On Australia Day 2010 the resident population of Australia was 22,130,912. Australia’s population is currently increasing at the rate of one person every one minute and eleven seconds. Although the media has mainly been using a figure of thirty-five million, the Australian Bureau of Statistics forecasts that by 2056 Australia’s population could reach 42.5 million. Either way the infrastructure, housing, work and social opportunities that define Australia’s current quality of life will need to be doubled in just four decades. The Australian dream of a house and garden in a suburban milieu has never been in greater demand and its sustainability never more tenuous.

Since 1788 Australia has always grown rapidly. Although in the past this was associated with progress, it’s now being associated with crisis. Indeed, nothing can grow forever.

While scientists have largely given up on finding a precise carrying capacity for this big brown land, in 2002 the CSIRO concluded that Australia could sustain fifty million people – that is, fifty million leading what was referred to as a “moderate lifestyle.” But Australians are not moderate; we have one of the highest ecological footprints on the planet. That means it takes five times as much stuff to sustain one Australian as it does the average world citizen. To put it another way, if everyone lived the way we do we’d need five earths to plunder. So who’s going to tell the Chinese, the Indians and the Africans that they can’t have the quality of life we take for granted? This century’s biggest issue will be about how to lift billions of people out of poverty and do so with just one planet.

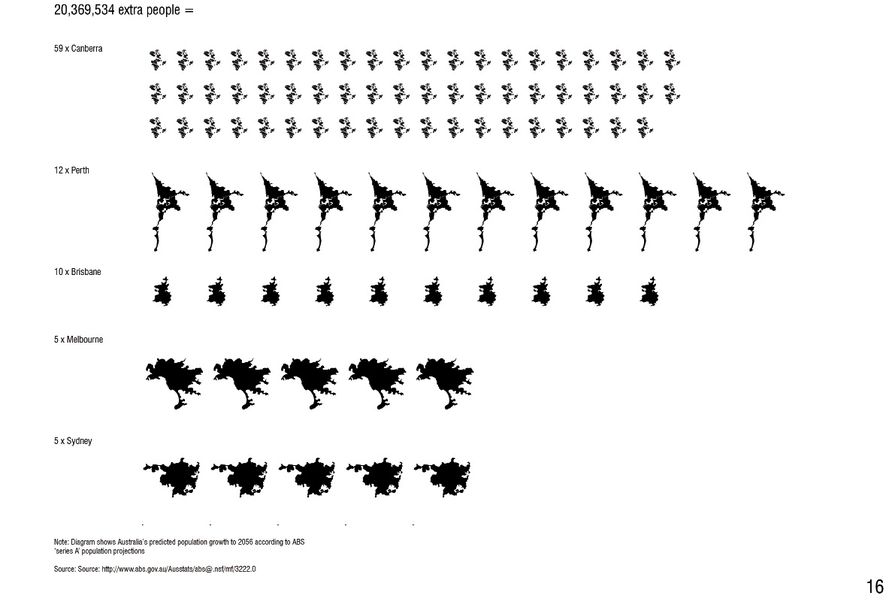

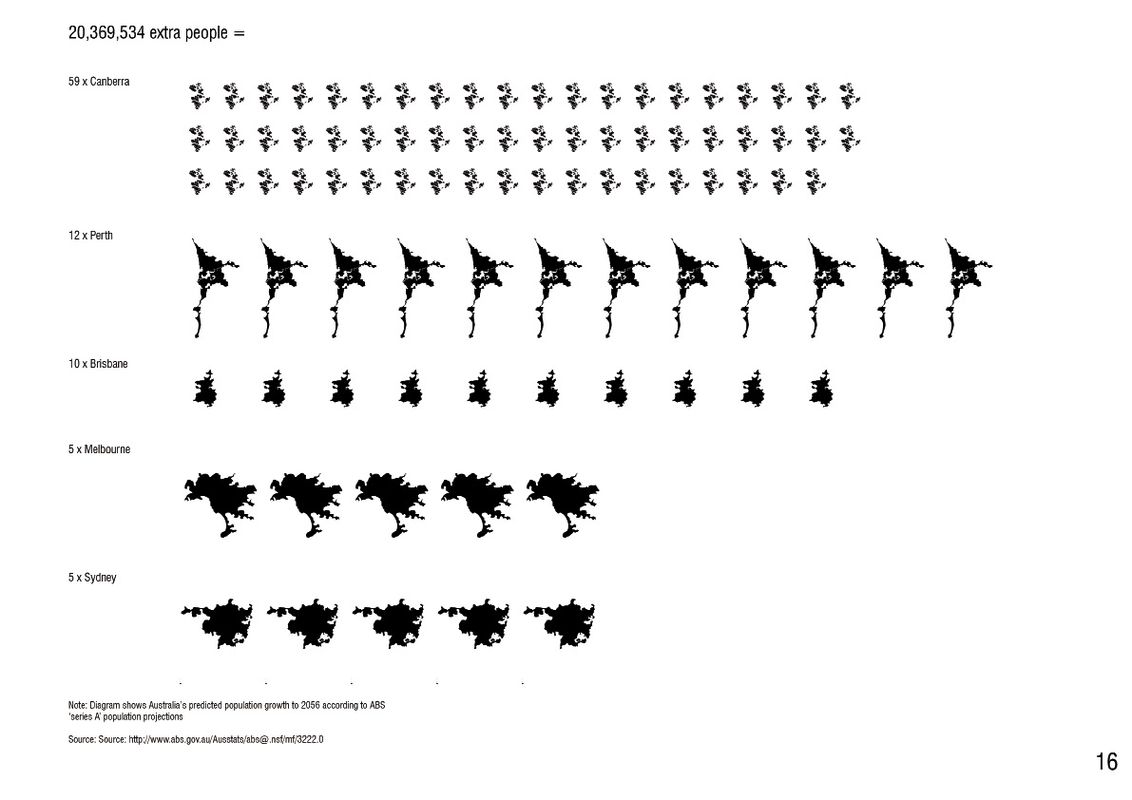

Due to urbanization the global population is predicted to stabilize mid century at around 9.5 billion people. In that context, Australia’s predicted growth from twenty-two million to thirty-five or even fifty million people appears relatively trivial. But of course, it isn’t. For the population to double in just four decades means enormous development. It means we need to build one Sydney or one Melbourne every decade between now and 2060 (Figure 1).

Although the former Rudd Government, through the Council of Australian Governments, made a start, there remains no coordinated, national planning for this kind of growth. Australian cities and towns have largely ignored the issue of where and how such large numbers of people will live. Our cities have simply sprawled, under the radar. But now things are different. As Secretary to the Treasury Dr Ken Henry asked in 2009 in response to Rudd’s “Big Australia,” “Where will these (extra) people live – in our current major cities and regional centres, or in cities we haven’t even started to build?” The answer is probably all of the above.

While Australia feels like a big country, it has real limitations. Only 10 percent of it is arable and it’s the driest place on earth. Australia currently feeds fifty million people, but to do so whole bio regions have been converted to monocultures reliant upon over two million tonnes of fertilizer per annum. There are untapped resources in the north but it’s hard to get these resources to southern populations. In the south, the Murray-Darling is in a state of palliative care and the West Australian wheat belt is suffering salination.

These landscapes are likely to come under even greater stress as places like Australia will be expected to increase, not decrease, yields so as to help feed a global population of 9.5 billion, a billion of whom are currently malnourished. As Australia gets hotter and drier due to climate change, our sustainability will depend upon technological advances in food production and water sourcing and recycling. Technology will also need to be applied to reconstructing habitats. Our sustainability will ultimately depend upon whether or not we can secure the nation’s biodiversity.

The other limitation to growth is cultural, not environmental. Australians are used to a certain quality of life and a big part of this is a sense of spaciousness in our residential areas. Generally speaking, communities see increased density as a threat to their sense of place and resist it. What makes population growth now so different from any other time in our history is that for the first time our cities are evidently struggling to cope. In Sydney, services are collapsing and the only available land for further development is the city’s remnant food bowl, unless anyone is prepared to countenance developing its national parks.

Brisbane’s laid-back lifestyle is a fading memory as it morphs into a two-hundred-kilometre blur from the Gold Coast to the Sunshine Coast. Melbourne’s urban growth boundary has snapped and the flood gates for massive new tracts of suburbia have opened, while Perth is already the most sprawled city on earth but likely to reproduce itself once over in the next forty-five years. What form of transport will hold it all together?

Whereas in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century rampant urban growth was a sure sign of progress, the progressive city of the twenty-first century will be one that can adapt effectively to environmental limitations and infrastructural overload. But cities are cumbersome, deeply entrenched structures and urban planning is often a blunt, bureaucratic instrument of change. The challenges of twenty-first-century urbanism require new means of inspiring and effecting change. Above all, they require creativity from both the political class and the professions connected to urban design.

Planners, architects and landscape architects must show the community how new forms of development and increased density can make a better city, not just a more crowded city. And where there are sensible opportunities for increased suburban expansion, then it is incumbent upon planners, architects and landscape architects to create innovative suburbs. Suburbia can remain a viable form of urbanism if its components are creatively adapted to twenty-first-century challenges. Business as usual is untenable.

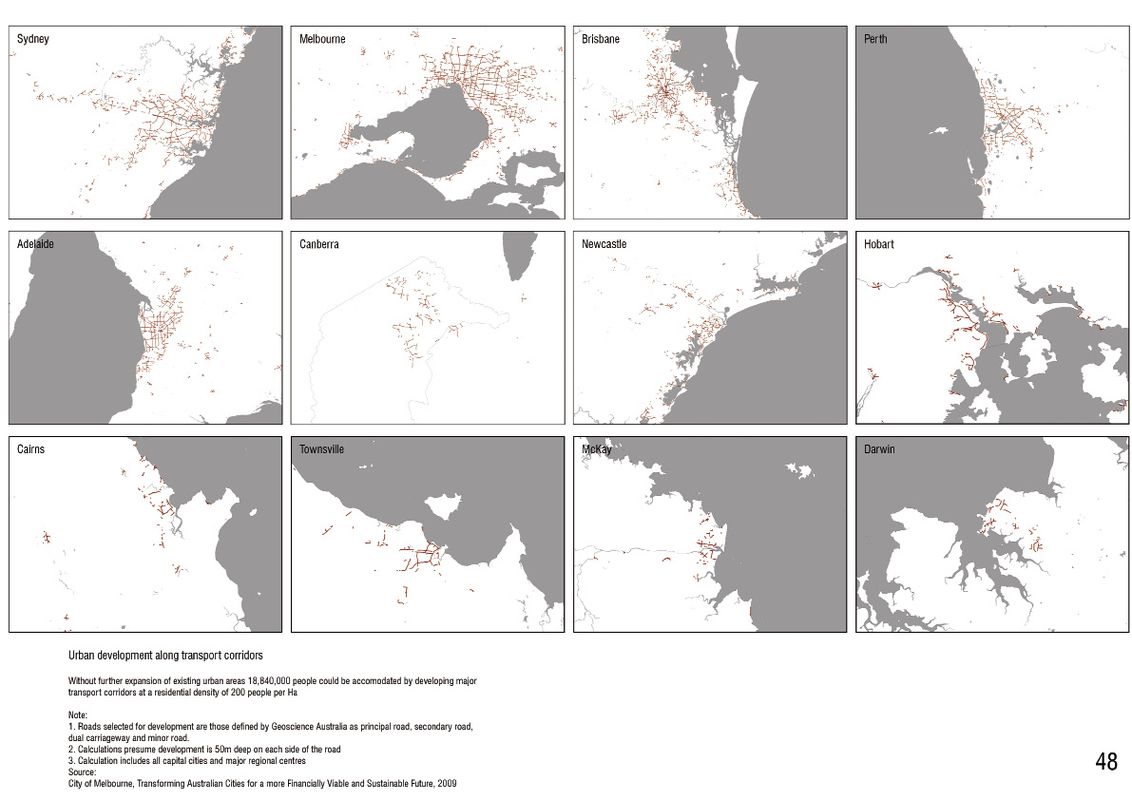

Australian cities have good opportunities for densification. For example, in our book Boomtown 2050: Scenarios for a Rapidly Growing City we showed how Perth could easily double its population in a beneficial manner. Similarly, Professors Rob Adams and Kim Dovey in Melbourne have proven that most of Melbourne’s future growth could be absorbed by infill development along that city’s main arterial roads. When we apply this infill concept to all the nation’s capital cities and major regional centres, we calculate that eighteen million people could be accommodated (Figure 2). In other words, Australian cities do not need to sprawl any further, providing of course that Australians will accept living in apartments along major transport corridors.

Increasing density along transport corridors seems like a sensible idea but these environments are hardly desirable places to live. If we’ve learnt one thing from the twentieth century it is that we should add density, particularly in the case of low-cost housing, where we have good amenity. Good amenity means more than just proximity to public transport. The unique amenity of each Australian city should be identified and then creative solutions developed as to how more people can live close to that amenity. It is hard, however, to imagine that all of Australia’s existing capital cities and regional centres can absorb an extra twenty to thirty million people.

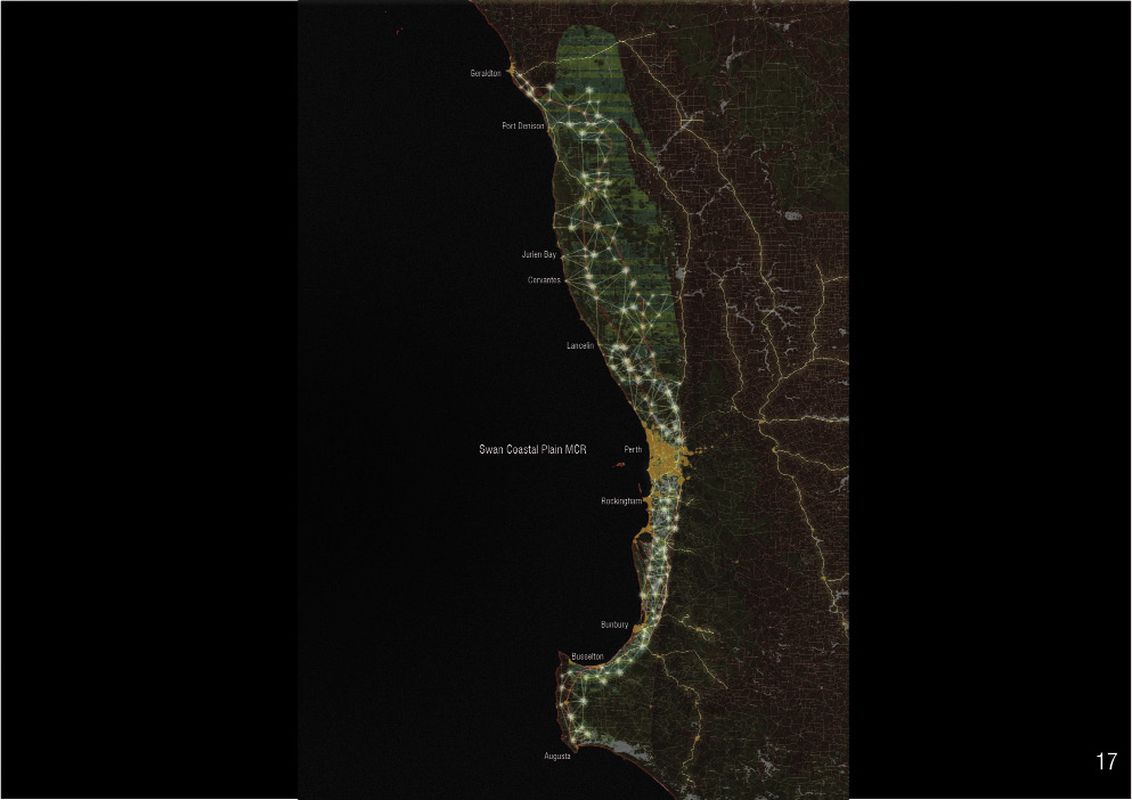

Certainly no politician in their right mind is going to say they should. So what to do? Along with partially increasing the density of our existing urban areas, we should also look for opportune places for entirely new settlements (Figure 3). Landscape architecture can play a major role in this. For starters, a new city, or cities, in the north-west of Australia is a compelling idea. So too is a mosaic of new towns on already cleared land throughout the six-hundred-kilometre-long Swan Coastal Plain north and south of Perth (Figure 3, Figure 4).

Similarly, there is surely scope for new settlements along a rapid transportation corridor linking Brisbane, Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne and even across to Tasmania. An ageing population might migrate north to a new belt of development between Cairns and Mackay. Could Alice Springs sustain a larger population?

And we don’t mean just bulldozing our way forward – those days are over. We mean well-designed urbanism based on innovative technologies that are adapted to our fragile landscape and the environmental limits of the twenty-first century. New and existing cities need to be re-imagined as metabolic, not mechanistic. In this regard Australia’s predicted growth is, more than anything, a creative design challenge. If landscape architects don’t apprehend this moment in time, then others less qualified to do so will.

Source

Practice

Published online: 16 Apr 2016

Words:

Richard Weller,

Julian Bolleter

Images:

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2010