J R. R. Tolkien’s war-torn, lifeless land of Mordor made a stark contrast to his fertile, pastoral Shire. At the end of The Lord of the Rings , even the Shire is affected by the war. Sam has to use all his skills to heal and restore its landscape. Peter Jackson didn’t include this final aspect in the films he directed, but it seemed a fitting conclusion, the damage to home finally healed by a Middle-earth version of a landscape architect.

Of course there are similarities between this novel and the troubles of Europe in the world wars. Tolkien famously said, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations,” but he must have been profoundly influenced by both wars. When he started writing The Lord of the Rings in 1937, only nineteen years had passed since the end of the Great War, in which he had served. It took him until 1949 to finish The Return of the King , the last book in the trilogy. The passages in Mordor and the last “Scouring of the Shire” chapters would have been written with knowledge of the reality of the UK’s bombed towns such as Coventry, Glasgow and London. The hobbits’ desire for a homely, pastoral life after their trials would have reflected the desire of many soldiers of the world wars to escape the awful, blasted terrains of Europe and Asia and retreat to the familiar landscapes of their home countries.

This restorative quality of the landscape is a powerful thing. The Victorians used it as an integral part of the healing process in the hospitals of the nineteenth century. Gardens and landscape were the structuring elements of the garden cities and workers’ villages created in the late nineteenth century, built to provide relief from the industrial grind. Frederick Law Olmsted and Joseph Paxton, two great nineteenth-century landscape architects, developed this idea and did wonders for the civilizing of the industrial revolution’s unhealthy environments. They created parks and more liveable towns so that workers and residents could escape the drudgery and experience nature around them. Olmsted died at the beginning of the twentieth century, before the Great War, but his legacy continued through his work and influenced landscape architecture and city shaping throughout the twentieth century, for example Walter Burley Griffin’s designs for Canberra.

Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

Image: Gareth Collins

The call-ups of troops for the Great War and the Second World War temporarily stalled the development of landscape architecture and civic design in general. In Australia, for example, during the Great War, plans for Canberra were slowed and reviewed to save costs.

In the Second World War, it was a different story with the aggressors. Hitler had an interest in architecture and continued to commission designs for grand new places and cities well into the war. Albert Speer was his favoured architect, at least initially, and the relationship between the two of them is fascinating. But for the Allies, dreams were of freedom, not designing cities. Defence of their nations was the primary focus. My grandfather, for example, gave up his hopes of becoming an architect to enter the merchant navy in the Second World War. It was a six-year task, after which the imperative to earn money quickly took him into sign-writing, not the study of architecture.

The imperative in 1945 wasn’t necessarily good design. But a few visionaries saw a longer-term requirement for places that people could thrive in, with green space, well-laid-out housing, roads, trees and parks. Examples include Ian McHarg (1920–2001), who studied landscape architecture at Harvard University after serving in Italy in the Parachute Regiment. He returned to his home town of Glasgow to help rebuild the city. Dame Sylvia Crowe (1901–1997) lived through both world wars. She was involved in the design of the new towns of the UK in the 1950s and 60s. Lawrence Halprin (1916–2009) served in the Pacific, returning to the US after surviving a kamikaze attack to pursue landscape architecture. Peter Spooner (1919–2014) helped establish landscape architecture as an academic pursuit in Australia, also after serving in the war.

The large investment in city rebuilding in Europe and the war-related prosperity of the USA spawned an expanding landscape design industry. Government and the private sector needed landscape architects. Colleges and universities throughout the world took up the challenge of providing them. In Australia Spooner established a course at the University of New South Wales in 1964. In America, McHarg established a masters course at the University of Pennsylvania in 1954. In the UK, Frank H. Clark (1902–1971), the chief landscape architect for the 1951 Festival of Britain, started lecturing in landscape architecture at the Edinburgh College of Art in 1959, establishing a course in 1962.

M1 motorway, Sydney to Newcastle.

Image: Courtesy of Roads and Maritime Services

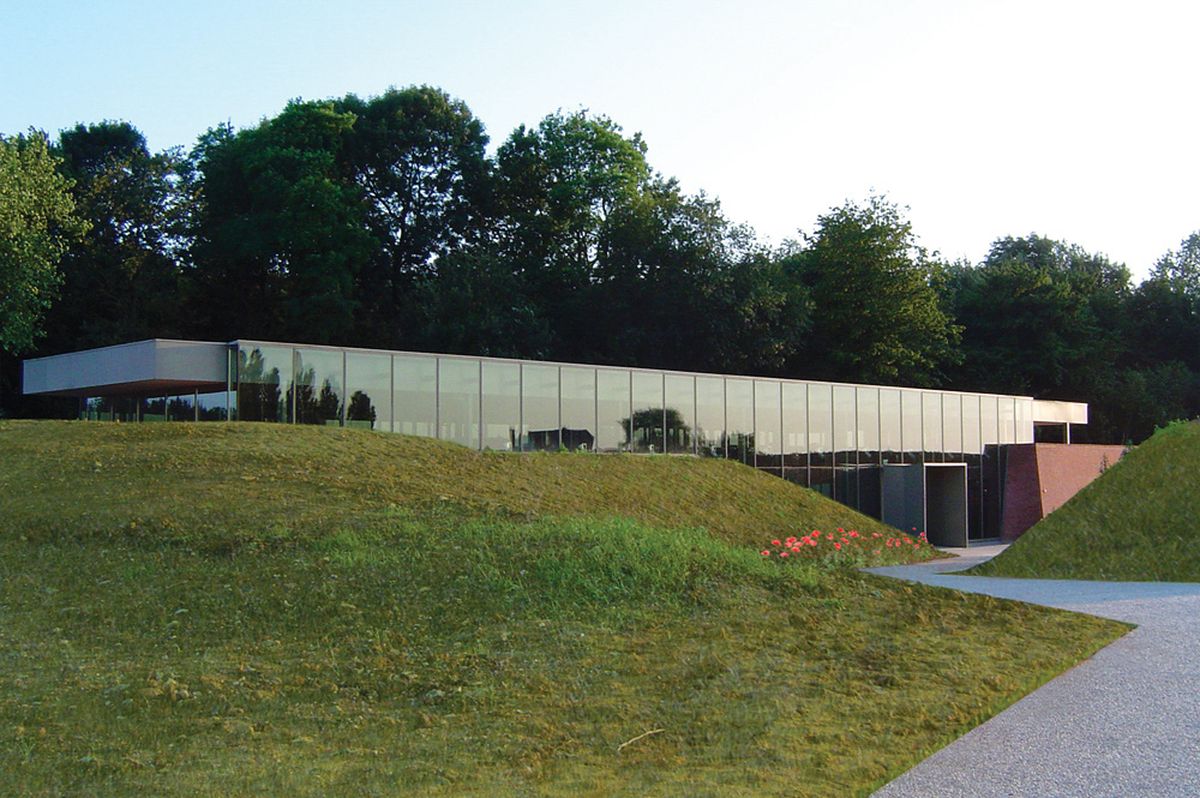

An important need for landscape architecture stemming from the world wars has been the design of places in remembrance of the fallen. The cemeteries and visitor areas in France and Belgium have their own landscape character and a powerful sense of place. At Thiepval, a village totally destroyed in the Great War, the 1932 Edwin Lutyens-designed memorial, the largest British war memorial in the world, is the dominant element. Nearby, however, is the visitor centre (opened 2004), prostrate and humble in the land form, the glass walls reflecting sky, trees and meadows.

Like Thiepval, the more successful war memorials are often integrated with their landscape settings, providing natural, spiritual environments. The Australian War Memorial in Canberra, designed by Emil Soderston and John Crust, is an important exemplar. Set against the rugged Australian bushland, the memorial fits into the broad vistas and avenues laid out by Walter Burley Griffin. Remembrance Driveway, which runs between Macquarie Place in Sydney and the war memorial in Canberra, is a living memorial of trees. Supported by landscape architects, the Remembrance Driveway Committee is now sixty years old. It oversees the planning, design and maintenance of groves and avenues of trees on the Hume and Federal Highways.

In some respects the profession of landscape architecture has been matured by the wars. It now has a firmly developed role in helping shape our environment, influencing, among many other things, road infrastructure design. After the Second World War road infrastructure was seen as vital to the development of economies that had suffered in the war and also vital to the defence of nations. A legacy of this is the height of road bridges, set at 5.3 metres – enough room for a tank transporter to pass under.

Crowe and Halprin (among others) wrote about road design in their books The Landscape of Roads (1960) and Freeways (1966) respectively. Spooner’s important work in the shaping of the freeway between Sydney and Newcastle in the 1960s helped establish landscape architecture as a mainstream activity within the NSW Roads and Maritime Services state authority, as set down in “Beyond the Pavement: Urban Design Policy Procedures and Design Principles.”

We are now in the hundredth year since the beginning of the Great War. As landscape architects it is worth reflecting on the legacy of both that war and the ensuing Second World War. Despite the great tragedy of these events, both wars had a profound effect on landscape architecture and on the growth and value of the profession to society in healing and restoring, revitalizing and remembering.

Source

Practice

Published online: 8 Apr 2016

Words:

Gareth Collins

Images:

Courtesy of PLAN.01,

Courtesy of Roads and Maritime Services,

Gareth Collins,

Greg Jackson

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, November 2014