Terms such as “disaster preparedness” and “disaster mitigation” have become mainstream as we head deeper into the Anthropocene. The global environmental crisis is at the forefront of our collective experience, more so now than it has ever been. The science is telling us that climate-related disasters such as drought, wildfires, cyclones and floods will continue to increase over the next century. Among those most susceptible to such events are the world’s poor and displaced people, living in refugee camps and informal settlements in developing countries.

In 2014 the Australian Government cut $7.6 billion from its foreign aid budget over five years.1 But worldwide, the need for humanitarian assistance continues to grow, urban density continues to increase and disaster scenarios are compounding. Informal settlements and refugee camps are becoming more commonplace and more populated. As much of humanity seeks refuge from civil unrest, climate disasters and economic downturns, now is the time to promote the role of the landscape architect in the delivery of aid and design to the communities most in need.

Laurie Lee, chief executive of Care International UK, recently asked in an article in The Guardian, “How do we make life better for people living as refugees for generations?”2

This is one of the critical questions of the Anthropocene. Mass human migration and rapid urban population growth across developing countries are transforming informal settlements and refugee camps from a temporary to a more permanent community typology. Refugee camps can be required for decades – for example, Dadaab refugee complex in Kenya is twenty-five years old and houses some 330,000 people.3 At what point does a camp transcend its original purpose to become something else? Landscape architectural practice, with its foundational understanding of ecological, social and economical systems, is perfectly placed to successfully collaborate with development aid agencies through this extraordinary shift in human settlement scenarios.

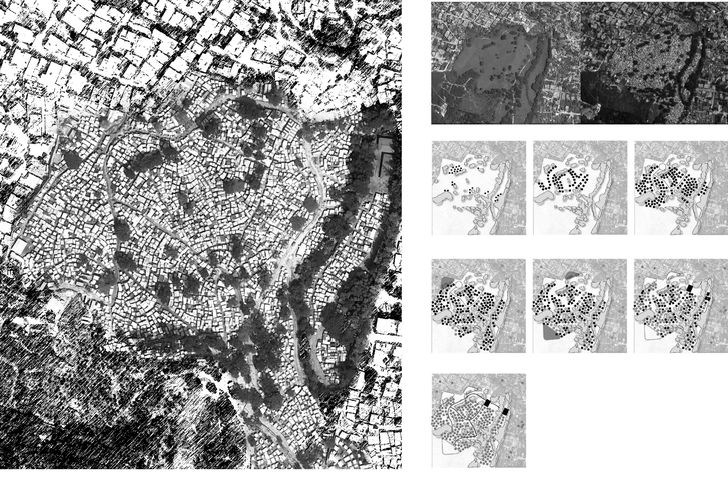

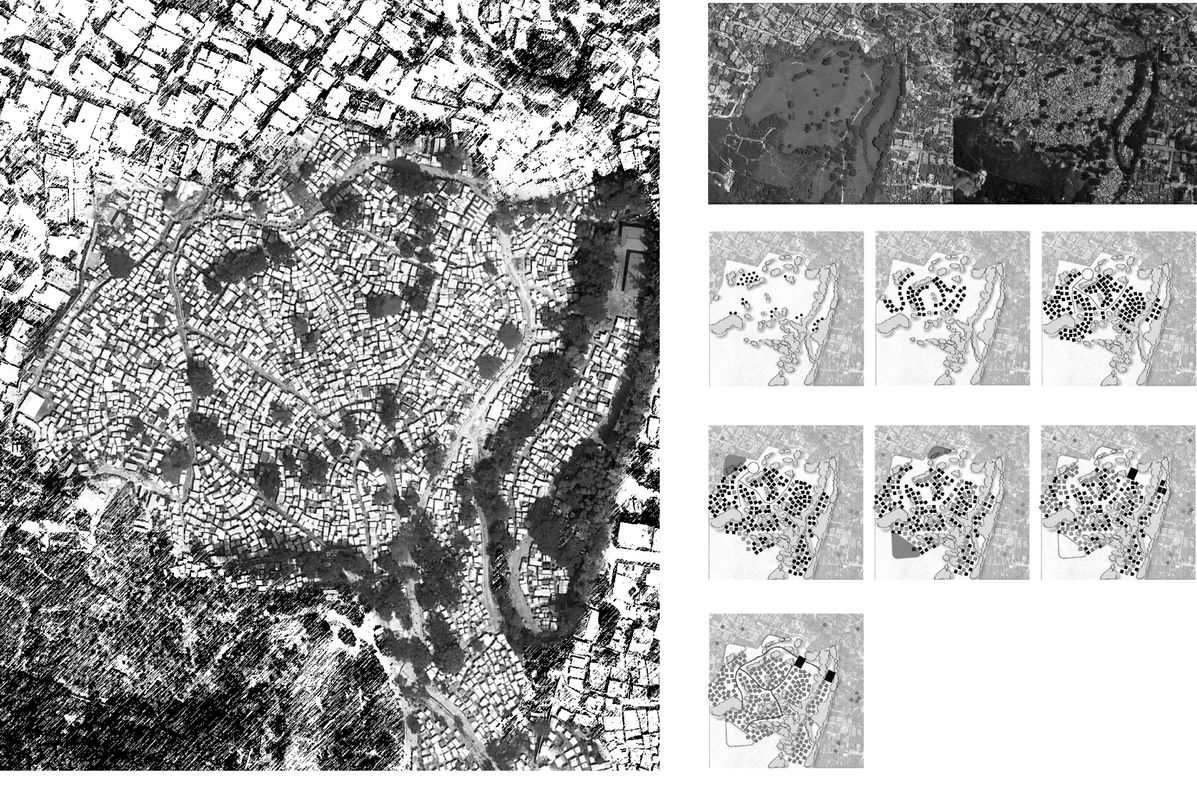

Mapping the growth of the Pétionville Club golf course refugee camp in Port-au-Prince, Haiti following the earthquake that occurred on 12 January 2010.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory puts the physiological needs of the human as the primary priority for survival. This is a fundamental and driving theory for aid agencies, helping them to prioritize and successfully deliver aid. Landscape architecture, with the correct methodology, has the potential to meet those physiological needs. Air, food, water and shelter are all products of landscape systems, as are opportunities for children to learn, play, live and feel free. All kinds of ingenious architectural and industrial design solutions have become vital components of the overall emergency response aid toolkit. But as landscape systems fundamentally underpin people’s basic needs, landscape architecture is a good place to begin in terms of disaster relief.

How informal settlements and refugee camps can be designed to address a complex range of ongoing needs and how best to implement development infrastructure post disaster are issues that require immediate attention. Landscape architects are perfectly poised to contribute to these complex scenarios. Elaborate situational issues and problems with nonlinear or untidy systems are intrinsic to the discipline. Despite this, the profession often seems fixed in a holding pattern. Landscape architecture has the capacity to aim higher and act globally by expanding the practice into unfamiliar territories in new, self-defined roles. Major events in the past decade, such as the earthquakes in Nepal and Japan, flooding in cities such as Jakarta and the refugee crises in Europe, make it clear that our urban environments need to be rethought – equally radically and pragmatically – in terms of their capacity to accommodate the fluctuating and immediate needs of people seeking refuge. The dream of a singular panacea for our anthropogenic crisis has evaporated like a mirage. Urban typologies such as parks, squares and streets must be reconsidered in terms of their agency in unfolding crises. How can these spaces quickly transform to support the ever-shifting, complex and ongoing needs of communities through each stage of the disaster cycle?

Acceptance of informal settlements in our urban environment is the first step toward reconsidering the way that we design our cities. Through understanding the unique nature and spatial operations of such communities, and recognizing their place within a greater system, the landscape architect has the ability to create a design methodology that operates across different social and infrastructural scales. There is no singular outcome: the opportunities derive from existing conditions, use and spatial hierarchies of the site. When we allow ourselves as designers to build upon these existing site relationships, new and interesting urban typologies are able to form.

Informal settlements are complex environments. They exist in a continual state of flux and as such the design approach needs to be agile, transparent and accepted by the community. Any site can have a number of overlapping ownerships and stakeholders (such as families and religious and formal community leaders) and existing programs that need to be considered, along with environmental pressures such as flooding and erosion. Potential site users also need to be identified, in a way that goes beyond the above-mentioned stakeholders. They may also be children, women, informal business owners and the elderly. Each user has a specific existing relationship with the site and ideally the broadest possible scope of these relationships would be recognized and enhanced through any design intervention. Design outcomes should be multilayered in their programming, enhancing economic, social and educational opportunities while also mediating ecological degradation and environmental pressures. They must maximize the benefit of aid funding to improve the public realm of these communities in an immediate and fundamental way.

In response to increasing numbers of impoverished children and communities living at risk in cities of the developing world, aid agencies have begun to focus on urban-based programming. Landscape architects have the knowledge and skills required to tackle this complex condition and are in a position to educate and collaborate with aid organizations to create lasting, sustainable outcomes. It is in these highly urbanized environments in the developing world that the potential for the built environment to transform living conditions for disadvantaged communities is at its greatest. In particular, landscape architects are trained to recognize opportunities for social congregation, play, education and green infrastructure. We can assist by fitting pragmatic measures such as sanitation engineering and water system design into existing aid program budgets. Most importantly, we can embed disaster preparedness into built outcomes to enrich and improve people’s lives.

1. Karen Barlow, “Budget 2014: Axe falls on foreign aid spending, nearly $8 billion in cuts over next five years,” ABC News, abc.net.au/news/2014-05-13/budget-2014-axe-falls-on-foreign-aid-spending/5450844 (accessed 6 June 2016).

2. Laurie Lee, “How do we make life better for people living as refugees for generations?” The Guardian, 5 May 2016.

3. Laurie Lee, “How do we make life better for people living as refugees for generations?”

Matthew Hamilton and Niki Schwabe are founders of Melbourne-based Emergent Studios Landscape Architecture (ESLA). Since 2012, the practice has been working on the Ciliwung Social Infrastructure Project with the Yayasan Interkultur Foundation in Jakarta, Indonesia to help deliver vital infrastructure to informal settlements. This work builds on Hamilton’s research into the role of the landscape architect in informal settlements, for which he won the 2011 Hassell Travelling Scholarship.

Source

Practice

Published online: 5 Dec 2016

Words:

Matthew Hamilton,

Niki Schwabe

Images:

Matthew Hamilton

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2016