The low, wooded mountain ranges surrounding the Chinese city of Nanjing are rich in geological deposits from the earth’s Palaeozoic era and subsequently have a history of significant archaeological findings. This includes the 1993 discovery of Homo erectus nankinensis fossils (a subspecies of Homo erectus) dubbed Nanjing Man. Taking heed of the site’s fascinating geological formations, the sweeping, layered design of the Nanjing Tangshan Geopark Museum appears as an extension of the existing topography’s contours. The geology and anthropology museum, designed by French architecture practice Studio Odile Decq, has been built into the face of an ancient quarry and the public domain, designed by Hassell, seamlessly extends into the surrounding parkland.

Attesting the area’s historical importance, Hassell’s scheme honours the site’s connection to the Palaeozoic era with “prehistoric” feature gardens. The Palaeozoic era was a major interval of geological time that began about 540 million years ago with the Cambrian explosion, which saw huge diversification of life on earth and ended with the Permian extinction. Six gardens have been conceived to represent the major divisions of the Palaeozoic era: Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian.

These periods provided a taxonomy from which the designers could draw inspiration, dictating plant and stone selection. Angus Bruce, principal and head of landscape architecture at Hassell, spoke with Landscape Australia’s Ricky Ray Ricardo and Hannah Wolter about how the designers simulated environments from hundreds of millions of years ago to create didactic experiences that are engaging and immersive.

The overall look of the plaza echoes the site’s contour lines, which shift like geological activity.

Image: Johnson Lin

Landscape Australia: Could you tell us about the importance of the site’s history as a quarry?

Angus Bruce: That’s how the site became archaeologically important. During quarrying activities and the discovery of the cave [on site], ancient remains and relics were discovered. The building’s been nestled into part of that quarry face, and that became part of the natural language for the whole design. Landscape didn’t lead architecture, and maybe it’s fair to say [the architecture] didn’t complete the landscape response – they were quite heavily stitched together and the outcome reflects that now.

What are the various stages of this project?

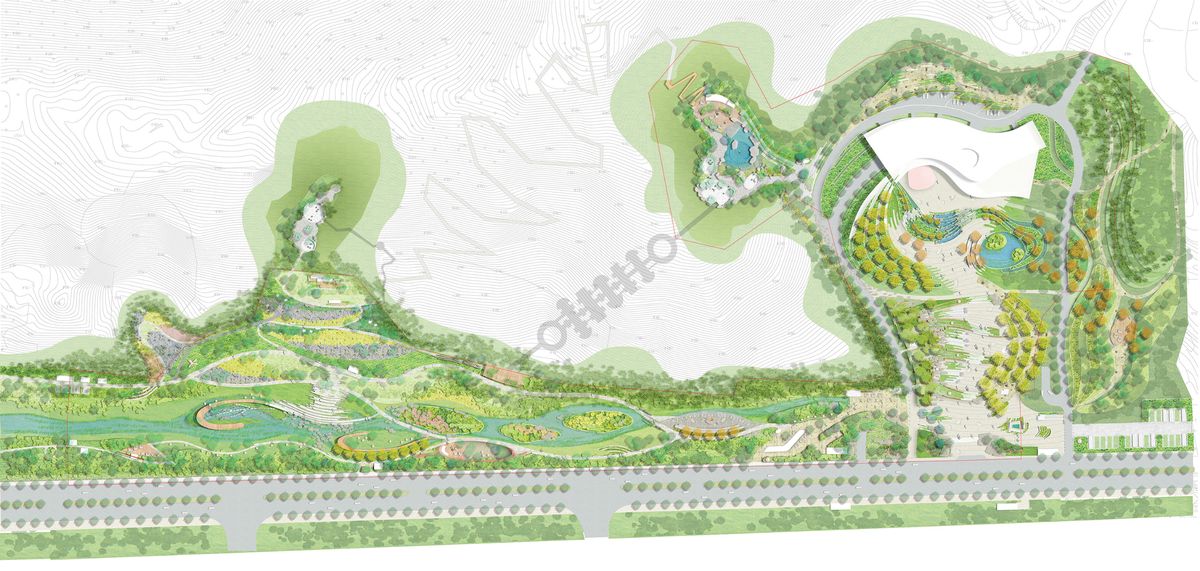

Everything you see is part of a larger masterplan, which is part of our successful entry [in the 2013 international design competition for the museum’s gateway plaza and surrounding parkland]. Thus far they’ve developed stage one – the museum building and the primary arrival precinct, as well as part of the learning and history component at the forecourt. Stage two is the entry plaza connecting the museum to the road edge, which is where bus coaches and a future metro station will be built, and then stage three is an extended riparian and wetland corridor, a restorative corridor/park that forms part of the education experience.

Nanjing Tangshan Geopark Museum site masterplan.

Image: Courtesy Hassell

Could you take us through a typical journey from the bus terminal to the museum entrance?

The design references the six periods of the Palaeozoic era with six gardens, which form an important part of this meandering route through the public domain to the building’s entrance. We’ve only got two of those six gardens in place at the moment; the other four are still pending.

Each of the six “garden rooms” will allow for an experience within each of the Palaeozoic’s six periods, so that we do not have to layer the entire plaza with the correct remnant stone and so forth; they end up being little microcosms of the period in a more forceful context. So your path from the drop-off point to the museum itself will encompass a couple of optional journeys through the plaza, offering an immersive experience that exposes you to the key geological, botanical and climatic characteristics of each period.

I’m interested in this idea of the gardens representing the different periods within the Palaeozoic era. Are they experienced chronologically?

Yes, but the layout also allows you to cut and traverse through the geology so you can really understand the layering of how deep you are within [a particular] period, and you can also understand where you are in the context of plant life, because when you start in the Cambrian period and you move through to the Permian period, you’ve got no vegetation through to lush vegetation. So this was part of the juggle, knowing we would need to represent a period that was purely volcanic rock: how do we make that aesthetically comfortable?

Children play on boulders that reference the Cambrian period of the Palaeozoic era.

Image: Johnson Lin

What level of annotation is present? Do you have plans for a virtual layer of user experience?

The aim is that the direct learning is done within the museum, but that the plaza prompts curiosity. We don’t want everyone to finish their experience before they get to the front door.

Part of this is [achieved through the use of] signage and graphics. Due to the fact that you can’t get the same plant material that grew in Nanjing millions of years ago to grow in today’s climate, fernery for example, we’ve set up a graphic base and the plant material is represented through glass … it’s near impossible to [use] the exact plants and exact rocks of those periods. But we got close, and the rest of it’s done through visual aids, and then online or with tactile reading in two languages, English and Mandarin.

Have you experimented with microclimates to facilitate plant growth?

Yes, we have. With microclimates, we’ve sourced irrigation to saturate ground soil environments, or used misting to try to achieve them. It’s the heat that is the hardest part, trying to get the right temperature in winter and summer, which is why some of the gardens will have to be these glass artwork representations of the historic tree ferns, which we simply can’t grow. The backdrop is intended to set the context, but the plant material itself won’t always be literal.

The geopark’s design integrates the fluid architectural form of the museum with the various attractions spread across the fifteen-hectare site.

Image: Johnson Lin

The landscape appears to be so well integrated with the building. Could you tell us about the collaboration with the architect?

It wasn’t really collaborative, not in the way we would use the term in an Australian context, or even a European or US context – the client sat between us. There was a bit of passing things back and forth, between the architect’s outcome and our outcome, but the client was very much in the middle. These were two separate parallel strengths, so we were constantly being informed by the work, but you didn’t have the ongoing direct dialogue that you would traditionally be used to. And the architects were also based in Europe, and we were on the ground in China.

What’s your experience of working in China and how does your practice manage these types of international projects? How do the scale and duration of a project like this differ from projects in Australia?

Well, we’ve been fortunate – Hassell has had a permanent team on the ground in China for about thirteen years. The projects that we’re now seeing pop up in awards are the fruits of years and years of invested time in China. I’m in China one week out of every six weeks, and I’ve done that for four years now. It’s exhausting. But there’s that much work and it really is quality work. We are not just competing against other Australian and Chinese practices, there are also very strong American-based firms bidding for the same projects.

On the scale and duration of development – from a competition concept in 2013 to a built outcome in two and a half years, that’s the pace of the Geopark project. You just couldn’t fathom something like this happening in Australia.

What is your sense of the current mood in China regarding development? Are things still moving fast or has there been a slowdown of late?

I would say it’s a build-up, if anything. There’s been increased focus here on public realm, urban design, fine-grain projects – reshaping and owning the city. That’s what we are seeing, anyway. All of the hero architecture, the iconic “identity buildings” that Chinese cities are known for, seems to have slowed, but not the overall speed, particularly with regard to developing spaces and places.

There’s far more demand to elevate the value and integrity of development, which ends up being underpinned by better environmental and social outcomes. It’s an intelligent shift, and definitely advantaging the landscape architects and urban designers working here.

Products and materials

- Plant List

- EVERGREEN TREES: Cedrus deodara (deodar cedar), Cinnamomum camphora (camphor laurel), Magnolia grandiflora (southern magnolia), Citrus medica (citron), Osmanthus fragrans (sweet osmanthus), Photinia x fraseri (red tip photinia), Photinia serrulata (Chinese photinia), Elaeocarpus decipiens (Japanese blueberry tree), Camellia japonica (Japanese camellia), Myrica rubra (yangmei). DECIDUOUS TREES: Celtis sinensis (Chinese celtis), Ginkgo biloba (Maidenhair tree), Koelreuteria bipinnata, Zelkova schneideriana, Liriodendron chinense (Chinese tulip tree), Prunus x yedoensis (Yoshino cherry), Sophora japonica (Japanese pagoda tree), Pistacia chinensis (Chinese pistachio), Pterocarya stenoptera (Chinese wingnut), Taxodium mucronatum (montezuma bald cypress), Prunus persica (peach tree), Viburnum macrocephalum (Chinese snowball viburnum), Lagerstroemia indica (crepe myrtle), Acer palmatum (Japanese maple), Acer palmatum cv. Atropurpureum, Firmiana simplex W. F. Wight (Chinese parasol tree), Metasequoia glyptostroboides (dawn redwood), Sapindus mukorossi (Chinese soapberry), Cercis chinensis (Chinese redbud). BAMBOO: Phyllostachys bambusoides (giant timber bamboo), Phyllostachys aureosulcata f. spectabilis (spectabilis), Phyllostachys heterocycla. GROUNDCOVER AND HERBACEOUS: Fatsia japonica (paperplant), Fatshedera lizei (tree ivy), Ligustrum japonicum ‘Howardii’, Lonicera nitida Maigrun (may green), Nandina domestica, Sabina procumbers (Endl.) Iwata et Kusaka, Pittosporum tobira (Japanese pittosporum), Rhododendron pulchrum ‘Sweet’, Gardenia jasminoides (cape jasmine), Buxus sinica (Korean littleleaf boxwood), Rosemarinus officinalis (rosemary), Gaura lindheimeri (pink gaura), Verbena bonariensis (purpletop), Farfugium japonicum (leopard plant), Tulbaghia violacea (pink agapanthus), Glechoma hederacea (ground-ivy), Euonymus fortunei, Nepeta cataria (catnip), Coreopsis basalis (golden-mane coreopsis), Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower), Forsythia viridissima, Iris tectorum, Hosta plantaginea, Oxalis articulata subsp ‘Rubra’, Zephyranthes candida (Peruvian swamp lily), Trifolium repens (white clover). GRASSES: Pennisetum alopecuroides (swamp foxtail), Arundo donax L. var. versicolor, Miscanthus sinensis ‘Variegatus’, Pennisetum orientale (oriental fountain grass), Acorus gramineus ‘Ogon’, Cortaderia selloana ‘Pumila’, Miscanthus sinensis (Chinese silver grass), Pennisetum alopecuroides ‘Little Bunny’, Liriope muscari cv. Variegata, Liriope spicata (monkey grass), Reineckea carnea, Ophiopogon japonicus (dwarf lilyturf), Cynodon dactylon (couch grass). AQUATIC PLANTS: Canna glauca, Hydrocotyle chinensis, Buddleja davidii ‘Royal Red’, Nelumbo nucifera (sacred lotus), Nuphar sinensis, Nymphaea tetragona (hardy waterlily), Thalia dealbata (powdery thalia), Typha orientalis Presl (bullrush), Myriophyllum verticillatum (whorl-leaf watermilfoil), Iris pseudacorus, Iris sanguinea, Lythrum salicaria Linn (purple loosestrife). ROOF GARDEN: Sedum lineare Thunb. T, Sedum spurium ‘Coccineum’ (dragon’s blood), Rosemarinus officinalis (rosemary), Imperata cylindrical ‘Rubra’, .Cynodon dactylon (couch grass)

Credits

- Project

- Nanjing Tangshan Geopark Museum Public Realm

- Practice

- Hassell

Australia

- Project Team

- Andrew Wilkinson, Walter Ryu, Yulun Liao, Eric Lee, Liangliang Wang, Shuping Ye, Angus Bruce, Jon Hazelwood, Sharon Wright, Chris Chesters, Sean Lin, Joiry Guan, Rohan Buckley

- Consultants

-

Architect

Studio Odile Decq

Local design institute Shanghai Julong Green Land Development

- Site Details

-

Site type

Rural

- Project Details

-

Status

Under Construction

Design, documentation 3 months

Construction 6 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Museums, Outdoor / gardens, Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Nanjing Tangshan Construction Investment and Development Company

Source

Review

Published online: 18 Apr 2017

Words:

Ricky Ray Ricardo,

Hannah Wolter

Images:

Courtesy Hassell,

Johnson Lin

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2017