Contemporary existence is a theatre of emotions. Being happy is a constant expectation, and there are books and courses readily available to help people achieve happiness. Anger, joy and fear are served up for our entertainment in reality TV shows based around home improvement, extreme sports and crime. Love is something to compete for against other “bachelorettes” and human relationships are played out on television and social media.

Emotional distance – the stuff of relationship breakdowns – sees a separation between ourselves and our cities. While all the cacophony of emotion-as-entertainment plays out around us and people strive to be happy at any cost, an authentic connection with our cities unravels. Loss of experience, a muting of the sensorial and a narrowing of the emotional spectrum are the collateral damage of the prevailing predilection for happiness and a seduction by the virtual world.

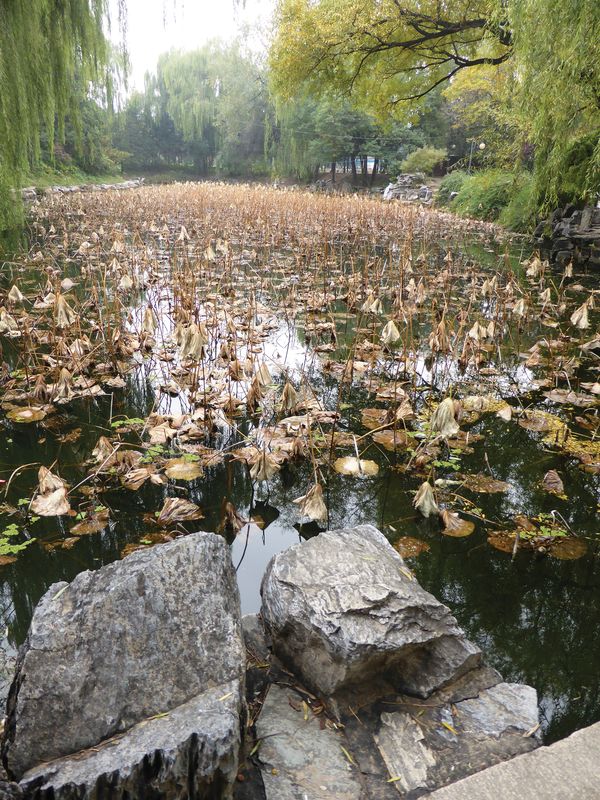

Moving places: travelling on a train through Portbou, Spain.

Image: Jacky Bowring

Life in the roiling maelstrom

But as geographer Nigel Thrift points out, “Cities may be seen as roiling maelstroms of affect. Particular affects such as anger, fear, happiness and joy are continually on the boil, rising here, subsiding there, and these affects continually manifest themselves in events which can take place either at a grand scale or simply as a part of continuing everyday life.”1 This embeddedness of emotion within the fabric of the city grounds it, authenticates it and elevates it above the fleeting melodramas of the virtual world.

Thrift also reminds us of the emotional range that makes up life in the city. Rather than a single-minded pursuit of happiness, wellbeing needs emotional balance. The ancient idea of the “humours” expressed equilibrium in a four-part system that balanced the phlegmatic (cool and introverted) with the choleric (dynamic and extroverted), and the melancholic (thoughtful and introspective) with the sanguine (humorous and outgoing). Humoural diagnosis was based on negotiating a balance, a sharp contrast to the current concern with happiness.

Cruel optimism and the happy filter

As we mine our urban lives for happiness, paradoxically we find unhappiness. Lauren Berlant describes this as “cruel optimism,” where “something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing” – for example, the wish to be like a televisual model family, to take the sorts of holidays you see your “friends” on social networking sites having, to get fit, to get thin.

The same thing happens in design, suggesting that caution is needed in terms of the kinds of utopias that landscape architects inevitably show in visualizations. Proposed urban parks, squares and residential developments are represented as places full of happy people – a child holding a balloon, a dog chasing a ball. The sky is blue and the sun is shining. No-one is sad; no-one is alone. When Jacob van Rijs of MVRDV visited Christchurch, New Zealand last year he talked about the idea of a “happy filter” that could be put over images, so that any grimy and desolate site could be bathed in a golden glow. Van Rijs was emphasizing the power of renderings to produce positive effects – perhaps a kind of Photoshop Prozac. As Berlant asks, “What happens when these fantasies start to fray – depression, dissociation, pragmatism, cynicism, optimism, activism, or an incoherent mash?”2

Ethics and the city

Contemporary culture veils and mutes experiences, reducing our urban emotional repertoire and starving us of a meaningful and authentic engagement with place. While it might seem unethical to suggest we should willingly impose places of sadness or fear on urban dwellers, it is also immoral to peddle promises of pleasure. Examples like the High Line linear park in New York are intriguing from an emotional perspective. As required by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, the graffiti was painted over, a sanitization of the patina of place. What is landscape architecture’s role in the public realm? To ensure that everything is sterilized, new and clean, and erase the traces of the past? What of those things that actually should make us sad? While some designers argue that sites of trauma should become therapeutic so people feel “better” after visiting them, isn’t it more fitting that we should feel sad, distressed, concerned, melancholy?

Complicit in the covering over of the wounded, sad and broken parts of the city is the concept of resilience. For cities that have experienced natural or cultural disasters, resilience is held up as a means of recovering. Resilient cities and resilient people are seen as having the attribute of bouncing back from adversity. Again there is an ethical dilemma, as it would be problematic to suggest it would be better for cities to be vulnerable to disaster. Yet it is also unethical to impose ideas of resilience onto the residents of such cities. The presumption that cities and their residents are resilient and coping can have a counter effect in that the pressure to appear resilient masks the indelible and ongoing emotional situation. This situation resonated in Christchurch in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquakes, when residents became tired of hearing how resilient they were, mental health issues were escalating and the physical recovery of the city seemed daunting. For outsiders to refer to those affected by disaster as being resilient can also be a type of deferral, a means of absolving them from the need to provide further assistance.

Balanced against resilience is Karen Till’s framing of cities mired in the aftermath of disaster as “wounded.” Till focuses specifically on cities that have experienced state-perpetrated violence and she points to the concept of a wound as a way of resisting forgetting. This comparison to a wound is a way of allowing for emotion, of recognizing that the city moves us, and accepting that this is part of a more holistic frame of wellbeing that recognizes a place of sadness. For Till, “open wounds in the cities of Kassel and Berlin create an irritation in everyday space through which the past collides with the present. These commemorative sites are ‘out of place’ in the contemporary urban setting, for they are defined by (re)surfacing and repressed memories of violent pasts.”3

Wounds in the city fabric: stumbling stones in Berlin mark the lives of Holocaust victims and where they once lived.

Image: Jacky Bowring

Moving places

Cities are places where we can vividly feel our tininess amid the vastness of our universe. In cities we can embrace what phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard called “intimate immensity,” a melancholic and meditative mode of navigating the world. Becoming attuned to the grain of the city, its traumas, its memories, its nausea, its euphoria, imbues us with emotional richness. How can we capture this as designers? Sometimes it might mean the ultimate in design discipline – doing nothing, or very little. To respond to Juhani Pallasmaa’s critique of contemporary buildings, can we make places that “enter the realm of poetry or … awaken the world of unconscious imagery”? These are places that go beyond mere visual surface effects and embrace “the tragic, the melancholy, the nostalgic, as well as the ecstatic and transcendental tones of the spectrum of emotions.”4 Ultimately, they are places that allow us to be moved by the city.

1. Nigel Thrift, “Intensities of feeling: Towards a spatial politics of affect,” Geografiska Annaler, vol 86 issue 1 series B, 2004, 57–78.

2. Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

3. Karen Till, The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

4. Juhani Pallasmaa, The Architecture of Image: Existential Space in Cinema (Helsinki: Rakennustieto, 2001).

Source

Practice

Published online: 15 Nov 2016

Words:

Jacky Bowring

Images:

Jacky Bowring

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2016