Unspoken Spaces, Studio Olafur Eliasson, Thames and Hudson, 2016, hardcover, 416 pages.

I remember seeing an exhibition of Olafur Eliasson around the turn of this century in New York. Titled “Your now is my surroundings,” the exhibition saw Eliasson seemingly turn the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery (formerly Bonakdar Jancou Gallery) inside out – reorientating the relationships between visitor, architectural enclosure and external environment. In this show, all the main characteristics of Eliasson’s oeuvre were present. Clearly engaging with architecture, the piece worked to configure architecture primarily as an experience rather than an as a pure formal exercise of tectonics. Particularly foregrounded in this show was a lively combination of experiential and geometrical inquiry, undertaken to explore the relationships between spatial perception and bodily deportment through the creation of a kind of viewing machine – one that served to proliferate viewpoints and complicate subject–object relationships. If I read my notes correctly, the show was also extolled by the gallery as dealing with “issues of movement, social relations and individual freedom, or rather, the freedom from homogeneity of the heavily coded public space.” It was this engagement with public space that particularly took my interest, as I had, at the time, just completed one of my first public art projects in Melbourne.

In the intervening years, Eliasson has gone on to become one of the world’s major contemporary artists, and his practice continues to inspire me. So it was with great interest that I picked up his most recent monograph, Unspoken Spaces. It is an elegant book to hold and to read, containing a comprehensive overview of his practice. One of the book’s great achievements is that it gathers what is an extraordinary range of projects proliferating across most of the creative disciplines into a coherent whole. This is not to be understood as a closed, totalizing whole, but rather as a generative assemblage, or what Eliasson calls a “patchwork of territories” and a “polyphony of voices.” It is this openness and inclusiveness that is also at the heart of Eliasson’s practice. As he states in his introductory remarks, a defining feature of his firm and of the works made by it is a “spatial hospitality.” It is this hospitality, combined with a restless intellectual curiosity, that allows Eliasson to move with seeming ease between disciplines – and to avoid the category problems that still dog many of those working in the expanded field between disciplines, particularly between art and architecture.

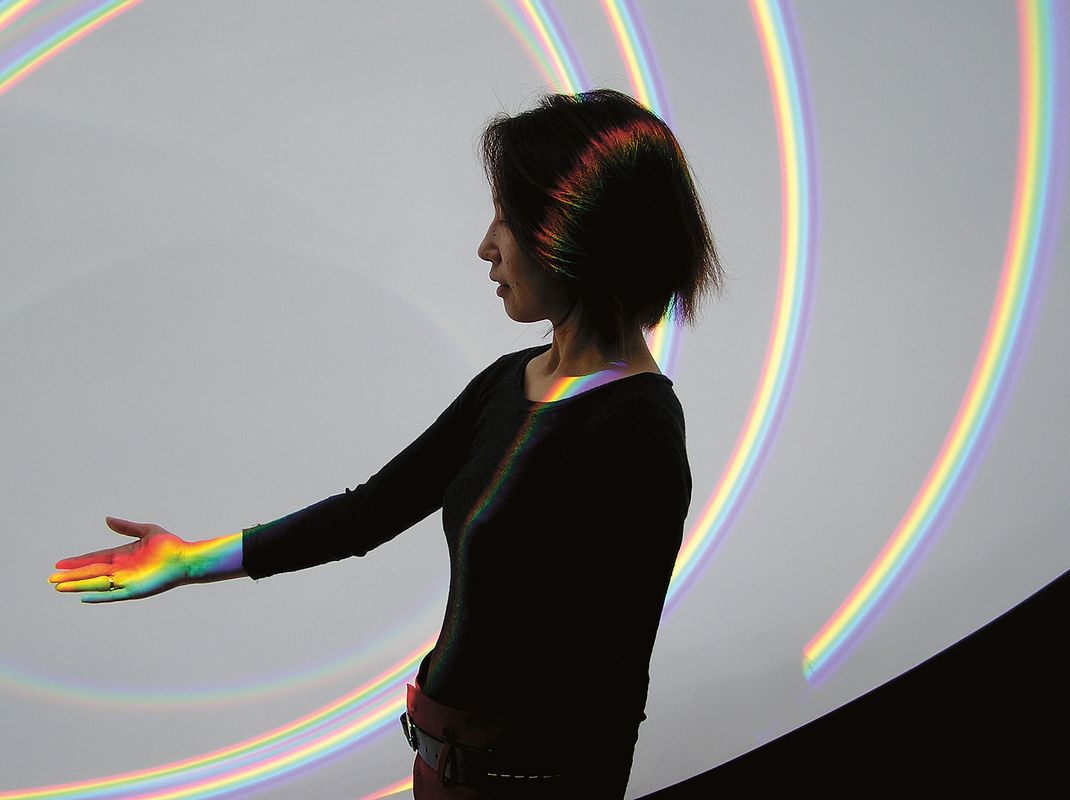

Sunspace for Shibukawa (2009) is a polished stainless steel observatory at the Hara Museum ARC in Tokyo, designed to chart the path of the sun as it (seemingly) moves across the sky. On sunny days, visitors perceive arcs of light projected onto a curved surface.

Image: Studio Olafur Eliasson

Interdisciplinarity and collaboration, as defining characteristics of Eliasson’s practice, are recurring themes of the book and ones that are particularly explored by Alex Coles in a chapter called “The Art-Architecture Ping-Pong,” a phrase that makes collaboration seem more a matter of competitive individualism than I think Eliasson intends. Further fine essays explore other major concerns of the practice, including an essay by Carol Diehl and Terry Perk focusing on mathematics/geometry, by Lorraine Daston on light, and by Eric Ellingson and Timothy Morton on memory and time respectively.

Across 416 engrossing pages the book amply demonstrates Eliasson’s skill at creating “models of space defined by movement.” What emerges with particular clarity is the interrelationship between atmosphere and built structure. I am not the only one to see the pavilion as a primary structural/spatial motif in his work. The pavilion has long been a favoured tool for architectural experimentation and spatial exploration and it serves exactly this purpose for Eliasson. Indeed, almost every piece of work by Eliasson can be seen as some kind of pavilion, meticulously designed to generate specific atmospheric and affective/sensory experiences. If architecture can be defined as that which makes present the play of light, then this is exactly what Eliasson explores over and over again with great beauty and at times, dare I say, spectacular success. This tendency for the visually spectacular is one reason that leads many to call his works “visionary,” but this is at the expense of a more nuanced and fully embodied sensorial experience. It is, paradoxically, contrary to the claims of “freedom from homogeneity” often made of the work.

In contemporary physics and cosmology it is argued that what we call atmospheres and affective relationships constitute 99 percent of the world, while all that we think of as concrete – the facticity of things – constitutes a mere 1 percent of the cosmos. It is of some paradox that in Eliasson’s work so much that is “solid” is needed in order to orchestrate the immaterial. Where he attempts the same, but with more minimal, less tectonic means, the work looks (in reproduction at least) less successful. Those projects that don’t default immediately to objects (pavilions), and which venture into what could be called the truly relational fields of landscape architectural practice, seem to lack his usual assurance. Those few explicitly landscape projects that elude identifiable formal expression in the vertical plane (i.e. non-object based), such as Proposal for a park (1997) or Non-stop Park (2009), are somewhat tentative or necessarily diagrammatic. The works that defy pictorial reproduction and which eschew spectacle are the very ones that come closest to genuine participatory interrelationships and performative freedom. But here we verge on a kind of participatory work that Eliasson approaches yet does not fully embrace. This would seem to identify a boundary of Eliasson’s art – let’s call it his performative and choreographic limit. To continue from here we would need to be talking about someone else – William Forsythe, Francis Alys or Tino Sehgal, perhaps?

Undeniably, Eliasson makes work of great beauty, intrigue, elegance, and aesthetic and intellectual richness. Despite my equivocations regarding the “spectacular” turn of some of the work, this is an excellent book for all those interested in Olafur Eliasson and the tradition of interdisciplinary practices and discourses that explore “how we construct the world, how this affects us and how else we might imagine it.” This re-imagining of our lived environment is surely an enterprise of ever-growing importance – one to which Eliasson proves to be more than a dedicated champion.

Order the book here via Book Depository.

Source

Review

Published online: 19 Jan 2017

Words:

Charles Anderson

Images:

Karl Rabe,

Studio Olafur Eliasson

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2016