Over the past decade, Australian landscape architecture has grown in its range and acuity of expression. These achievements are recognized around the world, but the opportunity to select ten works of significant Australian landscape architecture needn’t reaffirm this acknowledgement. Rather it is an opportunity to explore whether the profession is well-placed for the next ten years and where the profession is performing well and which areas require more thought and energy.

The jury (Catherin Bull, Janet Holmes à Court and Scott Hawken) has attempted to do this by selecting ten projects that help frame future directions and challenges. Five areas of engagement are outlined to situate and expand the cultural reach and ambitions of the selected projects. Perhaps it is too ambitious to expect ten projects to represent the breadth of issues and approaches necessary for the design of inclusive, resilient and biodiverse cities. Nevertheless each project demonstrates innovation and creative engagement in one or more of these five areas and gestures where landscape architecture can decisively contribute into the future.

1. Civic and inclusive urban space

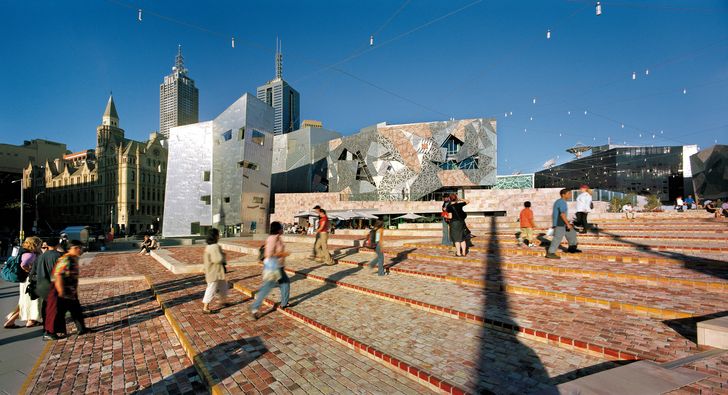

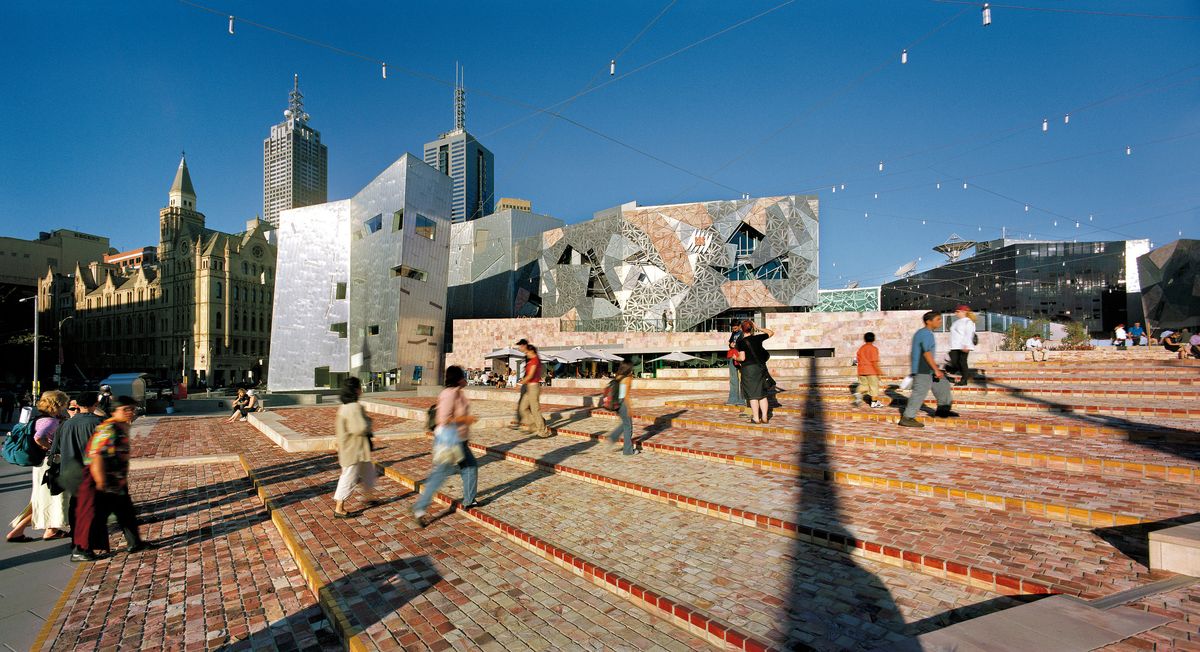

The public domain is a contested space and in today’s neoliberal world, something that must be relentlessly fought for. The two selected civic projects vigorously support lively human interactions and relate to the city spatially and intellectually in a way that magnifies their program and actual footprint. Federation Square in Melbourne is an immensely complex project that combines a nineteenth-century scale and content with a very contemporary expression. It is well-loved, popular and the site of genuine public life. The second selected project, North Terrace in Adelaide, was delivered in an equally contested process, which was navigated with dexterity by the landscape architects, Taylor Cullity Lethlean. The project involved the transformation of Adelaide’s ragged edge, and the public interface of a range of competing and very vocal institutions, into an invigorating and coherent boulevard. The boulevard has been crafted as a street to inhabit and manages to span the demands of civic coherence and local context with sensitivity and refinement. Both projects champion the continued importance of streets and squares in our cities and highlight the paucity of such spaces in Australian cities generally. The Cairns Foreshore Redevelopment was also well discussed by the jury who commends it for reimagining tropical informality as a civic space that’s welcoming for both visitors and locals alike.

Federation Square (landscape) by Karres+Brands with Lab Architecture Studio and Bates Smart for Office of Major Projects, Melbourne, Victoria, 2002.

Image: John Gollings

North Terrace Redevelopment by TCL with Peter Elliott Architecture and Urban Design, Paul Carter, James Hayter and Hossein Valamanesh for Adelaide City Council, 2011.

Image: John Gollings

2. Cultural identity

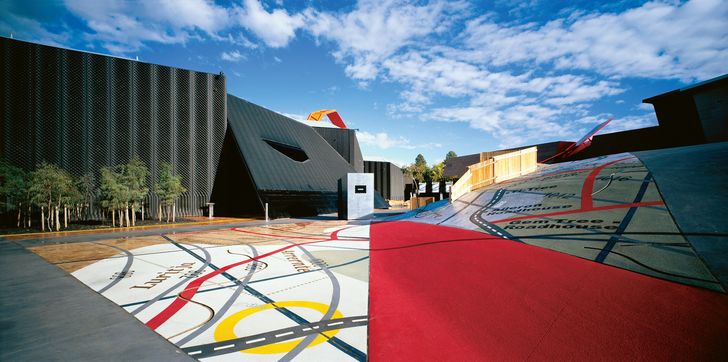

Cultural identity often goes unquestioned as a natural condition rather than an active creation. Two projects that have decisively moved forward conversations on identity politics, urge us to both reconsider and recreate national identity. Both “gardens” of “Australia,” The Australian Garden in Victoria and Garden of Australian Dreams in Canberra appear very different on the surface, but closer examination reveals a common engagement with multiple identities, unravelled metaphors, and a sincere engagement with Australia’s mental landscape. Both attempt to be popular and simplify complex realities and meanings. In contrast to the “official” conversations on cultural identity embedded in the above projects, the jury believed the category of community landscapes was something that needed greater championing by the profession, empowering urban operations and thoughts beyond professional boundaries. True community projects challenge the authorship of the landscape architect in favour of a collaborative process and a healthier society.

Australian Garden by TCL with Paul Thompson, Edwina Kearney, Mark Stoner, Greg Clarke and Mish Eisen for Royal Botanic Gardens, Cranbourne, 2005 (stage 1), 2012 (Stage 2).

Image: John Gollings

The Garden of Australian Dreams by Room 4.1.3 (Richard Weller and Vladimir Sitta), 2001. The garden is the centrepiece of the National Museum of Australia, designed by architects Ashton Raggatt McDougall and Robert Peck von Hartel Trethowan.

Image: Chris Elliott

3. Urban adaptation

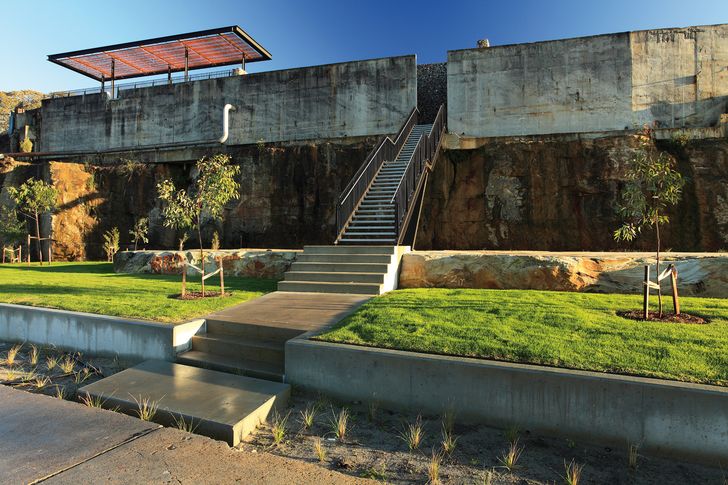

The repurposing of industrial elements with imagination and creativity is of high priority in resource-scarce times. How to combine obsolete parts of the urban landscape with ecological and social concerns and narratives is a continuing and complex experiment. In recent years a range of projects have convincingly updated landscape architecture’s methods of remaking post-industrial landscapes. These works not only remediate badly damaged sites, but have also introduced a new sophistication to the urban park typology with surprising spatial manipulations and a dexterous handling of existing materials. The two selected projects, Ballast Point Park and Paddington Reservoir, both in New South Wales, confidently achieve this, addressing an array of historical conditions while grappling with future challenges, both global and local. Such energized approaches are necessary in the re-making of cities as authentic yet dynamic places.

Ballast Point Park by McGregor Coxall with CHROFI for Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority, Sydney, New South Wales, 2009.

Image: Christian Borchert

Paddington Reservoir by JMD Design and Tonkin Zulaikha Greer for City of Sydney, 2009.

Image: Brett Boardman

4. Urban biodiversity

Landscape architects, more than any other broad-based design professionals, engage with living components of our cities and their interrelationships. They often do this in compromised situations when biodiversity is on the back foot and in retreat. While managing this retreat and shaping new, more resilient ecologies may seem impossible at times, these are challenges that the two selected projects have embraced. They exemplify, in the language of ecology, the corridor (Eastlink in Melbourne) and the patch (the National Arboretum in Canberra). Eastlink integrates massive road infrastructure into a culturally and ecologically sensitive landscape to create a compelling work of landscape urbanism. The robust arrangement of ecosystems and community facilities in relation to such major infrastructure is a rare achievement. The new networks of pedestrian paths and cycleways and of reconstructed wetlands, streams and vegetation, connect ecosystems and suburbs and establish a new benchmark in ecosystem reconstruction. In contrast, the National Arboretum raises awareness through a startling stand-alone urban biodiversity project on an extraordinary spatial and temporal scale. Other note worthy projects include the recently completed Sydney Park wetlands, a flagship project for integrating and recycling urban stormwater with sophisticated constructed ecological systems in a park setting.

The metropolitan park system as a significant type of landscape architecture has not been well addressed within most Australian cities over the past ten years. This requires a much more vigorous design commitment as Australia continues to urbanize.

The National Arboretum by TCL with Tonkin Zulaikha Greer for Shaping Our Territory Implementation Group, ACT Government, 2013.

Image: John Gollings

Eastlink by Tract Consultants and Wood Marsh for Connecteast, Melbourne, Victoria, 2008.

Image: Courtesy of ConnectEast and Heaven Pictures

5. Density and green infrastructure

A central challenge for the next decade is for Australian cities to increase density whilst improving environmental qualities and social wellbeing. Finding innovative ways to integrate green infrastructure into urban fabric in the Australian context is necessary to achieve this. The risks and the rewards associated with integrating such infrastructure require careful consideration and cooperation between disciplines and the commitment of strong clients. Over the past two decades, Victoria Park in Zetland, Sydney, emerged as the most innovative example of integrated high-density living and water-sensitive urban design, opening up opportunities for other similar works. The result of a collaboration between the NSW Government Architect’s Office, Hassell and water engineers and scientists Tony Wong and Peter Breen, the park’s design has turned the problematic flooding conditions of the site into a dynamic and safe public landscape that celebrates water. The quality of the public domain design is evident in the way radical engineering solutions have resulted in an urbane, everyday civic vocabulary.

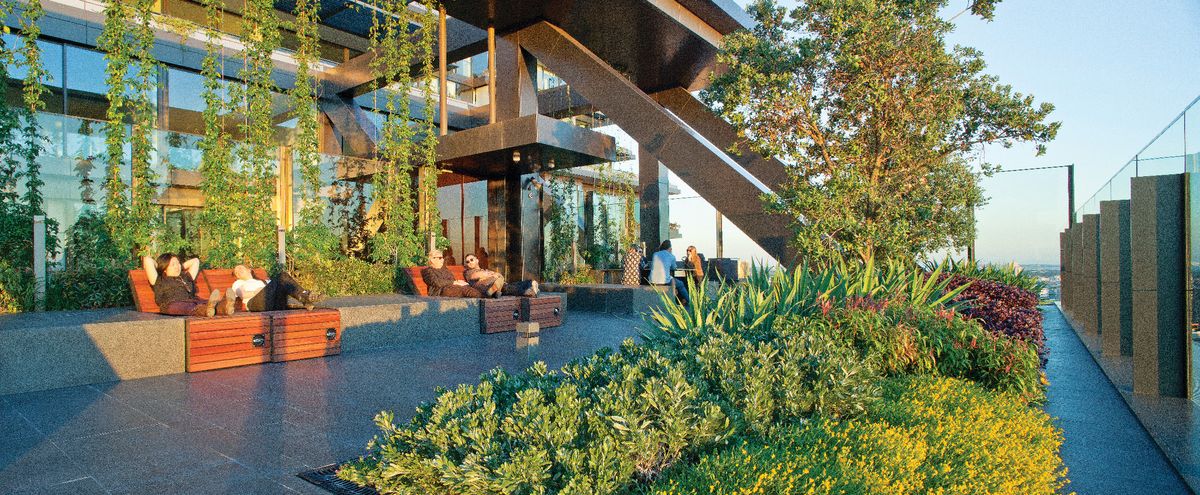

Nearby, One Central Park is another radical project that integrates biological components into the facades and roof terraces of the building in a convincing aesthetic. Inspired by the sandstone ledges and caves of Sydney, the building facade becomes the site for a landscape experience. The new technologies integrated with the two projects were untested on such a scale in Australia at the time of their implementation. Both developments are testbeds for new biophilic urban forms that require new thinking about energy, technology, climate and maintenance to make them sustainable in the long term.

Victoria Park Public Domain by Hassell with NSW Government Architects Office and Turpin + Crawford Studio for Landcom, Sydney, New South Wales, 2002.

Image: Max Creasy

One Central Park by Ateliers Jean Nouvel, PTW Architects, Patrick Blanc (green walls), Aspect|Oculus (design development, documentation and site advice) and Turf Design Studio (concept design) for Frasers Property Australia and Sekisui House Australia, Sydney, New South Wales, 2013.

Image: Simon Wood

—-

Scott Hawken is a researcher and lecturer at the University of New South Wales and co-convenor of the Smart Cities Research Cluster. In his work he uses high-end geospatial technology and satellite data to better understand rapidly emerging urban environments.

Catherin Bull is emeritus professor of landscape architecture at the University of Melbourne, adjunct professor at Queensland University of Technology, chair of South Bank Corporation, and a member of the Building Queensland board and of the design directorate of UrbanGrowth NSW. She is also a contributing editor to Landscape Australia.

Janet Holmes à Court is owner of the Janet Holmes à Court Collection. She is a chairperson and board member of numerous arts and cultural foundations, organizations and institutions, including the Australian Urban Design Research Centre, the Australian Institute of Architects Foundation and the New York Philharmonic International Advisory Board, among many others.

Source

Review

Published online: 1 Mar 2017

Words:

Scott Hawken

Images:

Brett Boardman,

Chris Elliott,

Christian Borchert,

Courtesy of ConnectEast and Heaven Pictures,

John Gollings,

Max Creasy,

Simon Wood

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2016