build a better world.Today, we are confronted by the harsh reality of Ackerman’s injunction: a highly mobile society with plenty of “preferred outcomes” to pursue and a studied indifference among architects and, worse, our universities, to this huge but not intractable social problem in which millions of Australians desperately need well-considered, affordable and, yes, relocatable housing. If a large, modular sawmill can be dismantled and relocated within a few weeks, surely we can find an architectural alternative to the long-stay caravan park that allows us to live and work with ready access to the landscape.

But this is all a long way from Barangaroo, and getting harder and further every day.

1. New South Wales Government, NSW Boat Ownership and Storage: Growth Forecasts

to 2026, July 2010, 6.

2. James S. Ackerman, Distance Points: Essays in Theory and Renaissance Art and Architecture, MIT Press (Cambridge MA, 1991), 28.

Source

Practice

Published online: 29 Apr 2016

Words:

Peter Myers

Images:

John Tanner © Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia),

Kjell Olsen. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.,

Milo Hastings

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2014