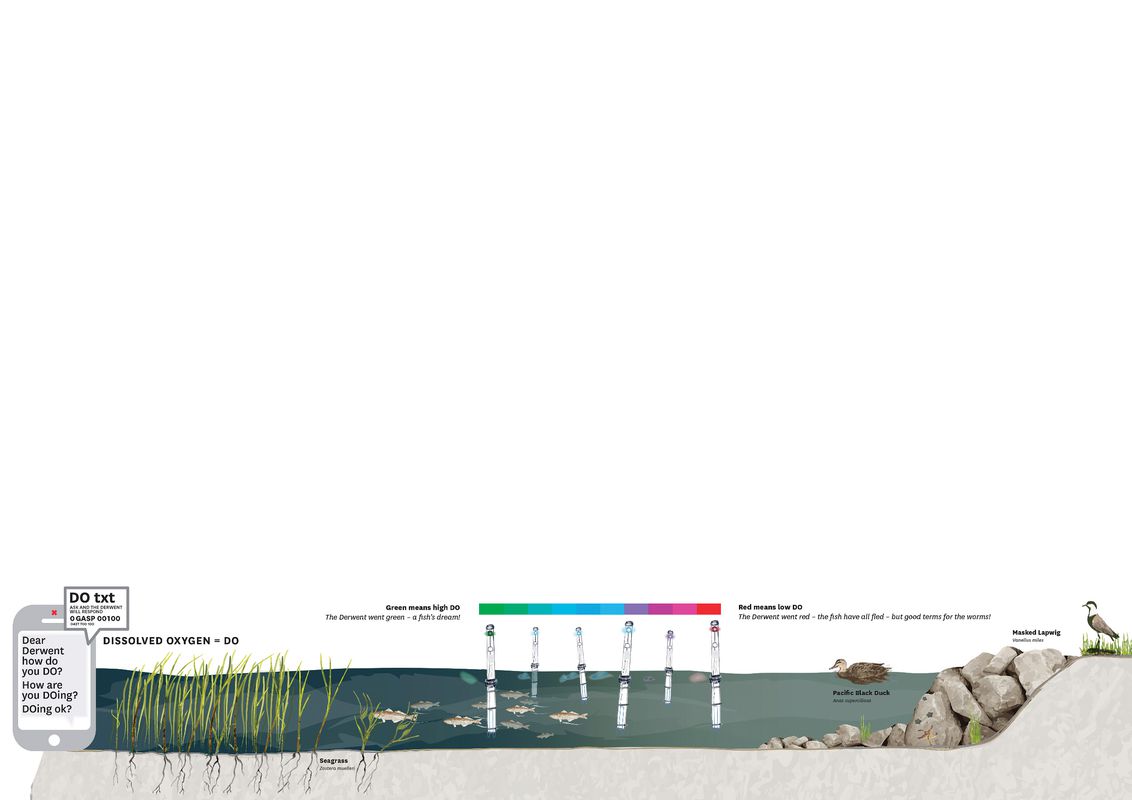

Snow on the mountain, a cold, blustery wind, a choppy, grey River Derwent. And on the water in Hobart’s Elwick Bay, in two parallel lines of sixty metres alongside one of the boardwalks, short transparent poles on blue flotation buoys bob up and down, one or two pulled out of line by the unusually high tide of the previous night. Each of the poles has two lights. One ranges from red to green according to the level of dissolved oxygen in the surrounding water, and the other is white, activated when a text message is sent to the installation and a reply returned. The poles form an installation, Amphibious Architecture, commissioned by GASP! – Glenorchy Art and Sculpture Park – and developed by Queensland-born, New York-based artist, engineer and designer Natalie Jeremijenko.

Amphibious Architecture is an interactive and responsive work. It is also a very delicate intervention and not only because of its susceptibility to the tide – on a grey day like this, the installation could easily be overlooked, and even in more congenial conditions, the installation does not try to impose itself on the river or on the attention of the passer-by. In this respect, Jeremijenko’s work, like GASP itself, stands in stark contrast with David Walsh’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), whose rusted walls look down on the bobbing poles from the headland that forms the northern edge of the bay.

Each of the poles has two lights. One ranges from red to green according to dissolved oxygen levels, and the other is white, activated when a text message is sent to the installation and a reply returned.

Image: Hype TV

Amphibious Architecture is an insinuation into the riparian landscape of the bay – the buoyed poles are at the mercy of the river, but are also designed to connect with and respond to the river’s ecology. In addition, they are intended to connect with the Glenorchy community, drawing them into engagement and, through text messaging, into a “conversation” with the river.

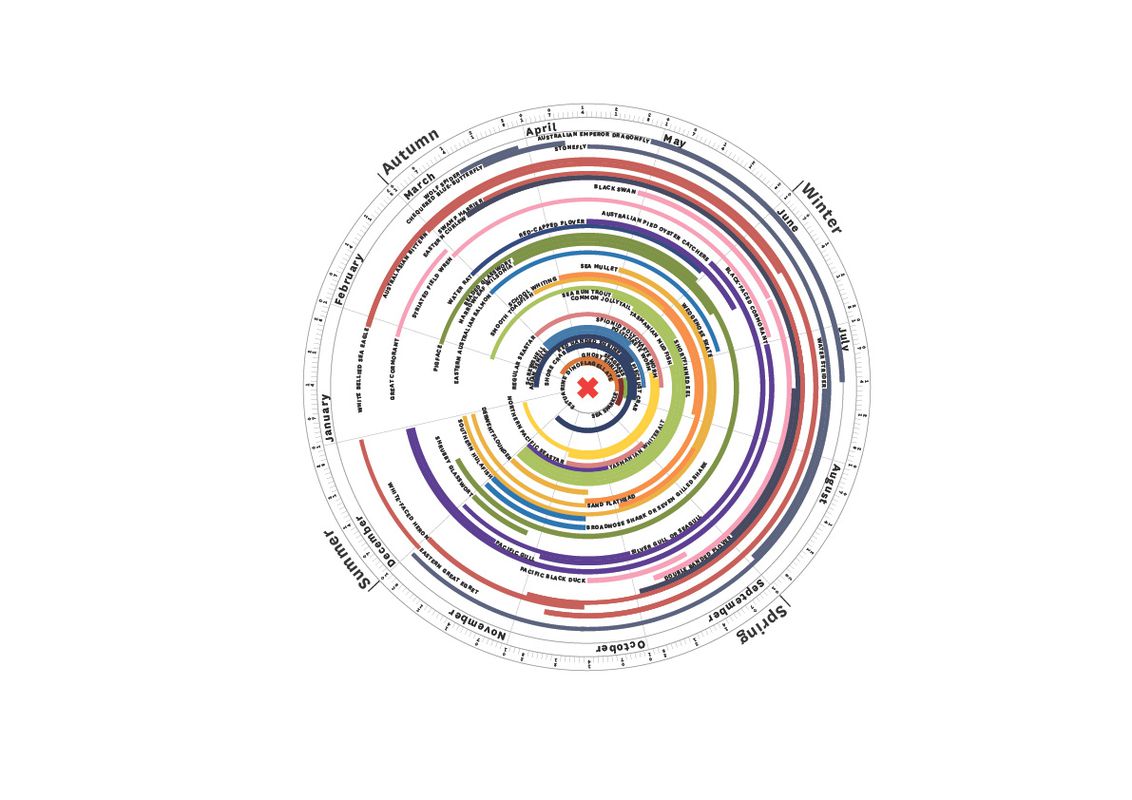

The original prototype for the GASP installation was temporarily installed by Jeremijenko’s Environmental Health Clinic in the Bronx and East Rivers in New York in 2009. Like its prototype, the GASP installation (with a Crown licence for up to ten years) will eventually interact with other aspects of the Derwent’s life – its tethering lines, for instance, are designed to encourage mussel growth. The fact that the installation does not try to elbow its way into our attention may lead some to dismiss it as lacking in impact. Yet in many ways it is not the material installation that comes to the fore here: the bobbing poles are not a statement in themselves, but rather serve to facilitate a connection between the river and the shore, between the water and the land – or more specifically between the water and the human. In this respect, the installation operates as an artwork, not through any direct aesthetic appeal, but by working as an enabler of communication and perhaps even of agency – through its own responsiveness and the responsiveness, and “responsibility,” that it enables and encourages.

The poles indicate the river’s heath by measuring oxygen levels in the water – buoyed thermometers whose red lights are the signal of a fever. Levels of dissolved oxygen depend on water salinity and water temperature, and an increase in either reduces oxygen solubility. A level of dissolved oxygen that is too high or too low can harm aquatic life and affect water quality. Oxygen levels in a river such as the Derwent are markers, not only of water contamination that might undermine the oxygen cycle through the prevention of plant photosynthesis (one source of dissolved oxygen), but also of climate change through increased water temperature. The green and red lights of Jeremijenko’s buoyed poles thus tell us about the river at the same time as they connect us to our own environmental experience; they show us the mutuality that underpins the life of the river and the life in which we are also entangled.

The idea of such mutuality is central to Jeremijenko’s work and is surely one reason she has described herself as “systems designer” more so than “artist” – although the systems she is involved in designing, such as Amphibious Architecture, are themselves secondary to the larger environmental systems with which they aim to connect, into which they aim to provide insight, and on which they also depend. For Jeremijenko, the designing of such systems is not merely about the design of systems aimed at information or education – the larger objective is to shift our conceptions of ourselves and of our environment so as to enable a shift in the kinds and possibilities of agency. In this respect, Jeremijenko’s projects, whether in New York, London, The Hague or Hobart, have an essential optimism about them that also reflects the playful character of those projects. Such playfulness can be seen as part of what is at issue in the very idea of mutuality – in the to-and-fro movement that is part of any responsive system – but in a human setting such playfulness is surely also part of the freeing-up of thinking that is necessary if we are to enable a healthier environment.

For Jeremijenko, then, installations like Amphibious Architecture do not try to preach or to educate, but to involve us (and what better way of doing this than through play), and in involving us to bring us to a recognition that we are already involved. The lightness of touch that marks Jeremijenko’s installation on the Derwent reflects a lightness of tone and mood that is directly connected with the playfulness that is at issue here. Just as her artworks and installations aim to function in ways that improve the environments in which they engage – they are artworks that “work” – so they also aim to provide the stimulus and sometimes the means to enable individuals and communities to make their own environmental circumstances better. Perhaps this is part of the reason why Jeremijenko’s work has been so successful, although it may also be why it has sometimes attracted criticism from other parts of the environmental movement. Unobtrusive though it might seem, Amphibious Architecture at GASP nevertheless deserves our attention, all the more so inasmuch as it provides a point of entry into the work of an enormously talented and prolific designer and artist.

Credits

- Project

- Amphibious Architecture – What Does the Derwent Want?

- Design practice

-

Natalie Jeremijenko (Environmental Health Clinic, New York University, The Living Architecture Lab at Columbia University)

- Project Team

- Natalie Jeremijenko, Pippa Dickson, Sarah Jones

- Consultants

-

Bathymetry

Marine Solutions

Communications Telstra

Dissolved Oxygen Tests Joe Adelstein, Tassal

Engineer Burbury Consulting

Environmental consultant Aquenal, Derwent Estuary Program, Tassal, IMAS at University of Tasmania

Install team Subsea Access

Lights Julian A. McDermott Corp.

Marine Instrumentation and programming Imbros

Prototyping Adrian Oliver

Site electrical Ilec

- Site Details

-

Location

Hobart,

Tas,

Australia

Site type Coastal

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 18 months

Construction 6 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Conservation, Installations

- Client

-

Client name

Glenorchy Art and Sculpture Park

Website gasp.org.au

Source

Review

Published online: 9 Jan 2017

Words:

Jeff Malpas

Images:

Environmental Health Clinic.,

Hype TV,

Katie Hepper and Tracey Allen

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2016